Veterinary Advice Online: Spaying Cats.

Feline

spaying (cat spay procedure) - otherwise known as spaying cats, female neutering, sterilisation, "fixing", desexing, ovary and uterine ablation, uterus removal or by the medical term:

ovariohysterectomy - is the surgical removal of a female cat's ovaries and uterus for the purposes of feline population control, medical health benefit, genetic-disease control and behavioral modification. Considered to be a basic component of responsible

female cat ownership, the spaying of female cats is a simple and common surgical procedure that is performed by veterinary clinics all over the world. This page contains everything you, the pet owner, need to know about spaying cats (

female cat desexing). Cat spay topics are covered in the following order:

1. What is spaying?

2. Feline spaying pros and cons - the reasons for and against spaying cats.

2a. The benefits of feline spaying (the pros of spaying cats) - why we spay cats.

2b. The disadvantages of desexing (the cons of spaying cats) - why some people choose not to spay their female cats.

3. Information about cat spaying age: when to spay a cat.

3a. Current desexing age recommendations.

3b. Spaying kittens - information about the early spay and neuter of young cats (kitten desexing).

4. Cat spaying procedure (spay operation) - a step by step pictorial guide to feline spay surgery.

5. Spaying After Care - all you need to know about caring for your female cat after spaying surgery. Includes information on feeding, bathing, exercising, wound care, pain relief and stopping cats from licking surgical wounds.

6. Spay Complications - Possible surgical and post-surgical (post-op) complications and problems of spaying cats.

6a. Pain after surgery (e.g. cat walking stiffly, not wanting to sit down and so on).

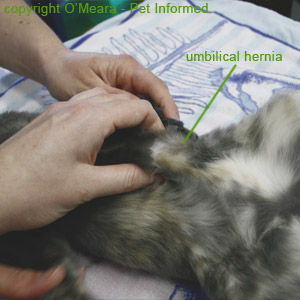

6b. A large 'lump' or 'swelling' at the spay operation site (hernias and seromas).

6c. Wound break-down - partial or complete break down of the skin stitches.

6d. Wound infection.

6e. Suture-site reactions - swollen, red skin around sutures or stitches.

6f. Excessive wound hemorrhage (excessive bleeding during or after surgery).

6g. Failure to ligate (tie off) the ovarian or uterine (uterus) blood vessels adequately.

6h. Peritonitis.

6i. Ureter laceration.

6j. Post-operative renal failure (kidney failure).

6k. Anaesthetic death.

6l. Tracheal damage in cats caused by the over-inflation of ET (endotracheal) tubes.

7. Late complications or problems associated with spaying female cats.

7a. Weight gain.

7b. Ovarian remnants (incomplete feline spay) - the cat comes back into heat after spaying.

7c. Lactation and mammary (breast) enlargement after feline spaying.

8. Frequently asked questions (FAQs) and myths about spaying felines:

8a. Myth 1 - All desexed queens gain weight (get fat).

8b. Myth 2 - Without her reproductive organs, a female cat (queen) won't feel like "a woman".

8c. Myth 3 - Female cats need to have sex before being desexed.

8d. Myth 4 - Female cats should be allowed to give birth to a litter before being spayed.

8e. Myth 5 - Vets just advise neutering for the money not for my cat's health.

8f. FAQ 1 - Why won't my veterinarian clean my cat's teeth at the same time as spaying her?

8g. FAQ 2 - Why shouldn't my vet vaccinate my cat whilst she is under anaesthetic?

8h. FAQ 3 - Can my cat be spayed whilst she is in heat?

8i. FAQ 4 - Spaying a pregnant cat - can my pregnant cat be spayed?

8j. FAQ 5 - My pregnant cat needed a caesarean (C-section) - can she be spayed at the same time?

8k. FAQ 6 - Will spaying make my cat incontinent?

8l. FAQ 7 - Is spaying safe? It's just a routine procedure isn't it?

8m. FAQ 8 - My veterinarian offered a pre-anaesthetic blood screening test - is this necessary?

8n. FAQ 9 - When is feline spaying surgery high-risk or not safe to perform?

9. The cost (price) of spaying:

9a. The typical cost of spaying a female cat at a veterinary clinic.

9b. Where and how to source low cost and discount feline spaying.

9c. Free feline spaying.

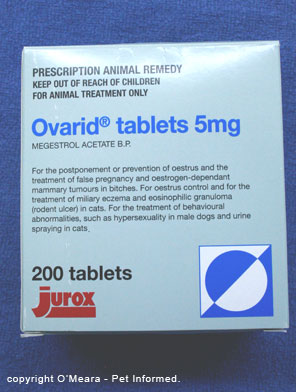

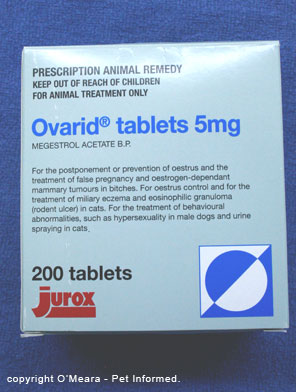

10. Alternatives to spaying your female cat:

10a. Feline birth control method 1 - separate the tom from the queen and prevent her from roaming.

10b. Feline birth control method 2 - neuter your male cat and keep your female cat inside.

10c. Feline birth control method 3 - "the pill" and hormonal female oestrous (heat) suppression.

10d. Feline birth control method 4 - inducing ovulation to suppress feline estrus (heat).

WARNING - IN THE INTERESTS OF PROVIDING YOU WITH COMPLETE AND DETAILED INFORMATION, THIS SITE DOES CONTAIN MEDICAL AND SURGICAL IMAGES THAT MAY DISTURB SENSITIVE READERS.

1. What is spaying?

1. What is spaying?

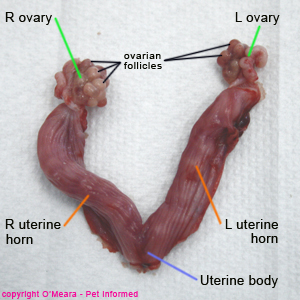

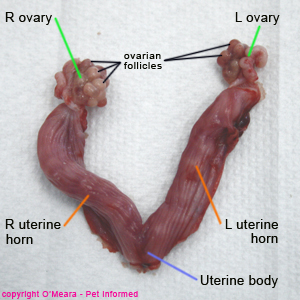

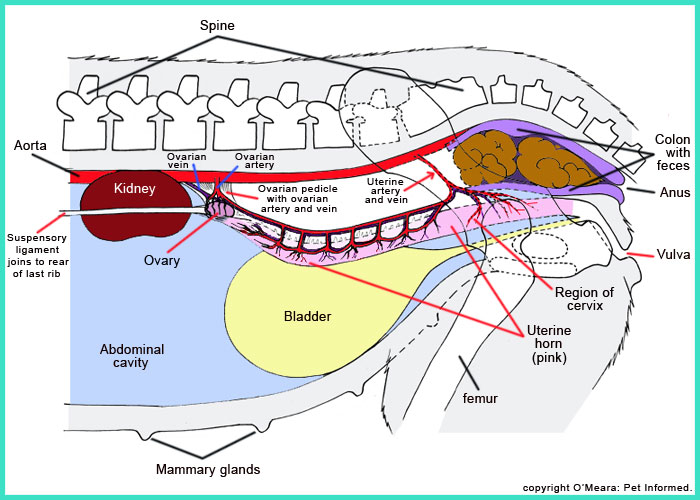

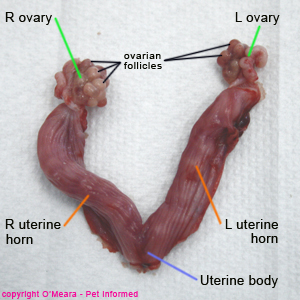

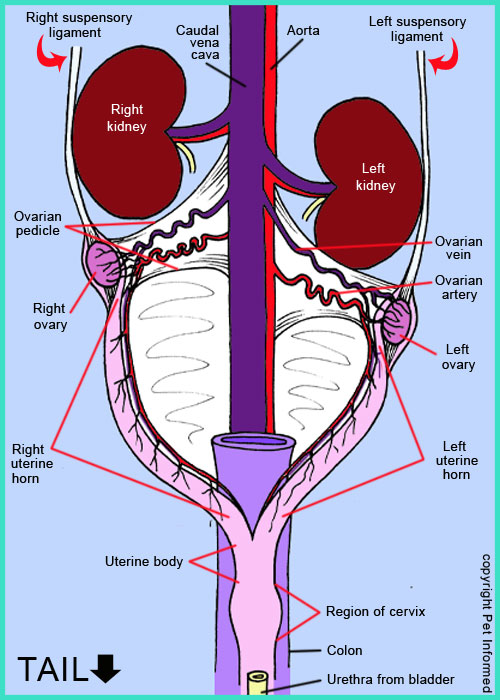

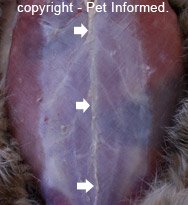

Spaying or desexing is the surgical removal of a female (queen) cat's internal reproductive structures including her ovaries (the site of ova/egg production), Fallopian tubes, uterine horns (the two long tubes of uterus where the fetal kittens develop and grow) and a section of her uterine body (the part of the uterus where the uterine horns merge and become one body). The picture on the right shows a cat uterus that has been removed by cat spaying surgery - it is labeled to give you a clear illustration of the reproductive structures that are removed during surgery.

Spaying or desexing is the surgical removal of a female (queen) cat's internal reproductive structures including her ovaries (the site of ova/egg production), Fallopian tubes, uterine horns (the two long tubes of uterus where the fetal kittens develop and grow) and a section of her uterine body (the part of the uterus where the uterine horns merge and become one body). The picture on the right shows a cat uterus that has been removed by cat spaying surgery - it is labeled to give you a clear illustration of the reproductive structures that are removed during surgery.

Basically, the parts of the female reproductive tract that get removed are those which are responsible for egg (ova) production, embryo and fetus development and the secretion of the major female reproductive hormones (oestrogen and progesterone being the main female reproductive hormones). Removal of these structures plays a huge role in feline population control (without eggs, the female cat can not produce young; without a uterus, there is nowhere for the unborn kittens to develop); feline genetic disease control (female cats with genetic disorders can not pass on their inheritable disease conditions to any young if they can not breed); the prevention and/or treatment of various medical disorders (spaying prevents and/or treats a number of ovarian and uterine diseases as well as various hormone-enhanced medical conditions)

and female cat behavioral modification (e.g. estrogen is responsible for many female cat behavioral traits that some owners find problematic - e.g. roaming, calling for males - and spaying, by removing the ovarian source of female hormones, may help to resolve these issues).

2. Feline spaying pros and cons - the reasons for and against spaying cats.

2a. The benefits of spaying cats (the pros of spaying) - why we spay female cats.

There are many reasons why veterinarians and pet advocacy groups recommend the desexing of

entire female cats. Many of these reasons are listed below, however the list is by

no means exhaustive.

1. The prevention of unwanted litters:

Pet overpopulation and the dumping of unwanted litters of kittens (and puppies) is an

all-too-common side effect of irresponsible pet ownership. Every year, thousands of unwanted kittens and older cats are surrendered to shelters and pounds for rehoming or dumped on the street (street-dumped animals ultimately end up dying from starvation, predation or transmissible

feline diseases or finding their way into pounds and shelters that may or may not be

able to find homes for them). Many of these animals do not ever get adopted from the pounds and shelters that take them in and most end up being euthanased. This sad waste of healthy life can be reduced by not letting pet cats breed indiscriminately and the best way of preventing any accidental, unwanted breeding from occurring is through the routine neutering of all non-stud (non-breeder) female cats (and male cats too, but this is another page).

Pet overpopulation and the dumping of unwanted litters of kittens (and puppies) is an

all-too-common side effect of irresponsible pet ownership. Every year, thousands of unwanted kittens and older cats are surrendered to shelters and pounds for rehoming or dumped on the street (street-dumped animals ultimately end up dying from starvation, predation or transmissible

feline diseases or finding their way into pounds and shelters that may or may not be

able to find homes for them). Many of these animals do not ever get adopted from the pounds and shelters that take them in and most end up being euthanased. This sad waste of healthy life can be reduced by not letting pet cats breed indiscriminately and the best way of preventing any accidental, unwanted breeding from occurring is through the routine neutering of all non-stud (non-breeder) female cats (and male cats too, but this is another page).

Author's note: The deliberate breeding of family pets should never be considered an

easy way to make a quick buck. A lot of cost and effort and expertise goes into producing a quality litter of kittens for profitable sale. And that's only if nothing goes wrong! If your queen

needs a caesarean section at one in the morning or develops a severe infection after queening (e.g. pyometron, mastitis), then all of your much planned profits will rapidly turn into financial losses (the vet fees for these kinds of treatments are high). On top of that, if you fail to do your homework and you breed poor quality kittens or poorly socialized

kitties that won't sell, then you've just condemned some of those young animals to a miserable

life of being dumped in shelters or on the streets.

2. The reduction of stray and feral cat populations:

By having companion cats spayed at young ages, they are unable to become pregnant. This results in fewer litters of unwanted kittens being born

which, in return, benefits not just those unwanted kittens (dumped or shelter-surrendered

kittens can often lead a tough, neglected life), but also society and the environment in general. A proportion of the unwanted kittens that are dumped into the environment do survive and grow up to become feral cats, which in turn reproduce to produce more feral cats. Feral and stray cat populations pose a significant risk of predation to native wildlife (see image opposite); they carry diseases that may affect humans (e.g. rabies, worms) and their pets (e.g. rabies, FIV, FIA, FeLV, parasites); they fight with domestic pets inflicting nasty cat-fight wounds and abscesses; they steal the food of domestic pets and they place a huge financial and emotional burden on the

pounds, shelters and animal rescue groups which have to deal with them.

By having companion cats spayed at young ages, they are unable to become pregnant. This results in fewer litters of unwanted kittens being born

which, in return, benefits not just those unwanted kittens (dumped or shelter-surrendered

kittens can often lead a tough, neglected life), but also society and the environment in general. A proportion of the unwanted kittens that are dumped into the environment do survive and grow up to become feral cats, which in turn reproduce to produce more feral cats. Feral and stray cat populations pose a significant risk of predation to native wildlife (see image opposite); they carry diseases that may affect humans (e.g. rabies, worms) and their pets (e.g. rabies, FIV, FIA, FeLV, parasites); they fight with domestic pets inflicting nasty cat-fight wounds and abscesses; they steal the food of domestic pets and they place a huge financial and emotional burden on the

pounds, shelters and animal rescue groups which have to deal with them.

3. To reduce the spread of inferior genetic traits, genetic diseases and congenital deformities:

Cat breeding is not merely the production of kittens, it is the transferral of genes and genetic traits from one generation to the next in a breed population. Pet

owners and breeders should desex female cats that have conformational, coloring and temperamental traits,

which are unfavourable or faulty to the breed as a whole, to reduce the spread of these

defects further down the generations. Female cats with heritable genetic diseases and

congenital defects/deformities should also be desexed to reduce the spread of these

genetic diseases to their offspring.

Some examples of proven-heritable or suspect-heritable diseases that we select against

when choosing to spay cats include: polycystic kidney disease (PKD),

lysosomal storage diseases and amyloidosis. There are many others.

Picture: This is a close up image of the vulva of a bitch (?) with hermaphrodism (canine hermaphrodite). Her clitoris is massively enlarged, forming a miniature penis that protrudes from the vulva.

Animals with hermaphrodism are of poor breeding quality (they are often, but not always, infertile)

and many may even have significant sex-chromosome defects (e.g. XX/XY chimeras). These animals should be desexed and not bred from.

4. The prevention and/or treatment of ovarian and uterine diseases:

It is difficult to contract an ovarian or uterine disease if you have no ovaries or uterus. Early spaying prevents female cats from contracting a range of ovarian and uterine diseases and disorders including: uterine cancer, ovarian cancer, polycystic ovaries, metritis or endometritis (severe uterine or uterine wall inflammation, often with bacterial infection, usually seen after whelping), mucometra (a uterus full of glandular mucus), cystic endometrial hyperplasia (large cysts in the wall of the uterus

that predispose cats to pyometra), pyometra or pyometron (infection and abscessation of the uterus that is similar to metritis and endometritis, but not usually associated with pregnancy and whelping), ectopic pregnancy (pregnancy outside of the uterus), uterine prolapse and uterine torsion.

Image 1: This is an ultrasound image of a large ovarian cancer (4-5cm in diameter) that was taken from a 5kg dog. The black spaces/holes that you can see throughout the mass are mutated 'ovarian follicles' (fluid-filled cystic

structures akin to those "true ovarian follicles" which produce the ova/eggs in a normally-functioning ovary) that the cancerous ovarian follicular cells have produced in an attempt to mimic their normal function within the ovary.

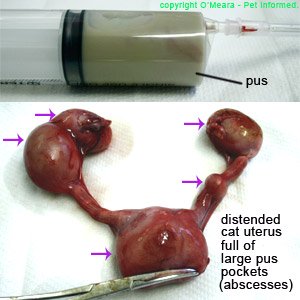

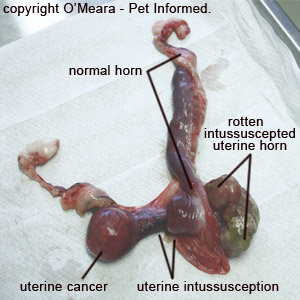

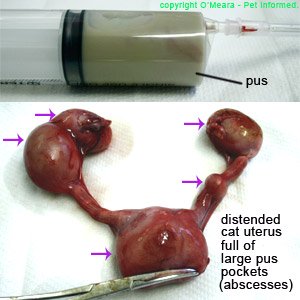

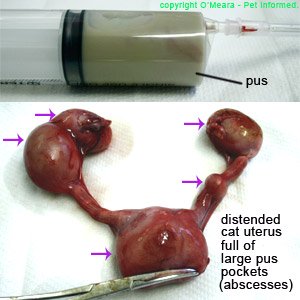

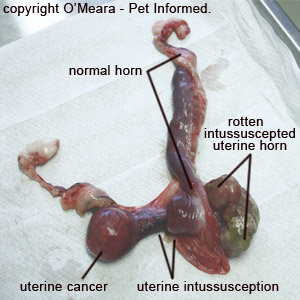

Image 2: This an image of an abnormal cat uterus that was removed by feline spaying surgery. The uterus

is full of abscess pockets (infection and pus) - a classic case of feline pyometra. The purple arrows

point to individual abscesses within the uterus. The syringe in the image contains pus, which was drawn from the uterus by needle.

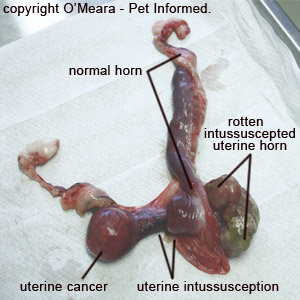

Image 3: This is a rabbit uterus with two major problems, both of which could have been prevented

by early rabbit spaying surgery. The uterus contains a large (2cm diam) uterine cancer. It also contains

a uterine intussusception. A uterine intussusception is a condition whereby one section of uterine horn telescopes into another section of the uterine horn. The telescoped uterine horn becomes strangled inside the other section of uterine horn (as seen in this image), causing it to die and rot and become necrotic (decaying tissue). You can see the dead telescoped section of uterus in this image - it is green in color and gangrenous.

5. The prevention or reduction of hormone-induced diseases:

The dog situation:

It is well known that entire female dogs do suffer from a range of diseases and medical conditions that are directly associated with high blood estrogen and/or progesterone levels (the hormones produced by the ovaries). These conditions include: vaginal hyperplasia (a large swelling of the roof of the vaginal passage, which results in a large red or pink ball of flesh protruding from the bitch's vulva - see image below); mammary neoplasia (breast cancer in dogs is greatly influenced by hormones and bitches spayed prior to their first season

almost never develop the condition); mammary enlargement; cystic endometrial hyperplasia; pyometron

(the development of uterine conditions favorable to the development of pyometra is greatly reliant on

seasonal ovarian reproductive hormone fluctuations); pseudopregnancy (false pregnancy or phantom pregnancy with accompanied signs of 'expecting' including nesting behaviours, abdominal enlargement, breast enlargement and even lactation) and certain desexing-responsive skin disorders (e.g. estrogen-induced dermatoses).

Some entire bitches develop follicular cysts on their ovaries (also termed polycystic ovaries - ovaries with too many actively-secreting ovarian follicles), which produce excessive amounts of oestrogen, well above the quantities usually

seen in a normal entire bitch. This can result in a number of estrogen-induced behavioral problems

manifesting (e.g. nymphomania, excessive libido, mounting toys) as well as a range of potentially

life-threatening medical problems associated with oestrogen toxicity including: bone marrow suppression (complete failure of production of red blood cells, white blood cells and platelets), blackening of the skin (hyperpigmentation), hairloss or poor coat quality and abnormally increased mammary development.

High levels of ovary-derived reproductive hormones (e.g. progesterone) can also interfere with the management of

other medical conditions. Diabetes mellitus is a good example of this. Progesterone inhibits the action of insulin on

the body cells' insulin receptors, producing a condition called 'insulin resistance' and Type 2 diabetes (similar to parturient diabetes or 'pregnancy diabetes' seen in women). What happens is that insulin (e.g. Caninsulin, Actrapid and others) given to the pet to manage its diabetes does not work as effectively in the presence of progesterone. This can make the animal's diabetes very difficult to control every time it has a season and it is one of the main reasons why vets recommend the desexing of diabetic dogs as part of the management of the disease. Other diseases whose severity or management can be adversely affected by high reproductive hormone levels include acromegaly, epilepsy, cushings disease (hyperadrenocorticism) and generalised Demodex mites.

Desexing removes the main source of oestrogen and progesterone from the animal's body (the ovaries), which not only prevents the onset of these diseases or conditions, but can even help to control or manage these diseases if they are already present.

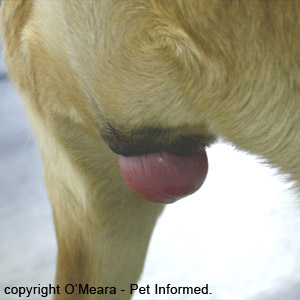

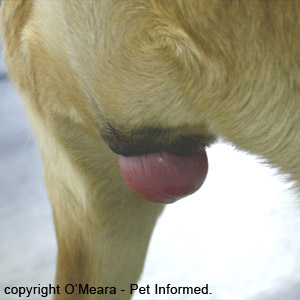

Photograph: This is an image of the vulva of a bitch with vaginal hyperplasia, also called vaginal prolapse

(some people, incorrectly, term this condition uterine prolapse, however, uterine prolapse is

a different condition altogether). The red or pink swelling protruding from the vulval opening is

the roof of the dog's vagina. This condition is hormonal and can often be resolved through spaying.

The cat situation:

Female cats do not seem to suffer as much from the huge range of reproductive-hormone-associated diseases and medical conditions that have just been described in the dog. This is probably

because this species cycles almost continuously all year round (as opposed to the bitch who only cycles

once to twice a year) and has thus developed a much greater tolerance towards its own reproductive

hormone fluctuations than the dog. Diseases such as vaginal hyperplasia, mammary neoplasia, cystic endometrial hyperplasia

and pyometron are much less common in the cat than the dog.

This reduced incidence of hormonally-associated disease is, however, no excuse not

to get this species desexed. Although not as commonly seen in the cat as in the dog, cats do still

get mammary tumors, the development of which is likely to be affected by the presence of

ovarian reproductive hormones. Similar to the situation described in the dog, early desexing of cats may have some protective effect in preventing the development of mammary cancers in cats. Note - one reference (23) suggested that the breast-cancer-preventative effect of desexing in cats was not quite as strong as the preventative effect seen in dogs, however, another reference (2) suggested that it was greatly preventative. I would err on the side of caution and have the animal desexed early in case there is value in having the procedure done. For mammary cancer is a condition that cat owners should seek to minimize where possible - the vast majority of mammary cancers

in the cat are very nasty (>80% are malignant and have the potential to spread throughout the cat's body, resulting in death). Similarly, although not as common in the cat as in the dog, cystic endometrial hyperplasia and pyometron are also hormonally-induced diseases that can be encountered in the cat,

potentially resulting in life-threatening illness.

As mentioned in the dog section, high levels of ovary-derived reproductive hormones (e.g. progesterone) can also interfere with the management of

other medical conditions. Diabetes mellitus is a good example of this. Progesterone inhibits the action of insulin on

the body cells' insulin receptors, producing a condition called 'insulin resistance' and Type 2 diabetes (similar to parturient diabetes or 'pregnancy diabetes' seen in women). What happens is that insulin (e.g. Caninsulin, Actrapid and others) given to the pet to manage its diabetes does not work as effectively in the presence of progesterone. This can make the animal's diabetes very difficult to control every time it has a season and it is one of the main reasons why vets recommend the desexing of diabetic cats as part of the management of the disease. Other diseases whose severity or management can be adversely affected by high reproductive hormone levels include acromegaly, epilepsy and feline cushings disease (hyperadrenocorticism).

Desexing removes the main source of oestrogen and progesterone from the animal's body (the ovaries), which not only prevents the onset of these diseases or conditions, but can even help to control or manage these diseases if they are already present.

6. The prevention or reduction of hormone-mediated behavioural problems:

The ovaries are responsible for producing estrogen and progesterone: the hormones that make female animals look and act like female animals. It is the ovaries that make female cats

exhibit the kinds of "female" hormone-dependent behaviors normally attributed to the entire animal. Entire female cats are more likely to exhibit sexualised behaviors including: calling for males, aroused interest males of their own species; nymphomania

(excessive sexual and mating drive) and excessive affection for their owners (in-heat cats

often drive their owners nuts by constantly putting their bottoms in their owners' faces

and yowling at and rubbing up against them). In-heat queens calling for mates can often

seem to be 'in so much pain' (they are extremely restless, they wail, they roll around on their sides and backs ...) that inexperienced owners will sometimes think they are sick or injured! Cats coming

into season can also be moody and unpredictable (PMS?) and they may bite and scratch

owners and other household pets who get too close to them or touch them on the rump. Some of the more dominant cycling females will even display unwanted dominance and territorial behaviors such the marking of territory with urine (although much more commonly exhibited by entire

tomcats, some dominant females will also exhibit urine spraying in the house). Additionally, entire, in-heat female cats are more likely than neutered animals are

to leave their yards and roam the countryside looking for males and trouble. Roaming is a troublesome habit because it puts other animals (wildlife and other pets) and humans at risk of harm from your feline pet and it puts the roaming pet at risk from all manner of dangers including: predation by other animals, attacks by other cats, cruelty by humans, poisoning, envenomation (e.g. snake bite) and motor vehicle strikes. The spaying of entire female cats may help to reduce some of these problematic hormone-mediated behaviours.

Author's note: Fighting between cats is more common when cats are left entire

and undesexed. Although fighting is much more common between entire male cats, fighting can

also occur between male and female cats when a male attempts to mate with a female who

is not yet receptive to his advances. This can result in the female cat attacking the male and

receiving wounds in return. Owners of fighting cats often spend many hundreds of dollars treating their

pets for fight wounds and cat-fight abscesses. Animals that fight are also more likely to

contract the deadly feline AIDS virus (FIV - feline immunodeficiency virus), which is predominantly spread between cats through warring activities (biting and scratching).

By reducing their attractiveness to tomcats, spaying reduces the incidence

of fighting and its secondary complications (clawed and lacerated eyes, cat-fight abscesses, FIV-spread and so on).

7. The reduction of tom cat attraction:

When a female cat comes into heat, she releases pheromones and hormones in her urine that

notify male cats of her increased fertility. At the peak of her cycle, she will also

call and wail, notifying males of her desire to mate. For these reasons, it is not uncommon

for the owners of undesexed female cats to have tom cats constantly coming into their yards

at all times of the day and night.

This is a problem for many reasons. Firstly, the wandering toms will

fight amongst themselves and wail back to the female from outside, thereby producing a lot of ruckus in the

middle of the night. Secondly, the toms will fight with the house owner's cats, resulting in costly cat fight

abscesses and the spread of diseases. Third, the toms will void urine and faeces in the female-cat owner's yard, which kills the plants and grass and leaves behind a pungent and noxious odor. Sometimes, the tomcats will even venture into the female-cat owner's house (they certainly will if there is a cat flap), where they will steal food and mate with the in-heat female in question. If the female cat does escape the house, she is almost certain to be mated and to fall pregnant.

By spaying all of the female cats in your household, there will be nothing to attract

the tom cats into your yard and, consequently, the problem of trespassing tomcats will

be solved.

2b. The disadvantages of desexing (the cons of desexing) - why some choose not to spay female cats.

There are many reasons why some individuals, breeders and pet groups choose not to advocate

the sterilization of entire female cats. Many of these reasons have been listed below, however the list is by

no means exhaustive.

1. The cat may become overweight or obese:

Studies have shown that spayed and neutered animals probably require around 25% fewer calories

to maintain a healthy bodyweight than entire female animals do. This is because a neutered animal

has a lower metabolic rate than an entire animal does (it therefore needs fewer calories to maintain its bodyweight). Because of this, what tends to happen is that most owners, unaware of this fact, continue to feed their spayed cats the same amount of food calories after the surgery that they did prior to the surgery, with the result

that their feline pets become fat. Consequently, the myth of automatic post-desexing obesity has become perpetuated

and, as a result, many owners simply will not consider desexing their cats because

of the fear of them gaining weight and developing weight-related problems (e.g. diabetes mellitus).

Author's note: The fact of the matter is that cats will not become obese simply because they have been desexed. They will only become obese if the post-neutering drop in their metabolic rate

is not taken into account and they are fed the same amount of food calories as an entire animal.

Author's note: Those of you who care about your finances might even be able to see the benefits of desexing here. A spayed cat potentially costs less to feed than an entire animal

of the same weight and, therefore, neutering your animal may well save you money

in the long run.

2. Desexing equates to a loss of breeding potential and valuable genetics:

There is no denying this. If a dog or cat or horse or other animal is the 'last of its line' (i.e. the last kitten in a long line of pedigree breeding cats), a breeder or pet owner's choice to desex that animal and, therefore, not pass on its valuable breed genetics will essentially spell the end for that breeding lineage.

Author's opinion point: of all the reasons given here that argue against the desexing of female cats, this is probably the only one that has any real merit. Desexing does equate to a loss of breeding potential. In an era where many unscrupulous breeders

and pet owners ("backyard breeders" we call them) will breed any low-quality cat, regardless of

breed traits and temperament, to make a quick buck, the good genes for breed soundness, breed

traits and good temperament are needed more than ever. Desexing a purebred female cat with good breed

characteristics, good temperament and no genetically heritable defects/diseases will

count as a loss for that breed's quality in general, particularly if there are a lot of subquality

females around saturating the breeding circles.

3. Loss of estrogen or underexposure to estrogen as a result of desexing (especially early age desexing) may result in underdevelopment of feminine characteristics,

retention of immature juvenile behaviours and cause urinary incontinence:

The ovaries are responsible for producing progesterone and estrogen: the hormones that make mature female animals look and act like female animals. It is the hormones produced by the ovaries that cause female animals to develop the distinctive body characteristics normally attributed to the entire female animal. These include: increased vulval size and development;

mature breast (mammary) development and enlargement; increased maturity and emotional development; increased sex drive and libido and, controversially, improved bladder control and continence.

Desexing, particularly early age desexing (prior to the first season), may limit the development of mature feminine features such that they remain immature and juvenile-looking throughout life (i.e. the mammaries remain tiny and the vulva remains tiny). Early desexing may also cause the spayed pet to remain emotionally and mentally immature well into adulthood (i.e. the animal

retains many of its juvenile, kittenish behavioural characteristics). Not that this is always a problem. The immature body characteristics rarely pose a problem for the cat

and emotionally immature cats retain a lot of the playfulness and curiosity of their kitten-hood:

cute traits that most cat-loving owners are all too keen to keep hold of.

The incontinence issue is still a matter of debate (see FAQ 6, section 8, for more info). It has

long been said that estrogen plays a significant role in the development and maturation

of bladder sphincter tone (basically, how 'tight' and resistant to urine leakage the bladder neck is)

and that early age spaying can result in a weakness of this bladder tone, such that

the animal is prone to incontinence and urine leakage (i.e. dribbling urine involuntarily, particularly during sleep). Certainly, the once-common use of oestrogen products (e.g Stilbestrol)

in the management of female incontinence problems does support this idea as does the fact

that most of our incontinent pets (esp. dogs) are desexed females. As will be discussed in FAQ 6, however, although there is much merit to the desexing-causing-incontinence idea (particularly in the case of dogs and early-age spaying), there is still some controversy about whether it is the loss of oestrogen per se that produces the problem

or whether it is the spay technique itself (i.e. changing spay techniques may alleviate the risk).

Either way, regardless of the underlying causative mechanism, when it does occur, post-desexing incontinence and urine soiling can be a major problem for the animal and its owner.

This is particularly so if the animal lives indoors (wetting on the bed or carpet is unhygienic and poorly tolerated) or in a place with high blowfly populations (urine soiled

bottoms are prone to flystrike). The risk of the condition happening is certainly a significant reason why many owners (in particular, dog owners) might decide against having their female animals desexed.

Important author's note: In the case of female cats, I do not personally feel that the fear

of post-spay-incontinence is quite as warranted in this species as it is in dogs. Post-desexing incontinence is very uncommon in cats compared to dogs (I have never seen it and reference 22

also calls the condition rare in this species) and it is certainly not a reason

to avoid having female cats desexed.

4. As an elective procedure, spaying is risky:

Certainly, female cat desexing is a more risky and invasive procedure to perform than male cat desexing is. Having said that, the incidence of major complications associated with routine (i.e. non-pregnant, non-diseased uterus) spaying procedures is still very low and, therefore, no reason to avoid having a cat spayed. See sections 6 and 7 for more on spay complications.

5. As an elective procedure, spaying costs too much:

The high cost of veterinary services, including desexing, is another reason why some

pet owners choose not to get their pets desexed. See section 9 for more on the costs of neutering.

Author's note: Having said this, the costs of feline caesarian section or having a pregnant cat desexed are significantly higher than the cost of a routine spay.

6. The cat will "no longer be a woman" without her ovaries and uterus:

It sounds silly, but it is a very common reason why many owners refuse to get their female cats and dogs spayed. See myth 2 (section 8b) for more.

3. Information about cat spaying age: when to spay a cat.

The following two subsections discuss desexing age recommendations and how they have been established as well as the pros and cons of early age (8-16 weeks) spaying (early spay).

3a. Current desexing age recommendations.

In Australia and throughout much of the world, it has always been recommended that female cats be

neutered at around 5-7 months of age and older (as far as the "older" goes, the closer to the

5-7 months of age mark the better - there is less chance of your female cat becoming pregnant or developing a ovarian or uterine disorder or a hormone-mediated medical condition if she is desexed at a younger age).

In addition to this, it has always been stated that it is best if the cat is desexed prior to

the onset of its first season as this will potentially reduce the risks of the animal developing

mammary cancer in the future.

The reasoning behind this 5-7 month age specification is mostly one of anaesthetic safety for elective procedures.

When asked by owners why it is that a cat needs to wait until 5-7 months of age to be desexed, most veterinarians will simply say that it is much safer for them to wait until this age before undergoing a general anaesthetic procedure. The theory

is that the liver and kidneys of very young animals are much less mature than those of older animals and therefore less capable of tolerating the effects of anaesthetic drugs and less effective at metabolizing them and breaking them

down and excreting them from the body. Younger animals are therefore expected to have

prolonged recovery times and an increased risk of suffering from severe side effects, in particular liver and kidney damage, as a result of general anaesthesia. Consequently, many vets will choose not to anesthetize a young kitten until at least 5 months of age for

an elective procedure such as neutering.

The debate:

Whether this 5-7 month age specification for general anaesthesia and desexing is valid nowadays (2008 onwards), however,

is much less clear and is currently the subject of debate. The reason for the current

desexing-age debate is that the 5-7 month age specification was determined ages ago, way back in the days when animal anaesthesia was nowhere near as safe as it is now and relied heavily upon drugs that were more cardiovascularly depressant than modern drugs (e.g. put more strain on the kidneys and liver) and required a fully-functioning, almost-adult liver and kidney to metabolize and excrete them from the body. Because modern animal anaesthetic drugs are so much safer on young animals than the old drugs used to be, there is increasing push to drop the age of desexing in veterinary practices. This puts us onto the topic of early age neutering (see next section - 3b).

Are there any disadvantages to desexing at the normal time of 5-7 months of age?

Just as there are disadvantages associated with desexing an animal at a very young age (see section 3b), there

are also some disadvantages associated with desexing at the usually-stated age of 5-7 months:

- Some people find it inconvenient to wait until 5-7 months of age to desex.

- There is the chance that an early-maturing female cat may be able to mate and produce unwanted kittens before this age. This is not only bad for the underage mother cat (a mother cat

allowed to have kittens at under 5-7 months is not physically or emotionally mature enough to have

kittens - she is still a baby herself), but it potentially adds to the number of unwanted litters being destroyed and/or dumped.

- For people who choose to have their pets microchipped during anaesthesia, there is an inconvenient

wait of 5-7 months before this can be done. If the animal gets lost prior to this age, the unchipped cat may fail to find its way home.

- Some of the behavioural issues commonly associated with entire female animals may

become manifest before the time of the desexing age recommendations (e.g. urine spraying, roaming). These behavioural problems, once established, may persist and remain problematic even after the animal is sterilized.

3b. Spaying kittens - information about the early spay and neuter of young cats (kitten desexing).

As modern pet anesthetics have become a lot safer, with fewer side effects, the

debate about the recommended age of feline neutering has been reopened in the veterinary world

with some vets now allowing their clients to opt for an early-age spay or neuter, provided they

appreciate that there are greater, albeit minimal, anaesthetic risks to the very young pet when compared to the

more mature pet. In these situations, cat and dog owners can now opt to have their male and female

pets desexed as young as 8-9 weeks of age (the vet chooses anaesthetic drugs that are not as cardiovascularly depressant and which do not rely as heavily upon extensive liver and kidney metabolism and excretion).

As modern pet anesthetics have become a lot safer, with fewer side effects, the

debate about the recommended age of feline neutering has been reopened in the veterinary world

with some vets now allowing their clients to opt for an early-age spay or neuter, provided they

appreciate that there are greater, albeit minimal, anaesthetic risks to the very young pet when compared to the

more mature pet. In these situations, cat and dog owners can now opt to have their male and female

pets desexed as young as 8-9 weeks of age (the vet chooses anaesthetic drugs that are not as cardiovascularly depressant and which do not rely as heavily upon extensive liver and kidney metabolism and excretion).

Powerful supporters of early spay and neuter - in 1993, the AVMA (American Veterinary Medical Association) advised that

it supported the early spay and neuter of young dogs and cats, recommending that puppies

and kittens be spayed or neutered as early as 8-16 weeks of age.

IMPORTANT - because of the rising problems of pet and feral animal overpopulation,

it is now the law in many states (e.g. Canberra, Australian Capital Territory) for kittens

to be desexed prior to 12 weeks of age. What this means is that early age desexing is now compulsory, regardless of any (minor) anaesthetic risks to the animal, and

veterinarians who advise desexing at 5 months of age onward are breaking the law. Owners of

cats (and dogs) need to check their local state laws on pet neutering ages.

The advantages of the early spay and neuter of young cats:

Certainly, there are some obvious advantages to choosing to desex an animal earlier rather

than later. These include the following:

- People do not have to wait 5-7 months to desex their pets. The procedure can be over and done with earlier.

- Cats spayed very early will not attain sexual maturity and will therefore be unable to fall pregnant and give

birth to any kittens. This role in feline population control is why most shelters choose to neuter early.

- Cats spayed very early will not attain sexual maturity and will therefore be unable to fall pregnant. Consequently, owners of female cats will not have to deal with the dilemma of having an 'accidentally' pregnant pet and all of the ethical issues this problem poses (e.g. What do I do with the kittens? It is right to desex a pregnant animal before the kittens are born? Is it right to give a cat an abortion? ... and so on). Likewise, veterinary staff also benefit from not having to perform desexing surgery on pregnant animals, a procedure that many staff find very confronting.

- It makes it possible for young kittens (6-12 weeks old) to be sold by breeders and pet-shops already desexed. This again helps to reduce the incidence of irresponsible breeding - cats sold already desexed cannot reproduce.

- For owners who choose to get their pets microchipped during anaesthesia, there is no inconvenient wait of 5-7 months before this can be done.

- Some of the behavioural problems and concerns commonly associated with entire female animals may be prevented altogether if the kitten is desexed well before achieving sexual maturity (e.g. marking territory, roaming, calling,

in-heat aggression).

- Some of the medical problems and concerns commonly associated with entire female animals may be prevented altogether if the kitten is desexed well before achieving sexual maturity. In particular, breast cancer (mammary cancer)

in dogs (and maybe cats) is almost non-existent in animals that are desexed prior to their first season.

- From a veterinary anaesthesia and surgery perspective, the duration of spay surgery and anaesthesia is much shorter for a smaller, younger animal than it is for a fully grown, mature animal. I take about 5 minutes to neuter a female kitten of about 9 weeks of age compared to about 10 minutes for an older female and even longer if she is in-heat or pregnant.

- The post-anaesthetic recovery time is quicker and there is less bleeding associated with an early spay or neuter procedure.

- From a veterinary business perspective, the shorter duration of surgery and anaesthesia time is good for business. More early age neuters can be performed in a day than mature cat neuters and less anaesthetic is used on each individual, thereby saving the practice money per procedure.

- Routine, across-the-board, early spay and neuter by shelters avoids the need for a sterilization contract to be signed between the shelter and the prospective pet owner. A sterilization

contract is a legal document signed by people who adopt young, non-desexed puppies and kittens, which declares that they will return to the shelter to have that dog or cat desexed when it has reached the recommended sterilization age of 5-7 months. The problem with these sterilisation contracts is that, very often, people do not obey them (particularly

if the animal seems to be "purebred"); they are rarely enforced by law and, consequently, the adopted animal is left undesexed and able to breed and the cycle of pet reproduction and dumped litters continues.

The disadvantages associated with the early spay and neuter of young kittens:

There are also several disadvantages associated with choosing to desex an animal earlier rather

than later. Many of these disadvantages were outlined in the previous section (3a)

when the reasons for establishing the 5-7 month desexing age were discussed and include:

- Early age anaesthesia and desexing is never going to be as safe as performing the procedure on an older and more mature cat. Regardless of how safe modern anaesthetics

have become, the liver and kidneys of younger animals are considered to be less mature

than those of older animals and therefore less capable of tolerating

the effects of anaesthetic drugs and less effective at metabolizing them and breaking them

down and excreting them from the body. Even though it is very uncommon, there will always be the occasional early age animal that suffers from potentially life-threatening

side effects, in particular liver and kidney damage, as a result of young age anaesthesia. Having said that, the

anaesthesia time is heaps quicker, so maybe it all balances out ...

- There is an increased risk of severe hypothermia (cold body temperatures) and

hypoglycemia (low blood sugar) occurring when young animals are anesthetized. This

hypothermia predisposition is caused by the young animal's increased body surface area (larger area for heat to be lost), reduced ability to shiver and reduced body

fat covering (fat insulates against heat loss). The predisposition towards hypoglycemia is the result of a reduced ability to produce glucose from stores of glycogen and body fat as well as the fact that these stores of fat and glycogen are smaller in the young animal.

- Loss of sex hormone production at a very early age, as a result of desexing, may

result in extremely immature development of feminine body characteristics. In particular, the animal's

vulva and mammaries will remain very small and immature. Vulval hypoplasia (a small, juvenile vulva)

may become a problem in overweight animals as they will often develop a roll of fat over their vulva which can

predispose them to urine scalding and vulval skin infections (+/- urinary tract infections).

- Early neutering may result in retained juvenile behaviours inappropriate to the animal's age later on.

- Early neutering may result in urinary incontinence later on (but so can later neutering too).

Note - I haven't encountered this issue in a cat, however.

- Early age neutering prevents cat breeders from being able to accurately determine which kittens will be valuable stud animals (i.e. it is too early to tell when they are only kittens). Because desexing equates to a loss of breeding potential and valuable genetics, many breeders choose to only desex their cats after they have had some time to grow (after all, it is not possible to look at a tiny kitten and determine whether or not it will have the right color, conformation and temperament traits to be a breeding and showing cat). This allows the breeder time to determine whether or not the animal in question will be a valuable stud animal or not.

- Early spaying and neutering will not 100% reduce pet overpopulation and dumping problems when a large proportion of dumped animals are not merely unwanted litters, but purpose-bought, older pets that owners have grown tired of, can't manage, can't train and so on. Those people, having divested themselves of a problem pet, then go and buy a new animal, thereby keeping the breeders of dogs and cats in good business and promoting the ongoing over-breeding of animals.

Author's note: at the time of this writing, I was working as a veterinarian in a high

output animal shelter in Australia. Because shelter policy was not to add to

the numbers of litters being born irresponsibly by selling entire animals, all cats, including kittens, were required to be desexed prior to sale. Consequently, it was not unusual for us to desex male and female puppies and kittens at early ages (anywhere from 8 weeks of age upwards). Hundreds of puppies and kittens passed under the surgeon's knife every year on their way to good homes

and I must say from experience that the incidence of intra- and post-operative complications that were a direct

result of underage neutering was exceedingly low.

4. Cat spaying procedure (spay operation) - a step by step pictorial guide to feline spay surgery.

As stated in the opening section, spaying is the surgical removal of a female cat's internal reproductive organs. During the procedure, each of the female cat's ovaries and uterine horns are removed along with a section of the cat's uterine body. And, to be quite honest, from a general pet owner's perspective, this is probably all of the information that you really need to know about the surgical process of desexing a female cat.

Desexing basically converts this ...

Image: This is a preoperative picture of an anesthetized female cat, just prior to cat spaying surgery.

... into this ...

Image: This is a photo of the same cat after her reproductive organs have been removed surgically. All you can see from the outside is a small suture in the middle of her belly.

... by removing these.

Image: This is a picture of a feline reproductive tract, which has been removed by sterilisation surgery. You can clearly see the ovaries, uterine horns and uterine body: these are the main sites of hormone production, ova/egg production and kitten development in the female animal.

For those of you readers just dying to know how it is all done, the following section contains a step by step

guide to the pre-surgical and surgical process of desexing a female cat (ovariohysterectomy procedure). There are many surgical desexing techniques available for use by veterinarians, however, I have chosen to demonstrate the very commonly-used "midline incision procedure" of feline spaying. Diagrammatical images are provided to illustrate the process and I have included links to my

photographic step-by-step pages on feline spaying procedure and pregnant cat spaying procedure.

SPAYING PROCEDURE STEP 1:

Preparation of the animal prior to entering the veterinary clinic.

Preparation of an animal for any surgical procedure begins in the home.

Preparation of an animal for any surgical procedure begins in the home.

Your animal should be fasted (not fed any food) the night before a surgery so that she has no food in her stomach

on the day of surgery. This is important because cats that receive a general anaesthetic

may vomit if they have a full stomach of food and this could lead to potentially fatal complications. The cat could choke on the vomited food particles or inhale them into its lungs resulting

in severe bronchoconstriction (a reaction of the airways towards irritant food particles, common in cats,

which results in them spasming and narrowing down in size such that the animal can not breathe)

and even bacterial or chemical pneumonia (severe fluid and infection build-up within the air spaces of the lungs).

The cat should be fed a small meal the night before surgery (e.g. 6-8pm at night) and then not fed after this. Any food that the animal fails to consume by bedtime should be taken

away to prevent it from snacking throughout the night.

Young puppies and kittens (8-16 weeks) should not be fasted for more than 8 hours prior to surgery.

Water should not be withheld - it is fine for your feline pet to drink water before admission into the vet clinic.

Please note that certain animal species should not be fasted prior to surgery or, if they

are fasted, not fasted for very long. For example, rabbits and guinea pigs are not

generally fasted prior to surgery because they run the risk of potentially fatal intestinal paralysis (gut immotility) from the combined effects of not eating and receiving anaesthetic drugs. Ferrets have a rapid intestinal transit time (the time taken for food to go from the stomach to the colon)

and are generally fasted for only 4 hours prior to surgery.

If you are going to want to bath your female cat, do this before the surgery because you will

not be able to bath her for 2 weeks immediately after the surgery (we don't want the healing spay wounds to get wet).

Your vet will also thank you for giving him/her a nice clean animal to operate on.

SPAY PROCEDURE STEP 2:

The animal is admitted into the veterinary clinic.

When an animal is admitted into a veterinary clinic for desexing surgery, a number of things will happen:

- 1) You should arrive at the vet clinic with your fasted cat in the morning. Vet clinics usually tell owners what time they should bring their pet in for surgical admission and it is important that you abide by these admission times and not be late. If you are going to be

late, do at least ring your vet to let him know. Vet clinics need to

plan their day around which pets arrive and do not arrive for surgery in the morning. A pet turning up late throws all of the day's planning out the window. Do remember that your vet has the right to refuse to admit your pet for surgery if you arrive late.

- 2) The animal will be examined by a veterinarian to ensure that she is healthy for surgery. Her gum color will be assessed, her heart and chest listened to and her temperature taken to ensure that she is fit to operate on. Some clinics will even take your pet's blood pressure. This pre-surgical examination is especially important if your pet is old (greater than 7-8 years). In addition to the routine health check, your cat will also be examined in order to determine whether or not she is in-heat or pregnant.

If she is, the vet will discuss the added costs and risks of the spaying procedure with you and you can decide whether you want to continue with the operation or post-pone it.

- 3) You will be given the option of having a pre-anaesthetic blood panel done. This is a simple blood test that is often performed in-house by your vet in order to assess your cat's basic liver and kidney function. It may help your vet to detect underlying liver or kidney disease

that might make it unsafe for your cat to have an anaesthetic procedure. Better to know that there is a problem before the pet has an anaesthetic than during one! Old cats (>8 yrs) in particular should have a pre-anaesthetic blood panel performed (many clinics insist upon it),

but cautious owners can elect to have young pets tested too.

- 4) The dangers and risks of having a general anaesthetic procedure will be explained to you. Please remember that even though spaying is a "routine" surgery for most vet clinics, animals can still die from surgical and/or anaesthetic complications. Animals can have sudden, fatal allergic reactions to the drugs used by the vet; they can have an underlying disease that no-one is aware of, which makes them unsafe to operate on; they can vomit whilst under anaesthesia and choke and so on. Things happen (very rarely, but they do) and you

need to be aware of this before signing an anaesthetic consent form. Remember that the risks

are greater with in-heat and pregnant animals.

- 5) You will be given a quote for the surgery. Remember that the costs of spay

surgery will increase if your cat is in-heat (in season) or pregnant.

- 6) You will be asked to sign an anaesthetic consent form. As with human medicine, it is becoming more and more common these days for pet owners to sue vets for alleged malpractice. Vets today require clients to sign a consent form before any anaesthetic procedure is performed so that owners can not come back to them and say that they were not informed of the risks of anaesthesia, should there be an adverse event.

- 7) Make sure that you provide accurate contact details and leave your mobile phone on so that your vet can get in contact with you during the day! Vets may need to call owners if a complication occurs, if an extra procedure needs to be performed on the pet or if the pet has to stay in overnight.

- 8) Your cat will be admitted into surgery and you will be given a time to return and pick it up. It is often best if you ring the veterinary clinic before picking your pet up just in case it can not go home at the time expected (e.g. if surgery ran late).

SPAYING PROCEDURE STEP 3:

The cat will receive a sedative premedication drug (premed) and, once sedated, it will be given a general anaesthetic and clipped and scrubbed for surgery.

The cat is normally given a sedative-containing premedication drug before

surgery, which is designed to fulfill many purposes. The sedative calms the feline making

it slip into anaesthesia more peacefully; the sedative often contains a pain relief

drug (analgesic), which reduces pain during and after surgery and the sedative action results

in lower amounts of anaesthetic drug being needed to keep the animal asleep. Depending

upon the premedication drug cocktail given, other specific effects may also be achieved including:

reduction of saliva production and airway secretions (this reduces drooling and the

risk that saliva and respiratory secretions may be inhaled into the lungs during surgery);

improved blood pressure; airway dilation (making it easier to breathe) and so on.

General anaesthesia is normally achieved by giving the cat an intravenous injection of

an anaesthetic drug, which is then followed up with and maintained using the same injectable

drug or, more commonly, an anaesthetic inhalational gas. The animal has a tube inserted down its throat during the surgery to help it to breathe better; to stop it from inhaling any saliva or vomitus and to facilitate the administration of any anaesthetic gases.

The skin over the animal's belly is shaved and

scrubbed with an antiseptic solution prior to surgery.

Image: This is a picture of a cat's belly being scrubbed and cleaned with an antiseptic

scrub in preparation for surgery.

The surgery:

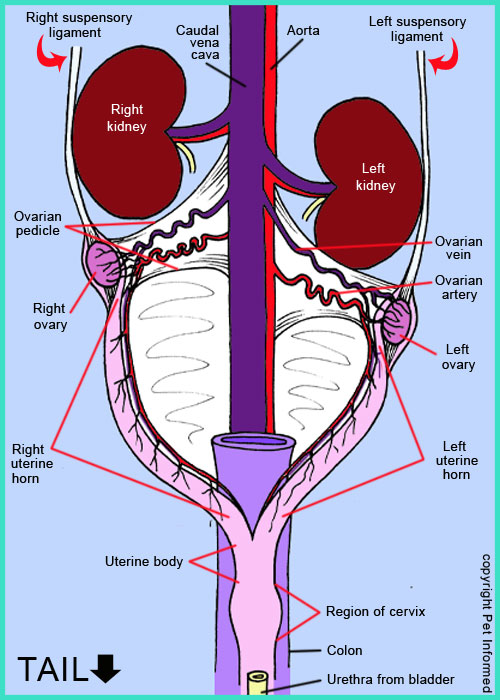

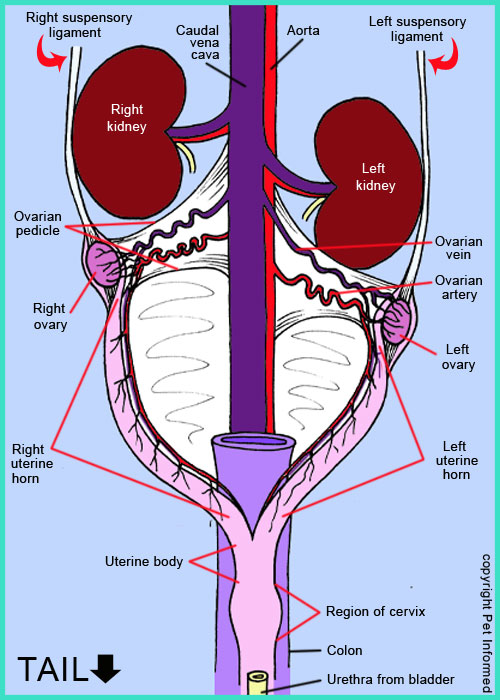

In order for you to properly understand the process of cat spaying surgery, I have to take a second to explain the anatomy of the female cat's reproductive organs.

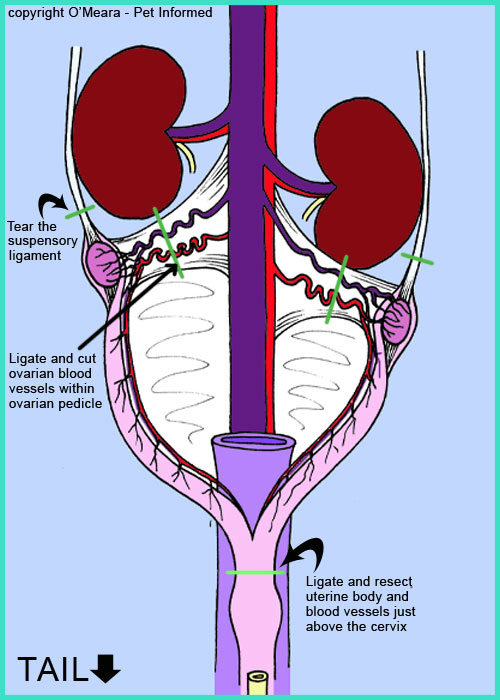

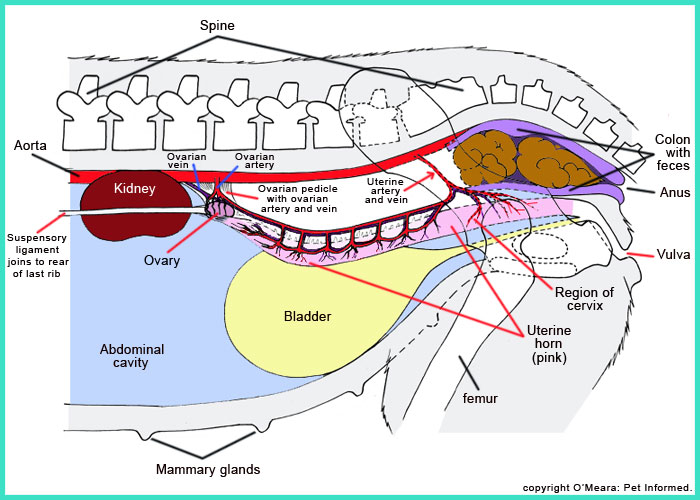

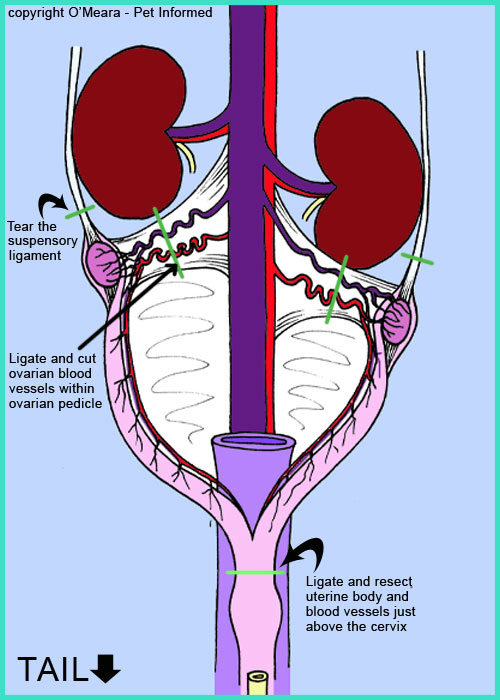

Image: This is a diagram of the reproductive anatomy of a female dog as it appears when

the abdomen is incised and entered from the abdominal midline. This anatomy also holds true for the female cat except that the suspensory ligaments, important in the bitch, are of little significance in the cat. I have not drawn in the intestines or bladder (aside from the stump of the bladder neck - bottom), which would normally overlie the animal's reproductive structures when the animal is positioned on its back (the

reproductive organs occupy the roof of the abdomen, near the animal's spine and kidneys).

Of particular importance, when it comes to feline spay surgery, are the fatty ovarian pedicles (the tubes of

dense fat and connective tissue containing the ovarian arteries and veins) and the uterine body, just ahead of the animal's cervix. These are the highly vascular sites that must be tied off securely with sutures (so that they do not bleed) and cut in order for the uterus and ovaries to be removed.

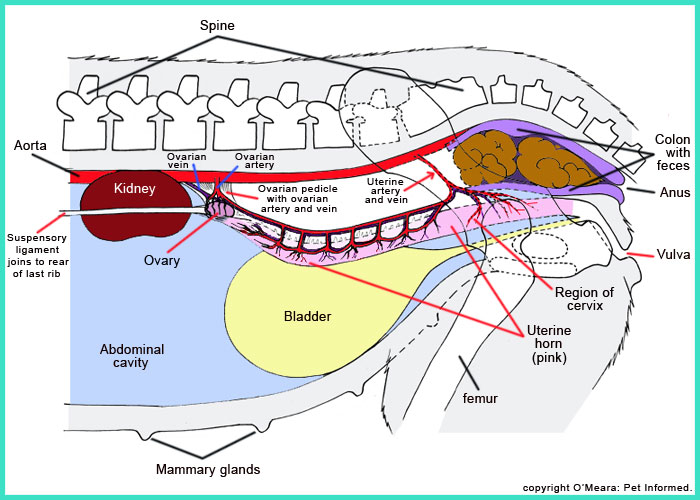

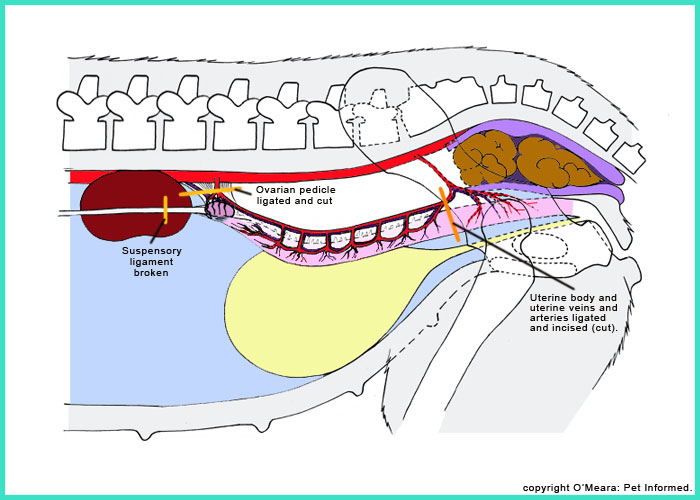

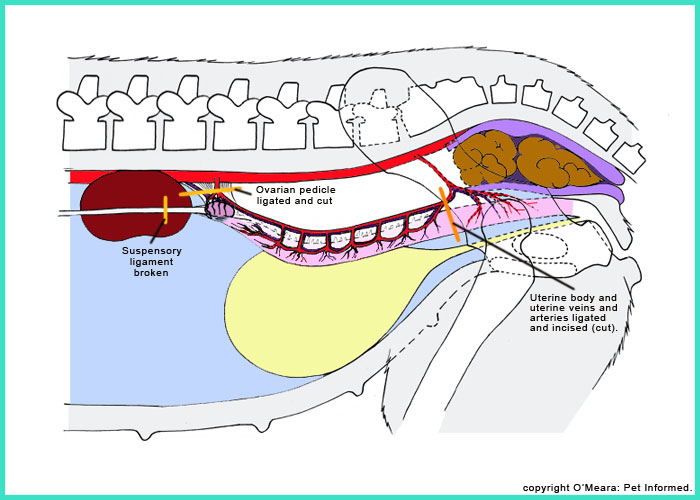

Image: This is a diagram of the reproductive anatomy of a female dog as it appears from the

side. This anatomy also holds true for the female cat except that the suspensory ligament, important in the bitch, is of little significance in the cat. I have drawn this view in order to give you a three-dimensional idea of where the uterus sits in the dog or cat (it is located very high within the

abdomen). This is the anatomy that would be encountered if the veterinarian performed a flank spay

(a spay technique whereby the veterinarian enters the animal's abdominal cavity via an incision made

through the muscles of the animal's flank). I have not drawn in the intestines or colon (aside from the stump of the colon/rectum), which would take up most of the anterior blue space

indicated in this diagram.

Of particular importance, when it comes to feline spay surgery, are the fatty ovarian pedicles (the tubes of

dense fat and connective tissue containing the ovarian arteries and veins) and the uterine body, just ahead of the animal's cervix. These are the highly vascular sites which must be tied off securely with sutures (so that they do not bleed) and incised (cut) in order for the uterus and ovaries to be removed from the animal. Failure to ligate (tie off) these

regions will result in severe abdominal hemorrhage.

CAT SPAYING PROCEDURE STEP 4:

The skin is incised and the cat's abdomen entered.

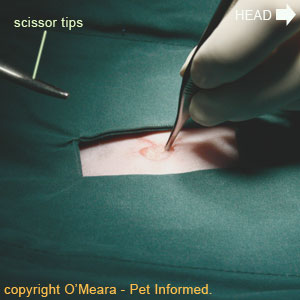

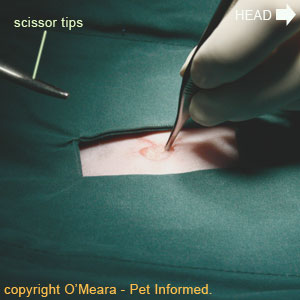

Photograph 1: A small incision (usually around 1cm long, but can be up to 3-4 cm long) is made in the cat's skin, approximately 1 inch below the umbilical scar on the abdominal midline.

Picture 2: In this image, the veterinary surgeon is removing some of the fat (termed subcutaneous fat, sub-q fat or SC fat) from the incision line region. The fat is the white, shiny substance in the center of the incision line.

There is generally a lot of fat located between the cat's skin and its abdominal wall

muscles. The veterinarian will often cut a small amount of this fat away, allowing easy access to

and visualisation of the cat's abdominal wall muscles.

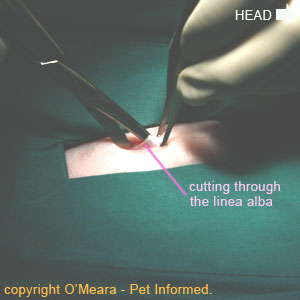

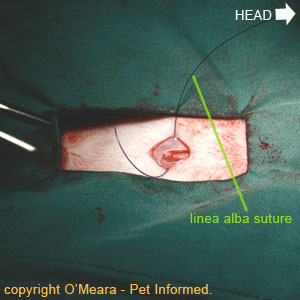

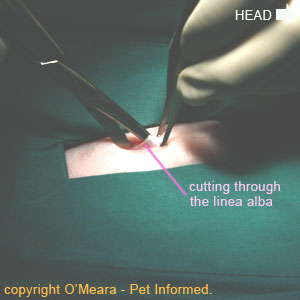

Image 1: The veterinarian enters the cat's abdominal cavity by cutting through the abdominal

wall musculature on the midline of the abdomen. The veterinarian aims to cut along a central line of scar tissue that joins the right and left sides of the animal's abdominal wall musculature.  This line of scar tissue is called the linea alba (literally meaning - "white line").

By cutting through scar tissue, rather than the red muscle located either side of the linea alba, the veterinarian reduces the amount of bleeding incurred in entering the cat's abdominal cavity.

This line of scar tissue is called the linea alba (literally meaning - "white line").

By cutting through scar tissue, rather than the red muscle located either side of the linea alba, the veterinarian reduces the amount of bleeding incurred in entering the cat's abdominal cavity.

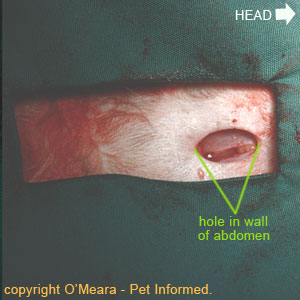

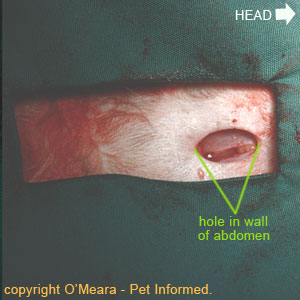

Photograph 2: This is a close-up picture of the incision line after the linea

alba has been incised. You can see the hole going into the abdominal cavity.

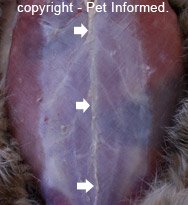

Photo 3 (right): This is a post-mortem image of a cat's abdominal wall muscles. The skin has

been removed and the linea alba (white line) is clearly visible.

CAT SPAY PROCEDURE STEP 5:

The ovarian pedicles and uterine body are ligated (tied off) and cut and the uterus and ovaries are removed

from the abdomen.

Image: This is the same diagram that I presented earlier, showing the reproductive

anatomy of the female dog or cat. In this diagram, the sections of the reproductive anatomy that are ligated (tied closed with sutures) and incised (cut through) are indicated with green lines. This tying-off and cutting procedure needs to be performed with great care, otherwise there is the risk of severe internal bleeding occurring or a section of ovary being left behind (ovarian remnant), which could result in the animal returning to heat (showing signs of heat) after it has been 'desexed'.

Author's note: In the case of cat spay surgery, the right and left suspensory ligaments

are not usually taken into account. These ligaments are only really important in dog spaying surgery

since they need to be broken in order for the canine ovarian pedicles

(ovarian arteries and veins) and ovaries to be accessed, ligated and transected (cut).

Image: This is the same diagram that I presented earlier, showing the reproductive

anatomy of the female dog or cat when taken from a side-on (lateral) vantage point. In this diagram, the sections of the reproductive anatomy that are ligated (tied closed with sutures) and incised (cut through) are indicated with orange lines. This procedure needs to be done with great care

otherwise there is the risk of severe internal hemorrhage occurring or a section of

ovary being left behind (ovarian remnant), which could result in the animal returning to season

(showing signs of heat) even though it has been 'desexed'.

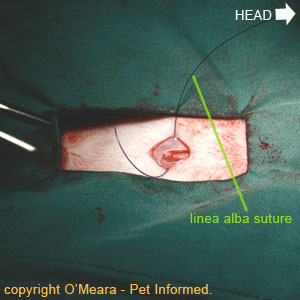

SPAYING CATS PROCEDURE STEP 6:

The abdominal wall is sutured closed.

Pictures: After the uterus and ovaries have been removed, the surgeon uses absorbable suture material to close the hole in the cat's abdominal wall musculature (linea alba). Because the linea alba is essentially a tendon-like, collagenous structure (made of collagen), it has less blood supply than red muscle and, therefore, takes longer to heal than muscle would. To take this slower healing into account, the veterinarian often uses a longer-lasting suture (a suture

that is slower to lose its strength and slower to absorb) to close the linea alba. Because

this suture absorbs over time, the vet does not have to remove it later on.

Image:The linea alba has been sutured closed.

SPAYING CATS PROCEDURE STEP 7:

The subcutaneous fat layer is sutured closed.

Photo: The subcutaneous fat layer (also called the SC or sub-q layer) is sutured closed. This layer closure acts to reduce the amount of open space (called 'dead space') located between the abdominal wall and skin layers, thereby reducing the risk of a large, fluid-filled swelling

(called a seroma) forming at the surgery site. Basically, whatever space/gap you leave in a surgery site, fluid

will pool in - by closing down this open space (dead space), the vet surgeon essentially

leaves fewer sites available for inflammatory fluids to pool in.

SPAYING CATS PROCEDURE STEP 8:

The skin layer is sutured closed.

Images: The surgeon is closing the skin using non-absorbable skin sutures. These

will need to be removed in 10-14 days.

Image: Absorbable skin sutures can also be placed. These are called intradermal sutures

and they do not need to be removed. They look like a line with no suture material showing.

They are useful because cats find it harder to chew them out.

A Photographic Guide to Cat Spay Surgery:

If you would like to view a complete, step-by-step, photographic guide to feline

desexing surgery, please visit our great Cat Spay Procedure page.

A Photographic Guide to Spaying a Pregnant Cat:

As will be discussed in the FAQs and Myths section (section 8), it is possible to desex a

female cat who is already pregnant. What should be understood, however, is that the desexing

of pregnant animals carries with it a much higher risk than the desexing of non-pregnant

females does (the ovarian and uterine blood vessels are much larger and bleed a lot more and the uterus

itself is greatly enlarged and much more friable and prone to tearing apart, compared to the non-pregnant

uterus). In viewing this page (which does contain images of surgical abortion) what should

be clear to you is that there is added danger and risk and pain (a bigger surgical incision) to the female animal in desexing her whilst she is pregnant and that, for this reason, the emphasis should

be placed on having a female cat desexed well before she manages to become pregnant. If you would like to view a complete, step-by-step, photographic guide to pregnant cat spaying surgery, please visit our informative Spaying a Pregnant Cat page.

5. Spaying After Care - all you need to know about caring for your female cat after spaying surgery.

When your cat goes home after spay surgery, there are some basic exercise, feeding,

bathing, pain relief and wound care considerations that should be taken into account to improve your

pet's healing, health and comfort levels.

1) Feeding your cat immediately after feline spaying surgery:

After a cat or kitten has been spayed, it is not normally necessary for you to implement any

special dietary changes. You can generally go on feeding your pet what it has always eaten. Some owners, however, like to feed their pets bland diets (e.g. boiled, fat-free, skinless chicken

or a commercial prescription intestinal diet such as Hills feline i/d)

for a few days after surgery in case the surgery and anaesthesia process has upset their tummies. This is not normally

required, but it is perfectly fine to do.

Unless your veterinarian says otherwise, it is normally fine to feed your cat the night after

surgery. Offer your pet a smaller meal than normal in case your pet has an upset tummy

from surgery and do not be worried if your pet won't eat the night after surgery.

It is not uncommon for pets to be sore and sorry after surgery and to refuse to eat that evening.

If your cat is a bit sooky and won't eat because of surgery-site pain, feel free

to tempt her with tasty, strong-smelling foods to get her to eat. Skin-free roast chicken

often works well and it is not too heavy on the stomach. Many cats also like strong-smelling

fishy foods like fish-containing tinned food, tinned tuna or salmon or cooked fish fillets

and small prawns. Avoid fatty foods such as mince, lamb, pork and processed meats (salami, sausages, bacon) because these may cause digestive upsets.

Be aware of your pet's medications and whether they need to be given with food. Some cats

go home on non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) such as Carprofen

(trade names include: Prolet, Rimadyl, Carprofen tablets) and Meloxicam (tradenames include Metacam)

after surgery. These drugs need to be given with food. Do not give these drugs if your cat is refusing to eat.

Most cats that get spayed are not normally off their food for more than a day. You should contact your vet if your pet does not eat for more than 24 hours after surgery.

2) Exercising your cat after neutering:

It takes 10-14 days for skin wounds to heal after surgery; even longer for the linea alba wounds to heal. It is therefore recommended that running-around exercise be avoided or minimized for a minimum of 2 weeks after surgery to allow the skin the best chance of staying still and healing. Restricting

your cat's exercise will also reduce the risk of a large seroma forming (section 6b) and

reduce post-operative spay-site pain.

Of course, many of you scoff at the idea of "keeping a cat or kitten rested and still!" It is, therefore, normally fine if your cat romps around quietly inside your house and performs its normal indoor activities and play. I would, however, avoid letting your cat

go outside until she has had time to heal (14 days minimum). This will prevent excessive exercise, which could

impede healing, and it will also prevent the feline spay wounds from becoming wet or

packed with mud and dirt (and thus infected). In addition to this, keeping your cat inside will ensure that she doesn't wander off and go missing for days on end. At least if she is kept inside, you will be able to find her and check on her progress and well-being daily.

3) Wound care after feline neutering surgery:

Normally you do not have to do anything special with your pet's surgical desexing wounds (e.g washing

and bathing them) after surgery. The most important thing you do need to do is monitor the wound to ensure that

it remains looking healthy and clean.

Check the abdominal suture line daily. Look out for any signs of redness, swelling and wound pain

(surgical wounds should not normally appear painful or red beyond the first 3-5 days after surgery). Look out for obvious signs of infection (e.g. a yellow or green pussy discharge) or signs

that the wound is breaking down (the wound will split and contain cheese-like white or yellow

necrotic tissue inside it if it is breaking down). If you see any of these signs, take the pet to

your vet for a check up.

If the wound site gets dirty (e.g. covered in mud or faeces), you can clean it with

warm salty water, saline (0.9% NaCl) or a very dilute betadine solution (betadine solution in water

made up to a weak-tea colour concentration) to remove the contamination. The wound and sutures should then be dried thoroughly to stop bacteria from wicking deep into the surgical site. The cleaned wound should then be closely monitored over the next few days because wounds soiled

in dirt or faeces are at high risk of becoming infected, even if they are bathed.

Do not let your pet lick its spay wounds! This is a major cause of surgery wound breakdown - the pet licks

the wounds and introduces mouth-bacteria into the wounds, making them wet and infected and unable to heal. In severe cases, the pet actually pulls out the sutures with its teeth

resulting in the wound breaking apart completely.

At the very first sign of wound licking, go to your vet immediately and get an

Elizabethan collar (E collar) for the cat. The collar will stop the pet from tampering with

the stitches and hopefully prevent wound break down and infection. If the cat starts licking

in the middle of the night and you can not get an E collar, you can cut the circular bottom out of an appropriately-sized, clean plastic flower pot (leave the drainage holes intact);

place this over your pet's head and neck like an Elizabethan collar and thread the pet's

collar or a stocking through the pot-plant drainage holes to secure it to your pet's neck. Be careful to place it so that your pet can not choke and go and get a proper E collar

from your vet in the morning.

Wound licking can also be reduced by putting bitter apple spray, methyl phthalate solution

or another commercial bitterant solution onto the pet's suture line. Wound-Gard is one

commercial product that serves this role (there are many other products that serve a

similar function).

Images:

Images: If your cat's spay wound looks like either of these, see a vet immediately.

The first image is spay site that has broken down because the cat pulled its skin sutures out. The

second image is an

emergency - all of the sutures, including the abdominal wall sutures,

have broken down and the cat's intestines are sticking out! This needs urgent surgery.

4) Bathing or washing your cat after cat spaying:

Because it takes 10-14 days for sutured (stitched) skin wounds to heal and seal closed, it is advised

that the animal not be bathed or allowed to go swimming for the first 14 days after surgery. Wetting the sutures before this time may allow bacteria to enter the surgery site and

set up an infection which could result in wound breakdown and abscess formation (bacteria are carried deep into the skin by the wicking capillary action of water traveling

along the sutures).

5) Suture removal after spaying surgery:

If your cat had superficial, non-absorbable skin sutures placed in its skin to close

its feline desexing wound, then these will need to be removed once the incision line has healed. Sutures are normally removed 10-14 days after surgery. They can be removed at home, but

ideally they should be removed by a veterinarian (the vet can determine if the wounds have healed up

enough before removing them). Vet clinics do not normally charge a fee for suture removal.

6) Pain relief after spaying:

In my experience, most cats do not seem to show all that much pain after spaying surgery. Many cats start playing and running around the very same night! If your pet is in pain, however,

there are ways that you can help.

Go to your vet for some analgesic pills or drops. Most vets send their neutering patients

home with a few days of pain relief as a matter of course, however, some vet clinics do not.

If you haven't been sent home with any pain relief for your pet and your pet shows signs of

pain after surgery, you can return to your vet clinic and request pain relief pills.

If your pet is very old or it has compromised kidney or liver function, certain pain

medications may not be recommended and other pain relief solutions may need to be found.

DO NOT self-medicate your pet with human pain-killers. Many human pain relief drugs are

toxic to cats. In particular,

never give a cat panadol or paracetamol (also called acetaminophen)!

Keep your cat confined and quiet and indoors. Pets that are allowed to run around after surgery

are more likely to traumatize and move their sutures, leading to swelling and

pain of the surgical site. Reducing activity means less pain.

Consider placing hot and cold compresses on your pet's surgical site to reduce pain

and swelling. Placing a dried-off ice pack wrapped in a tea towel (never put ice directly against the skin) on the pet's surgery site for 10 minutes and then placing a hot water bottle (also wrapped in

a tea towel) on the site for another 10 minutes and then replacing the cold pack and

so on (i.e. alternating hot and cold packs for about 30-45 minutes) can go a ways towards reducing surgery site pain

and swelling.

CAUTION - Only do this if you have a very nice tempered cat - remember that pets in pain can bite and