Lice Pictures - What Does Lice Look Like ?

This lice pictures page is designed to give pet owners a visual guide to the common lice species (louse species)

infesting domestic animals and answer the commonly-asked questions: "what is lice?" and "what does lice look like?" Everyone knows that they need to protect their pet cats, dogs, horses,

birds, rodents and livestock animals against lice infestation, but not everyone knows what lice or lice infestation actually looks like.

This lice pictures page is designed to give pet owners a visual guide to the common lice species (louse species)

infesting domestic animals and answer the commonly-asked questions: "what is lice?" and "what does lice look like?" Everyone knows that they need to protect their pet cats, dogs, horses,

birds, rodents and livestock animals against lice infestation, but not everyone knows what lice or lice infestation actually looks like.

You can't treat or control what you can't identify. This lice pictures page aims to make the identification

and recognition of lice problems in pets and livestock easier for pet owners so that

prompt lice treatment and ongoing lice control measures can be implemented much faster.

This veterinary advice page contains many different lice pictures and informative lice facts, including:

- real-life photos of lice infestation on domestic and wild animals (what does lice look like on animals?);

- biting louse (biting or chewing lice) and sucking louse (sucking lice) pictures;

- microscope images of lice and their eggs;

- microscopic photos of adult lice anatomy;

- pictures of lice eggs (lice nits) on the animal's coat;

- information about the signs of lice in animals;

- information about the factors contributing to the transmission and development of severe louse infestation and

- information about lice treatments (getting rid of lice) in various animal species.

The lice pictures topics are presented in the following order:

1) What is lice ? - a simple definition.

2) What does lice look like? - a description of the adult louse, egg (nit) and nymph.

3) Louse infestation pictures - photos of heavy infestations of horse lice (equine louse) and lice on mice (murine louse).

4) Lice pictures through the microscope - what does lice look like under the microscope?

5) Lice infestation in different domestic animal species.

This section contains detailed photos and information (including

lice treatment information) about lice in different animal species. To date, Pet Informed only has photos of lice in horses, cats, goats and mice. Lice pictures pertaining to various other domestic, avian and livestock animal species will appear on this page as they become available.

5a) Horse lice (horse louse) - equine louse information and treatment.

5b) Feline lice (cat louse) - cat lice treatment and information. 5c) Mouse lice (murine lice) - mice lice treatment and information.

5d) Goat lice (caprine lice) - goat lice treatment and information (also includes sheep lice treatment info).

6) Lice eggs (lice nits) - pictures of louse eggs (nits).

7) How can I tell if my pet has lice? - Telltale lice symptoms and signs of lice in cats and dogs and other animals.

1) What is lice? - a simple definition.

Lice

1) What is lice? - a simple definition.

Lice is the plural form of

louse. A louse is a small, flat, wingless insect that infests the hair, skin

and feathers of various species of domestic pets, livestock and birds. Certain species of louse (the body louse,

head louse and pubic louse) also infest humans. The various species of louse parasite infesting animals

and humans can be further described as being of either a

sucking louse variety (these small-headed

louse species drink the blood of their hosts to survive) or a

biting louse variety (these large-headed

lice species bite at the skin, hair and feathers of the host animal, feeding on the dander or skin/feather flakes

of the animal host).

The adult louse lays its eggs (termed

nits) on the host animal's fur or feathers such that

the entire lice life cycle, from adult to egg to adult, takes place on the host animal's coat or plumage (i.e.

there is no "off-host" or "environmental" stage of the lice life cycle). Because the entire louse life cycle

takes place wholly on the skin of the host animal (i.e. just one host animal will do), lice populations

can build up to very large numbers on the one host creature. When moderate to large populations of lice build up on the coat or plumage of a host animal, their many tiny lice bites can create significant signs of skin irritation and itchiness in that animal. This skin irritation is usually

manifest by the itchy host animal as scratching, biting, rubbing, over-grooming and trauma of the pelt (or plumage) and skin, which results in subsequent balding, hair-thinning, coat and feather damage and even outright trauma

to the host animal's coat/plumage and skin. Massive populations of bloodsucking lice types can sometimes also produce severe anaemia (blood loss) and weakness in addition to this annoying skin irritation.

The term "lice" is also used to refer to active infestation of the feathers and haircoat

of animals and people with various species of sucking and biting louse. To say that a

pet or a person "has lice" means that the individual's hair coat or feather plumage is infested with these irritating

parasites. The medical term for the parasite condition is "pediculosis".

2) What does lice look like? - a description of the adult louse, egg (nit) and nymph.

2) What does lice look like? - a description of the adult louse, egg (nit) and nymph.

Lice are small insects that parasitize the coats and plumage of a wide range of domestic and wild animal

species including: cats, dogs, mice, rats, guinea pigs, horses, livestock (goats, sheep, cattle), wild and cage birds, poultry, water-birds and humans. In appearance they are small insects, usually about 1-2mm in length, however, depending upon the louse species in question they can sometimes be quite a bit larger (bird lice are often very large - for example, swan lice can be up to about 5-8mm in length). Lice and their eggs (termed nits)

can usually be easily spotted with the naked eye. Lice bodies are usually white to very pale

yellow in color, with a darker orange-tan to brownish-colored head. Like ticks and mites, lice have a dorso-ventrally flattened, pancake-like shape (they look as though they have been squashed from above).

Like most other insects, lice have three main body parts: a head, a thorax

and an abdomen and, like most other insects, lice have six legs (three on each side) that originate from the mid-section of the body (thorax). The louse's legs are specially

shaped for gripping the host animal's fur or feather shafts. In the case of many sucking lice species, the legs and gripping claws (feet) are exceptionally large in size, compared to the size of the louse's body,

and very strong. The legs and gripping claws of many of the biting louse species are much smaller and weaker by comparison. The head and mouthparts of the louse are also equipped and shaped according to the louse's feeding style. Sucking lice, which feed on the blood of host animals, have a small head (narrower than the width of the louse's

thorax) and long, piercing mouthparts for drinking blood. Biting or chewing lice, which feed on the skin materials and dander of host animals, have a huge head (bigger than the width of the

thorax) and toothed, grinding, mandibular mouthparts for biting and chewing the skin.

Unlike many other insects, lice have no wings and do not fly. Lice move from host to host and from host to environment to host by direct host contact (lice infested hosts brushing up against the bodies of non-infested hosts)

and through direct contact with lice or nit infested bedding, brushes, nesting sites, yards and blankets.

Lice are mobile, but do not move at high speed. Pet owners can often easily find lice

clinging to the fur and feathers of their pets with a simple, but thorough, search.

Lice eggs (lice nits) are long, white, rice-shaped eggs, about 0.5-1mm in length (depending on the species). They are normally found firmly attached to the shafts of the fur or feathers, somewhere around the base of the hair coat and plumage. Owners can find lice eggs by parting the hair or feathers of the host animal and examining the fur and feather shafts close to the skin.

Lice eggs hatch to produce louse nymphs that are about 0.5-1.5mm long (or smaller or larger, depending on the louse species). There are three juvenile nymph stages (each new nymph stage is the result of the nymph stage before it

growing in size and shedding its skin - termed "molting" or "moulting"), which increase in size with every moult before finally becoming adult lice with the final moult. All three nymph stages simply look like undersized adults. There are no pupal or cocoon stages in the lice life cycle.

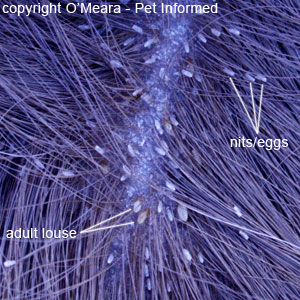

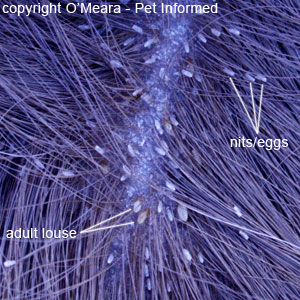

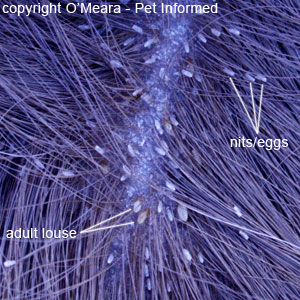

Pictures of lice 1 and 2:

Pictures of lice 1 and 2: These are images of a severe lice infestation on a horse's coat.

The adult lice are about 1-2mm long with large, pale bodies and darker coloured (reddish) heads. The lice eggs

or lice nits are long, narrow, white, rice-grain-like structures attached to the hair shafts of the horse's coat.

Author's note: In the second horse lice photo, I have labeled two of the lice as adult lice. In retrospect, these

"adult lice" are probably not adults at all, but louse

nymphs (immature pre-adult stages of the lice

life cycle that look identical to adult lice, except that they are smaller in size). The reason I believe that these two labeled lice are probably nymphs is because, if you look at the skin about 1cm to the right of the two lice in question, you'll see the body of an even larger louse. This much bigger

louse is probably a true adult louse, making the two smaller lice (indicated) nymphal stages. The amendment does serve to illustrate, however, how very similar the appearance is between the adult lice stages and their immature nymph stages.

Lice pictures 3:

Lice pictures 3: This is a picture of a

nymph stage louse (left) and an

adult stage louse (right).

The two sucking lice pictured were taken from the very same host animal (a mouse). This louse photo shows the large difference in size between the different lice life cycle stages.

3) Louse infestation pictures - photos of heavy infestations of horse lice (equine louse) and lice on mice (murine louse).

3) Louse infestation pictures - photos of heavy infestations of horse lice (equine louse) and lice on mice (murine louse).

This section contains images of severe lice infestations in the horse and mouse. It is not uncommon to see such severe infestations of lice in horses and livestock animals that are stressed,

malnourished, underweight, overcrowded, very aged or otherwise debilitated. Many parasite species take advantage of sickness or

debility in their hosts and lice are no exception. Louse infestations are particularly apt to become more severe

when horses and livestock animals are not checked regularly by their human masters. Domesticated rodents like mice and rats and guinea pigs are also prone towards severe infestations of lice because: they are often purchased from overcrowded, stressful, unhygienic, high-lice-transmission, unsavory breeding situations; they are often housed close-together in large numbers

(facilitating louse transmission) and rodent pet owners often don't examine the fur of their charges

all that closely. It is rarer by far to see such heavy louse infestations in dogs and cats (unless they are stray, feral or neglected) because most cat and dog owners tend to notice lice in their pet's coat well before the infestation has a chance to become too severe.

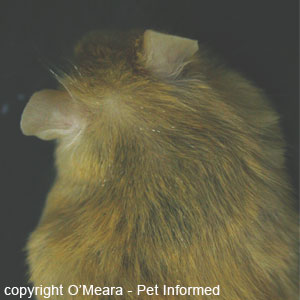

Equine lice picture 4:

Equine lice picture 4: This is a picture of a horse with a severe louse infestation. Notice how the horse's fur appears moth-eaten and patchy? The loss of fur is the result of the horse scratching itself up against trees and fences in an attempt to relieve the itchiness of the parasites' lice bites. This particular horse was very old, thin and crippled: a stressed, debilitated state that facilitated the multiplication of the insect pests.

Horse lice pictures 5 and 6:

Horse lice pictures 5 and 6: These are close up photographs of the coat of the lice horse in image 4. In these lice pictures, the horse's coat is coarse and rough and of poor quality and bears many patches of thinly-haired to

hairless bald spots, where the horse has broken the hair shafts scratching and rubbing itself up against trees and fences in an attempt to remove the lice infestation. Chronically damaged hair and skin can change colour and the hairs may grow back paler or darker in shade. You can get a sense of this in these horse lice pictures.

Horse lice photos 7, 8 and 9:

Horse lice photos 7, 8 and 9: These are lice pictures of some adult lice hanging onto the long hairs of the horse's outer coat. The adult lice in these lice pictures are the whitish-coloured insects clinging

to the hairs. Being in such an open position, these lice are perfectly placed

to infest the coats of any other horse hosts that happen to brush alongside this lice infested animal. These lice pictures show that, with a thorough inspection of the horse's coat, horse lice are not all that hard to find.

Take a closer look at lice picture 9 (the third louse picture in this grouping). It is a close-up

image of lice photo 8. Notice how the body or abdomen of the louse (pointing downward) is white and

oval shaped. Then notice the louse's head (pointing upwards) - it looks like a broad, brown-red triangle

sitting on top of the louse's body. The thorax (small and narrow) is hard to discern, but sits just between

the head and the abdomen. The large, broad, triangular-shaped head tells us that this is a biting louse (also called chewing lice) variety and that, as such, it is likely to be of the Order: Mallophaga and of the Species:

Damalinia equi.

Lice pictures 10 and 11:

Lice pictures 10 and 11: When the fur of this louse-infested horse was parted, particularly in the areas of the coat underneath the mane, alongside the neck and around the poll, withers and tail-base, clusters of lice and lice eggs (lice nits) could be found at the base of the hairs. These lice pictures show what this severe lice infestation looked like up close and provide an example

of what you might look for if trying to diagnose lice on a horse. The nymph and adult lice stages

(different sizes) are positioned against the horse's skin, head down and bottom up, chewing on the dander. Further up the hairs, small lice nits or eggs (which look like white grains of rice) can also be seen in these lice pictures.

Pictures of lice 12 and 13:

Pictures of lice 12 and 13: These lice pictures show a mouse with a moderate to severe

lice infestation. The fur of this mouse still looks quite good - there are no bald spots or places on the skin that

have been heavily traumatized through the rodent's scratching and excessive grooming activities. In the more magnified image (lice picture 13), the lice eggs or nits can now start to be seen on the mouse's fur as

chains of white ovals located along the shafts of a few of the hairs.

Mouse lice pictures 14, 15 and 16:

Mouse lice pictures 14, 15 and 16: This is the same louse infested mouse as that pictured in the images above. The lice nits can be clearly seen in image 14, as white, elongated objects that have been laid along the hair shafts of the mouse's fur. Lice photo 14 has been magnified in lice picture 15 and a couple of

the louse nits have been labeled for you. In louse photo 16, a heavily infested region of the

mouse's coat has been photographed - if you look very closely, you should be able to see

many lice eggs located all through the layers of the mouse's fur.

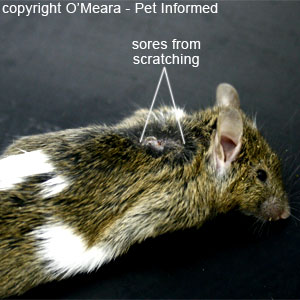

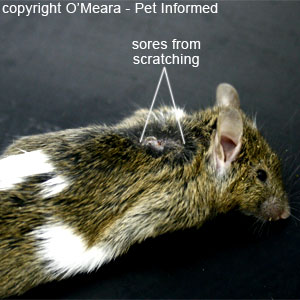

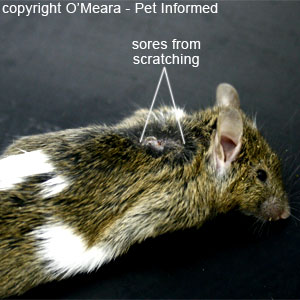

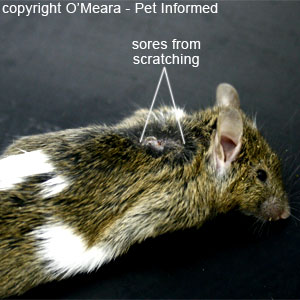

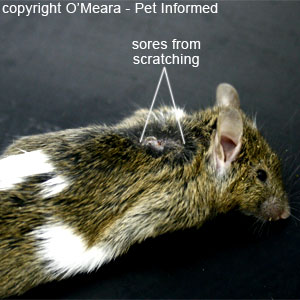

Lice pictures 17, 18 and 19:

Lice pictures 17, 18 and 19: This is another mouse with a severe louse infestation. Lice eggs were found on the hairs of this mouse, similar to the tan mouse above. The photos of this mouse were included because they illustrate the severe scratching and self-trauma that can occur as a result

of lice infestation. The mouse in these lice pictures had literally torn the fur from its body (notice the bald spots)

and had scratched its skin to the point of bleeding, leaving behind big sores and scabs on the skin. This severe self trauma can be one of the signs of lice that owners might recognize first

in their rodent pets - scratching and skin trauma should be a clue for owners to have a close look through their pet's coat for lice or nits.

4) Lice pictures through the microscope - what does lice look like under the microscope?

4) Lice pictures through the microscope - what does lice look like under the microscope?

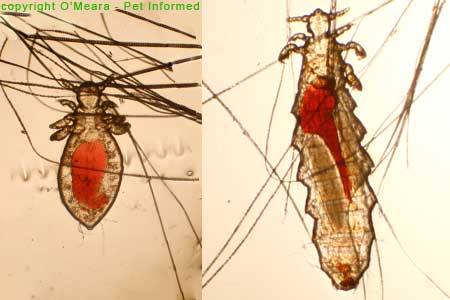

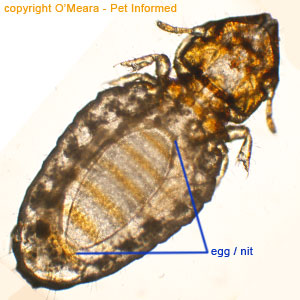

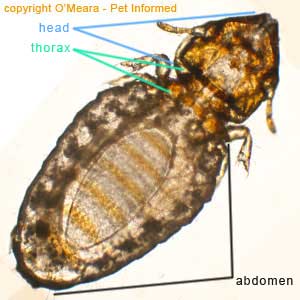

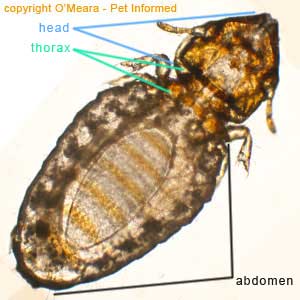

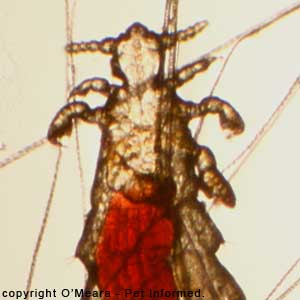

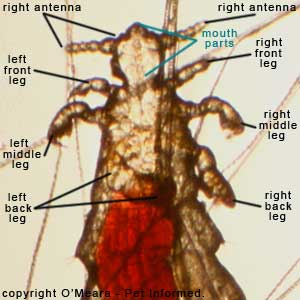

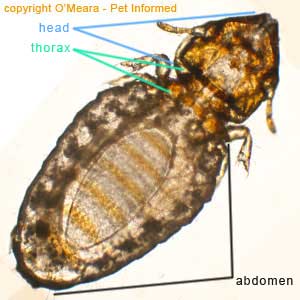

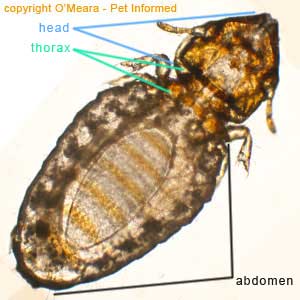

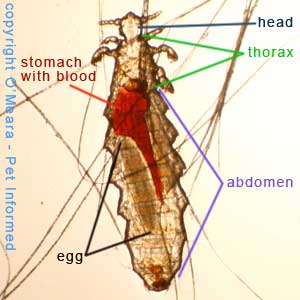

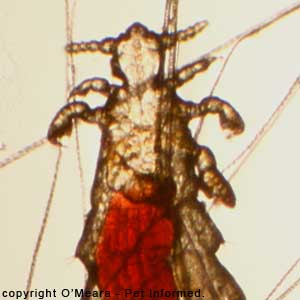

Lice pictures 20, 21 and 22:

Lice pictures 20, 21 and 22: These are images of the cat biting-louse species:

Felicola subrostratus,

taken through the microscope. This louse pictured is an adult female and she has an egg inside of her, waiting to be laid.

Like most lice, the body of this cat louse is white to very pale

yellow in colour (it appears slightly banded), with a darker orange-tan to brownish-coloured head. The feline louse pictured, like all other lice, has a dorso-ventrally flattened, pancake-like shape (it looks as though it has been squashed from above).

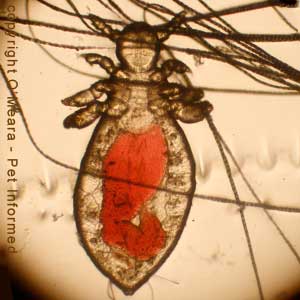

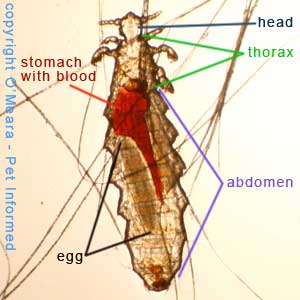

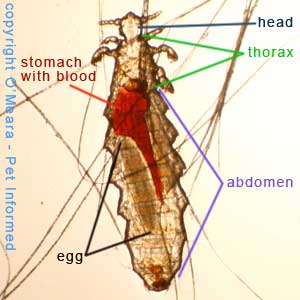

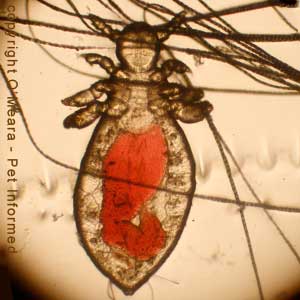

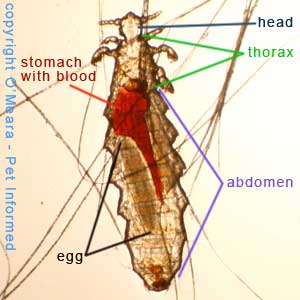

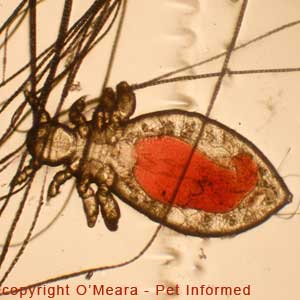

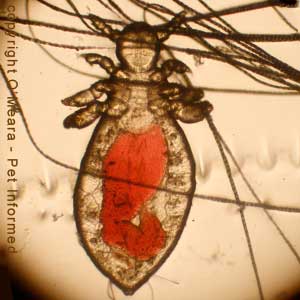

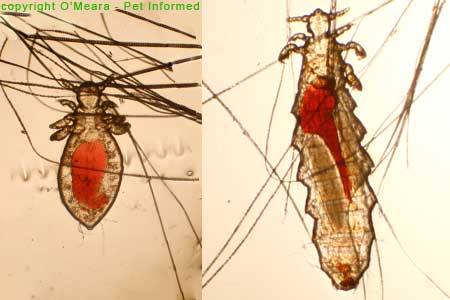

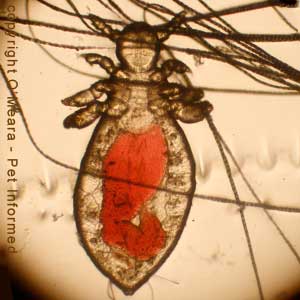

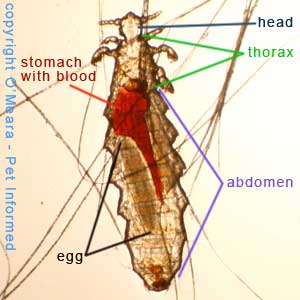

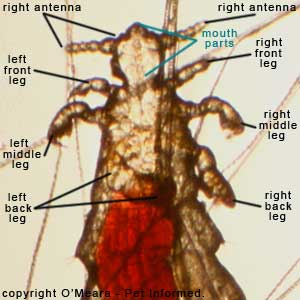

Lice pictures 23, 24 and 25:

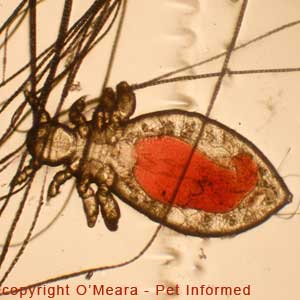

Lice pictures 23, 24 and 25: These are images of the mouse sucking-louse species:

Polyplax serrata,

taken through the microscope. The first picture (lice photo 23) is of a juvenile louse stage called a

nymph. The second louse pictured (lice pictures 24 and 25) is an adult female and she has an egg inside of her, waiting to be laid.

Like most lice, the body of this mouse louse is white to very pale

yellow in colour. The stomach of this mouse louse (adult or nymph) appears bright red

under the microscope because this species of louse is a

sucking louse and it feeds

upon the red blood of its mouse host. The murine (mouse) louse pictured, like all other lice, has a dorso-ventrally flattened, pancake-like shape (it looks as though it has been squashed from above).

Lice have three main body parts: a head, a thorax and an abdomen (these have been labeled in lice pictures 22 and 25) and, like most other insects, lice have six legs (three on each side) that originate from the

underside of the mid-section of the body (thorax). Unlike many other insects, lice have no wings and do not fly. Lice move from host to host and from host to environment to host by direct host contact (lice infested hosts brushing up against non-infested hosts)

and through direct contact with lice or nit infested bedding, brushes, nesting sites, paddocks, yards and blankets.

Lice are mobile, but do not move at high speed.

There are two main

Orders or groupings of lice:

Mallophaga (the chewing lice or biting lice group) and

Anoplura (the blood sucking lice group). The two louse Orders can be identified by the width of their heads relative to the width of their thoraxes and, less reliably, by the size of their legs. Chewing or biting lice, like

Felicola (lice picture 26, below), have a large, often-triangular, head that is bigger and wider than the width of their thorax, whereas sucking lice (louse picture 27, below) have a small head, that is narrower than the width of their thorax. Sucking lice tend to have enormous, strong, well-developed legs and claws for gripping their host's fur very tightly, whereas biting lice tend

to have very small, comparatively weaker, legs and claws. Biting lice hang on to their host's fur or feathers

with their strong, chewing mandibles much of the time and so probably don't need highly developed legs for

grasping the coat or plumage of their hosts.

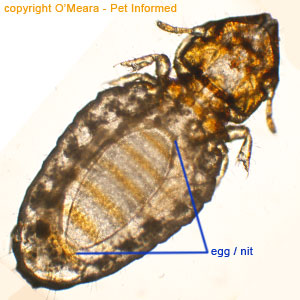

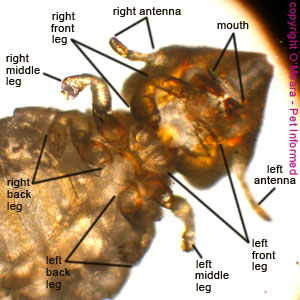

Lice picture 26:

Lice picture 26: This is an image of a feline biting louse. The triangular head of the biting louse is

wider

than the width of the louse's thorax and the legs of the biting louse are small and weak compared to

those of the sucking louse (louse photo 27). Notice that there is no blood inside of the biting louse's stomach (no red central region). This is because it does not feed on blood, but on dander and skin flakes, instead.

Lice picture 27: This is a photo of a murine (mouse) sucking louse. The head of the sucking louse is

narrower than the width of the louse's thorax and the legs of the sucking louse are large and strong compared to those of the biting louse (lice pic 26). Notice that there is red blood inside of the sucking louse's stomach

(red centre). This is because this louse feeds upon the blood of the host animal.

Once the Order of the louse has been identified as being of either the biting louse variety or

the sucking louse variety, then the basic Genus of the louse is generally very easy to determine,

based upon the species of the host that the louse was found upon. Lice are very host specific and will generally

never cross host species. Most species of animal host (aside from cattle, dogs and guinea pigs) have

only one Genus of biting lice and one Genus of sucking lice that infests them and so, once

the Order of the louse has been identified, it is usually very simple to determine the Genus of the louse parasite based on the species of host it was found upon. For example, horses have two kinds of lice - a biting louse species called Damalinia equi and a sucking louse species called Haematopinus asini. Sheep have several species of sucking lice that infest them, but all are of the same Genus: Linognathus (Linognathus ovillus, L. pedalis and L. africanus). Sheep also have one species of biting louse called Damalinia ovis. Even more conveniently, some species of host animal only have a single species of louse (either a sucking or a biting louse variety) that infests them and so it is, thus, very easy to determine the species of the louse just by identifying that the insect in question is a louse. For example, mice have only one kind of louse - a sucking louse called Polyplax serrata and cats have only one kind of louse - a chewing louse called Felicola subrostratus. In the case of birds, there are no Anopluran (sucking lice)

varieties - birds only have Mallophagan chewing or biting lice species parasitising their feathers.

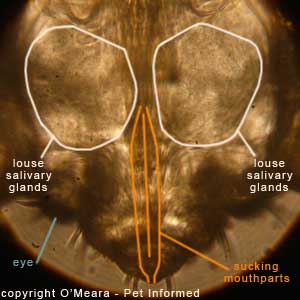

THE HEAD OF THE LOUSE:

The head of the louse is small and simple with two eyes; a pair of basic, segmented antennae and

specialized mouth-parts designed for either sucking the host animal's blood (in the case of Order Anoplura - the sucking lice) or biting the host animal's skin (in the case of Order Mallophaga - the biting lice).

As mentioned previously, the size and width of the louse's head relative to the width of its thorax is important to the determination of the Order that the louse comes from. Biting or chewing lice (Order Mallophaga), like Felicola (louse image 28, below), have a large, often-triangular, head that is bigger and wider than the width of their thorax, whereas sucking lice (Order Anoplura) have a small head that is narrower than the width of their thorax. The mouthparts are also important in determining whether a louse is of a sucking or a biting variety. Biting lice have enormous, grinding, toothed mandibles for hanging onto their host's feathers and fur shafts

and for eating their host's skin materials (e.g. dander, feather keratin). Sucking lice have thin, retractable, elongated, tube-like mouthparts, which are inserted through the host animal's skin to facilitate the consumption of blood.

Lice pictures 28 and 29: These are both photographs of biting louse species. The louse on the

left is Felicola, the cat louse (feline louse). The louse on the right is Damalinia equi, the biting louse of the horse. Their heads differ in shape from one another (Damalinia's is more rounded, Felicola's

is triangular), but both lice have the broad head (wider than the thorax) that is typical of the Order Mallophaga. The structures protruding from the sides of the insects' heads in these lice pictures are their antennae.

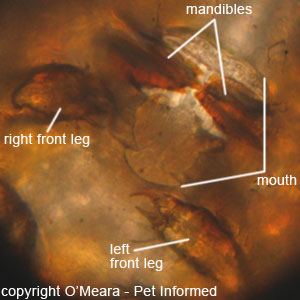

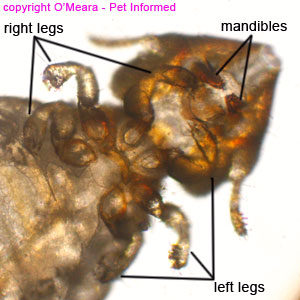

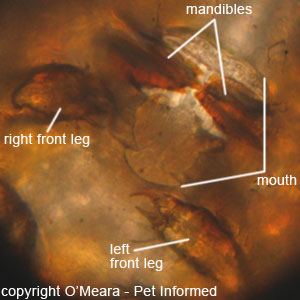

Lice pictures 30 and 31: These are microscope photographs of the feline biting lice, Felicola,

taken from beneath the insect's body. The six legs of the insect, protruding from beneath the thorax,

are clearly visible in these lice pictures, as are the biting mouthparts (indicated in image 31).

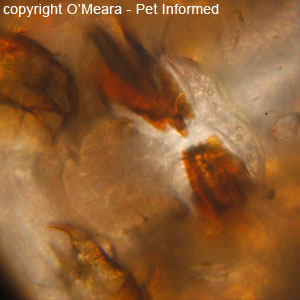

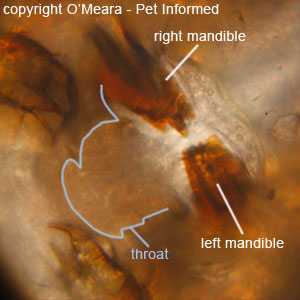

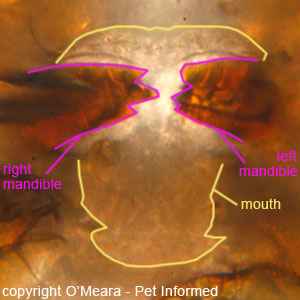

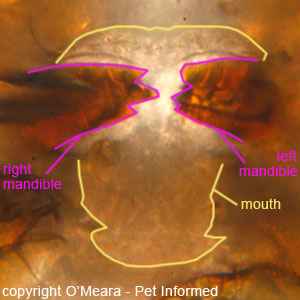

Pictures of lice 32 and 33: These are close-up microscope photographs of the mouth-parts of a biting louse (Felicola). The mouth has two chewing mandibles (one on each side) with three-pronged teeth on each mandible.

These mandibles move in and out in a guillotine-like chewing action. These mouthparts help the louse to hold on tightly to the animal's hairs and feathers and they also help the louse to grind down the keratin and dander materials of the host animal's skin into sizes that are small enough for the

insect to ingest. The clawed front legs of the chewing louse can also be seen in these images (labeled) and these may help to hold and feed food (dander, keratin flakes, scale and so on) into the louse's mouth.

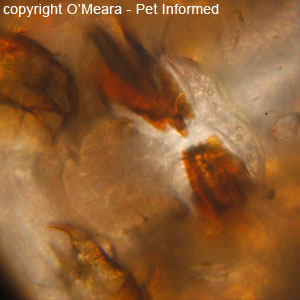

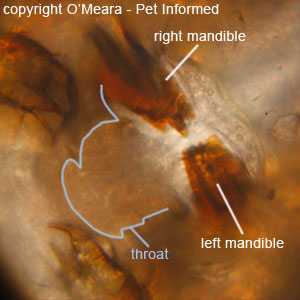

Lice pictures 34 and 35: These are some more close-up microscope photographs of the mouth-parts of a biting louse.

Biting lice pictures 36 and 37: And, because we can, here are some more close-up microscopic photos of the mouth-parts of a biting louse. The outline of the mouth has been labeled in image 37 of these lice pictures.

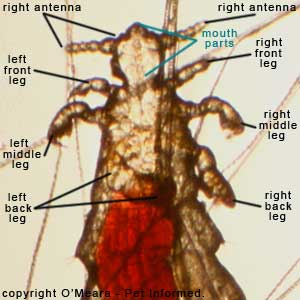

Lice pictures 38 and 39: These are microscope photographs of the mouse sucking lice, Polyplax serrata,

taken from above the insect's body. The six legs of the insect, protruding from beneath the thorax,

are clearly visible in these lice pictures, as are the biting mouthparts (indicated in image 39), visible through the translucent head.

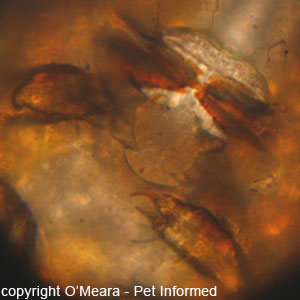

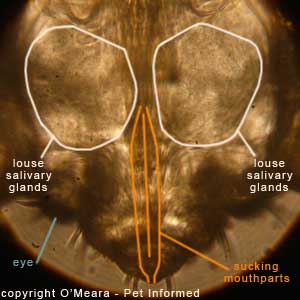

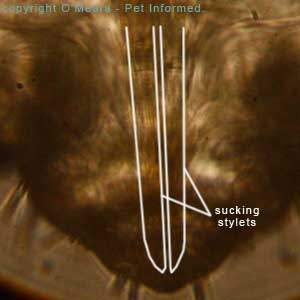

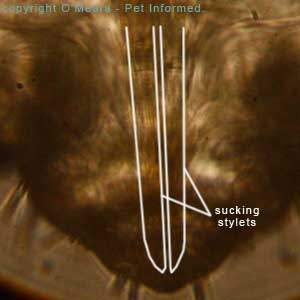

Pictures of lice 40 and 41: This is an extreme close-up view of the head of the mouse

louse, Polyplax serrata. Polyplax is a sucking lice species of louse. The tip of the louse's nose is at the bottom of these lice pictures.

The louse picture shows the elongated, tubular mouthparts (termed stylets) of the louse,

which the louse inserts through the host animal's skin, like straws, in order to drink its blood. There are three stylets. When the sucking louse is not in the process of feeding (like in these lice pictures), the long, straw-like stylets are retracted high up inside of the louse's head, out of sight. We can only see them

in this picture because the louse's head is transparent and see-through. The photo also shows the enormous salivary glands that are present in this insect.

Lice pictures 42 and 43: This is an even more extreme close-up view of the tubular mouthparts

of the sucking louse (stylets). They are elongated and slightly banded in appearance.

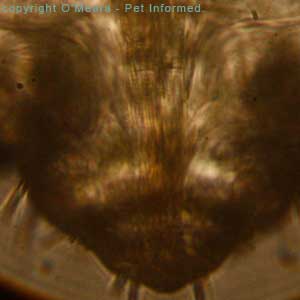

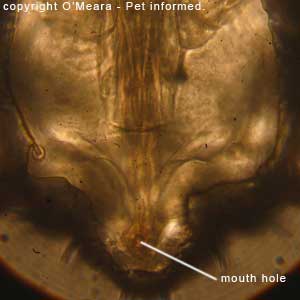

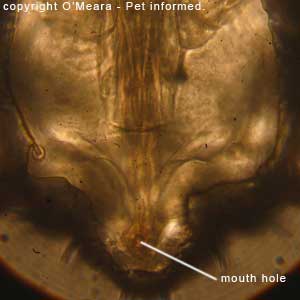

Lice pictures 44 and 45: In this louse picture, the microscope has been carefully focussed upon

the skin surface at the bottom (ventrum) of the louse's head. A tiny hole can be seen in the skin (labeled in picture 45). This tiny hole is the louse's mouth! When the louse wants to drink the host animal's blood,

it protrudes its straw-like stylets out through this mouth hole and into the host animal's skin.

THE THORAX OF THE LOUSE:

The thorax is the central (middle) section of the insect body. It is where the legs and wings (if present)

of the insect arise from. In the case of the louse insect, there are no wings: only legs arise from beneath this thoracic mid-section region. The louse's legs are specially clawed and shaped for gripping the host animal's fur or feather shafts.

In the case of the sucking louse (Anoplura), the legs and gripping claws (feet) are exceptionally strong and large in size, compared to the size of the louse's body, and the feet are specially modified for grasping the hairs of the host animal's pelt. The size and span of the sucking louse's claws is possibly dependent upon the diameter of the hair shaft that the individual sucking louse species has been designed to infest. For example: sucking louse varieties on cattle and horses have very large claws to better grip the very wide hairs present on these animals' coats. The sucking louse probably needs such large, strong claws because it has no strong mandibles to help it to cling onto the host animal's hairs.

The biting louse (Mallophaga), in contrast, has rather small, weak-looking legs compared to those of the sucking louse. The biting louse's huge, grasping mandibles probably more than make up for this lack of limb strength.

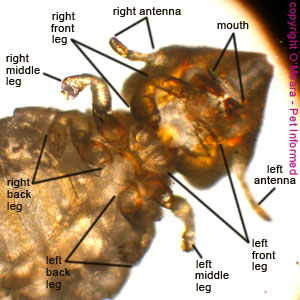

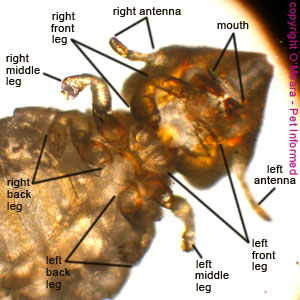

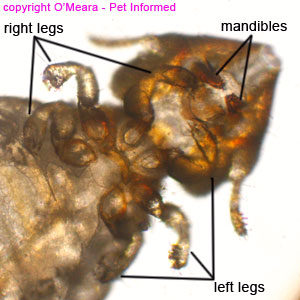

Chewing lice pictures 46 and 47: These are photographs of the feline biting louse, Felicola,

taken from beneath the insect's body. The six legs of the insect, protruding from the thorax,

are clearly visible in these lice pictures, as are the biting mouthparts. The claws are pincer-like for gripping hairs.

Chewing lice pictures 48 and 49: These are close-up photographs of the head and thorax of

the cat chewing louse, Felicola, taken from beneath the insect's body. The six legs of the insect, protruding from the thorax, are clearly visible in these lice pictures, as are the biting mouthparts. All of these lice anatomy parts have been labeled. The claws are pincer-like for gripping hairs.

Chewing lice picture 50: This is a close-up photograph of the right side of the head, thorax

and abdomen of the equine biting louse, Damalinia equi, taken from above the insect's body. The right middle and rear legs of the insect, protruding from the thorax, are clearly visible in this lice picture. The claws are small and pincer-like for gripping hairs.

Chewing lice pictures 51: This is an extremely close-up photo of one of the right legs of the horse biting louse, Damalinia, taken from above the insect's body. The hairy feet and

pincer like claws are visible.

Sucking lice picture 52: This lice photo is a close-up photograph of the head and thorax of

the mouse sucking louse, Polyplax, taken from above the insect's body. The six legs of the insect, protruding from the thorax, are clearly visible, as are the tubular, sucking mouthparts. All of these lice anatomy parts have been labeled. The legs and claws are very large

and strong, for gripping the hairs of the host animal.

Sucking lice pictures 53: This louse image is a photograph of a sucking louse nymph.

The image clearly illustrates the large, strong legs of the sucking louse group.

Sucking lice pictures 54: This is a close-up photograph of the head and thorax of

the mouse sucking louse, Polyplax, taken from above the insect's body. The louse's head

is pointing downwards in this photo. The image clearly illustrates the large, strong claws (labeled) present on the legs of the sucking louse types.

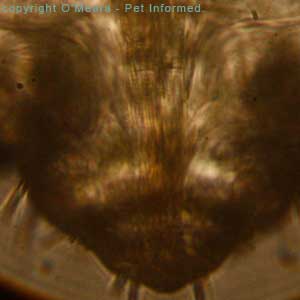

THE ABDOMEN OF THE LOUSE:

The abdomen is the hind-most (rear-most) section of an insect's body. It is generally the largest section of

the insect body (i.e. it is bigger than the head or thorax parts). The abdomen contains the insect's reproductive and digestive organs as well as the series of air-filled tubules that make up the insect's respiratory system. Eggs grow and mature in the female louse's abdomen before they are laid on the animal's fur.

Louse photo 55: This is a photo of the cat louse, Felicola. It is a biting louse. The abdomen of the

louse is the large rear section, behind the thorax and legs. The abdomen contains an egg or nit in this individual, which will be soon laid. There are no wings. The stomach of this feline louse is not red because this species does not feed upon the blood of the

host animal.

What does lice look like 56: This is a photograph of the horse biting louse, Damalinia.

The abdomen of the louse is the large rear section, behind the thorax and legs. There are no wings.

What do lice look like 57: This is a photo of the mouse louse, Polyplax serrata. It is a sucking louse. The abdomen of the louse is the large rear section, behind the thorax and legs. The abdomen contains an egg or nit in this individual, which will be soon laid. There are no wings. The stomach of this mouse louse appears bright red under the microscope because this species of louse is a sucking louse and it feeds upon the red blood of its mouse host.

What do lice look like 58: This is a photo of the mouse louse, Polyplax serrata. The individual pictured is a nymph stage. The abdomen of the nymph louse is the large rear section, behind the thorax and legs. There are no wings. The stomach of this mouse louse appears bright red under the microscope because this species of louse is a sucking louse and it feeds upon the red blood of its mouse host.

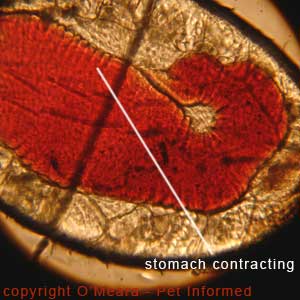

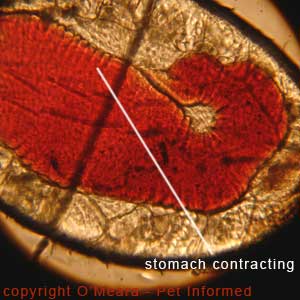

What does lice look like 59: This is a close-up photo of the stomach of the blood sucking

louse in image 58 (nymph). It is red and full of blood. Notice the ripples in the stomach wall (indicated).

These are peristaltic waves (contractions) of stomach wall muscle movement - the louse's stomach wall

is contracting and moving as it digests its blood meal. I just like the photo - it shows us how, despite

their tiny size, insects are fully formed creatures with organs every bit as complex as those of much

larger animals.

5) Lice infestation in different domestic animal species.

This section contains detailed photos and information (including lice treatment information) about lice and louse infestation

in different animal species. It is designed as a pictorial guide to help owners and farmers

to identify lice infestations in their pets and livestock. To date, Pet Informed only has photos of lice in horses, goats (also sheep), cats and mice. Lice pictures pertaining to various other domestic, avian and livestock animal species will appear in this section as they become available.

5a) Horse lice (horse louse) - equine louse information and treatment:

Lice tend to infest horses most commonly during the seasons of Winter and Spring, however, they can be present all year 'round if conditions are favourable. Lice on horses do not come from sheep, goats, cattle, camels, alpacas or any other livestock animals, but from other horses and are spread from horse to horse through direct body contact (e.g. horses housed close together)

and through the sharing of louse and nit infested rugs, brushes and combs. Eggs, nymphs and adult lice which

are rubbed off onto yards, posts and trees in a paddock, can also potentially be collected by other

horses that happen to come by and rub their bodies up against the same spot/s.

Lice parasites can infest any region of the horse's skin, but heavy infestations will

tend to accumulate around the poll, mane, withers, lateral neck and tail base of the animal. These are the areas of the horse's coat that owners will need to search through most carefully when suspecting of lice on their animal/s. Although most horses affected with lice will have only mild to moderate infestations

of the insects, enough to cause annoyance, restlessness and coat damage, but nothing more, some horses will develop severe infestations of lice (see the images below), which can potentially become health-threatening. Those horses which are prone to heavy infestations

of lice tend to be those that are already debilitated or neglected in some way. Horses that

are starved or malnourished, wormy, thin, over-crowded, aged, ill, stressed and otherwise neglected

are prime candidates for severe lice.

Horses are infested with two main kinds of lice: a biting louse variety called Damalinia equi and

a sucking louse variety called Haematopinus asini. Heavy infestations of sucking lice are

able to cause severe anaemia in their equine hosts and severely infested and weakened horses (especially old horses) can potentially die as a result of their infestation. Note, however, that death from

louse infestation is very uncommon and is generally contributed to by the kinds of adverse living conditions

that caused the lice to proliferate in the first place: starvation or malnutrition, neglect, stress, inclement weather, over-crowding, poor housing and severe age or pre-existing illness. Damalinia equi is the biting louse variety seen on horses. It does not tend to cause anaemia or

severe life-threatening debility, however, it does tend to irritate the horse hosts to a significant

degree (a trait it shares with the sucking lice - which are also very itchy). Biting and/or sucking louse-infested horses spend a good deal of their time scratching and biting at the insects in the coat, which results in damage to the hair coat and skin. The intense itchiness can result in reduced time spent grazing, which can result in the animal becoming thin (ill-thrift) and unhealthy.

Lice Treatment - Getting Rid of Lice in Horses:

Horse lice infestations can be treated with powders, rinses, dips or sprays that contain

pyrethrins, carbaryl, rotenone, coumaphos and other similar ingredients. There are many commercially available horse products designed for the purpose of getting rid of lice in horses - visit a veterinarian or your local stockfeed supplier for more advice on which products to use.

Please note that coumaphos and carbaryl are organophosphate and organophosphate-like chemicals with a high potential for toxicity in animals and people. If used, products

containing these active ingredients must be applied very carefully, according to the strict instructions on the product label. Owners are advised to take appropriate safety precautions when using such insecticide products (i.e. only use the products in a well-ventilated place; wear gloves when using the products; consider wearing breathing apparatus

when using the products, especially if they are aerosolized products and so on). Owners are

also advised to be aware of and to take appropriate environmental precautions

when using such insecticide products, including pyrethrins (i.e. make sure there is no risk of any pesticide washing into waterways or groundwater supplies and so on). Debilitated horses should not be bathed in coumaphos or carbaryl and horses should not be allowed to consume coumaphos- or carbaryl-containing

products.

Products that kill lice in horses (those available in Australia):

Bay-O-Pet Asuntol Dog and Horse Rinse (active ingredient: coumaphos).

G-Wizz Insecticidal Block (active ingredient: carbaryl).

Pestene (active ingredients: sulfur, rotenone).

Y-Itch Medicated Lotion (active ingredients: sulfur, lanolin, menthol, carbaryl, camphor).

Because unhatched louse eggs are not killed by such insecticide products and will hatch out within a week or so of product

application, the chosen louse treatment needs to be reapplied in 7-10 days to kill off any newly emerged

nymphal lice that will have hatched since the previous application.

All horses that have been in contact with the infested horse/s or horse yards, even if they do not appear to be infested, should be treated. Brushes and horse rugs and other fomites that could spread lice from host to host should also be treated to ensure that these are not allowed to remain as sources of reinfestation. Yards (e.g. fences, horse stalls, stables, wood panels, trees) can harbor lice for weeks to months and should be depopulated of all equine hosts for a period of time (at least 2 months to be safe) to ensure that freshly-treated horses are not soon reinfested by their environment.

Failure to achieve control of horse lice problems suggests that:

1) the treatment used was not appropriate - i.e. the wrong product was used, an out-of-date product was used, a badly stored, inactive product was used and so on;

2) the treatment used was not applied correctly - i.e. the product was not applied to the whole coat (leaving some lice populations alive and able to breed), the product was not reapplied in 2 weeks to kill the newly-hatched lice,

some of the horses in the population did not get their lice treatment and so on and

3) there could be a significant source of louse reinfestation remaining - i.e. maybe there is a louse-infested reservoir horse in contact with the treated animals, maybe there are lice in the environment, the horse brushes, the horse rugs and so on.

Equine lice picture 60: This is a picture of a horse with a severe louse infestation. Notice how the horse's fur appears moth-eaten and patchy? The loss of fur is the result of the horse scratching itself up against trees and fences in an attempt to relieve the itchiness of the parasites' lice bites. This particular horse was very old, thin and crippled: a stressed, debilitated state that facilitated the multiplication of the insect pests.

Horse lice pictures 61 and 62: These are close up photographs of the coat of the lice horse in image 60. The horse's coat is coarse and rough and of poor quality and bears many patches of thinly-haired to

hairless bald spots, where the horse has broken the hair shafts scratching and rubbing itself up against trees and fences in an attempt to remove the lice infestation. Chronically damaged hair and skin can change colour and the hairs may grow back paler or darker in shade.

Horse lice photos 63, 64 and 65: These are pictures of some adult lice hanging onto the long hairs of the horse's outer coat. The adult lice are the whitish-coloured insects clinging

to the hairs. Being in such an open position, these lice are perfectly placed

to infest the coats of any other horse hosts that happen to brush alongside this louse infested animal. These lice pictures show that, with a thorough inspection of the horse's coat, horse lice are not all that hard to find.

Take a closer look at lice picture 65 (the third louse picture in this grouping). It is a close-up

image of lice photo 64. Notice how the body or abdomen of the louse (pointing downward) is white and

oval shaped. Then notice the louse's head (pointing upwards) - it looks like a broad, brown-red triangle

sitting on top of the louse's body. The thorax (small and narrow) is hard to discern, but sits just between

the head and the abdomen. The large, broad, triangular-shaped head tells us that this is a biting louse (also called chewing lice) variety and that, as such, it is likely to be of the Order: Mallophaga and of the Species: Damalinia equi.

Pictures of lice 66 and 67: These are images of a severe louse infestation on a horse's coat.

The adult lice are about 1-2mm long with large, pale bodies and darker coloured (reddish) heads. The lice eggs

or nits are long, narrow, white, rice-grain-like structures attached to the hair shafts of the horse's coat.

When the fur of the horse was parted, particularly in the areas of the coat under the mane, alongside the neck and around the withers, poll and tail-base, clusters of lice and lice eggs (lice nits)

could be found at the base of the hairs. These images show what this severe lice infestation

looked like and what you might look for when trying to diagnose lice infestation on a horse. The adult lice are

positioned against the horse's skin, head down and bottom-up, chewing on the dander. Further up the hairs, small lice nits or eggs (which look like white grains of rice) can also be seen.

What is lice - picture 68: This a microscope image of the horse lice species, Damalinia equi. It is a biting louse species. Horses also have a species of sucking louse called Haematopinus asini (Pet Informed

does not yet have a photo of this louse species).

Photos of louse egg 69: This is an image of a louse egg or nit attached to the hair shaft of

a horse. The louse egg pictured has a blunt end (it looks cut-off) indicating that it has hatched already. Non-hatched eggs are usually rounded at each end.

5b) Feline lice (cat louse) - cat lice treatment and information:

Lice tend to infest cats most commonly during the seasons of Winter and Spring, however, they can be present all year 'round if conditions are favourable. Lice on cats do not come from dogs or rodents or livestock, but from other cats and are spread from cat to cat through direct body contact (e.g. cats housed close together)

and through the sharing of louse and nit infested rugs, bedding, housing, carry boxes, brushes and combs.

Eggs, nymphs and adult lice which are rubbed off onto cages, cat runs and cat aviaries can also potentially be collected by other

cats that happen to come by and rub their bodies up against the same spot/s.

Cats are infested with only one kind of lice: a biting louse variety called Felicola subrostratus. Most of the cat lice infestations that I have seen have been in outdoor, stray, feral or wandering cats,

which have most likely been in contact with other free-living, lice infested cats. Lice are not a common finding in pet cats unless they have been outside a lot (e.g. farm cats, cats with access to feral cats);

have recently gone missing (i.e. have spent time roaming) or have spent time in a large, multiple-cat facility or multi-cat household (e.g. a cattery with high opportunity for cat-to-cat contact, an animal shelter or a pound). Indoors-only cats very rarely have this parasite.

Of those cases of feline lice infestation that I have seen, most of them tend to only be very mild, with but a few lice found here and there on the animal's coat. It often takes a good deal of careful hunting to find adult lice and nits on a cat's coat and suspicious cat owners need to be very thorough in their search for them. The reason for the very low numbers of lice found on cats has probably got a lot to do with the cat's fastidious grooming habits. Many of the adult and nymphal lice probably get licked up and consumed by the cat as it grooms and nibbles itself

in response to the itchy bites of the insects. Overgrooming and scratching is one of the main

signs of lice in the cat and cats may become secondarily afflicted with furballs as a result of

this overgrooming and hair consumption. Severe cases of lice do occur in some cats and are most commonly seen in already-debilitated and/or older cats who have been unable to groom very well.

Lice Treatment - Getting Rid of Lice in Cats:

Cat lice infestations can be treated with powders, shampoos, rinses or sprays containing

pyrethrins, rotenone, maldison, carbaryl and other similar ingredients.

There are many commercially available cat products designed for the purposes of getting rid of lice in cats - visit a veterinarian for more advice on which products to use. The most important

thing is to make sure that the lice product you choose is specifically designed for and safe for cats.

Please note that maldison and carbaryl are organophosphate and organophosphate-like chemicals with a high potential for toxicity in animals and people. Similarly, some pyrethrins

can be toxic to certain cats. If used, products containing these active ingredients must be applied very carefully, according to the strict instructions on the product label. Owners are advised to take appropriate safety precautions when using such insecticide products (i.e. only use the products in a well-ventilated place; wear gloves when using the products; consider wearing breathing apparatus

when using the products, especially if they are aerosolised products and so on). Owners are

also advised to be aware of and to take appropriate environmental precautions

when using such insecticide products, including pyrethrins (i.e. make sure there is no risk of any pesticide washing into waterways or groundwater supplies or contaminating sensitive ecologies and so on). Debilitated cats should not be bathed in maldison or carbaryl or pyrethrin and cats should not be allowed to consume these products.

Products that kill lice in cats (those available in Australia):

Frontline Top Spot Cat.

Frontline Spray.

Coalfoam (active ingredients: coal tar, pyrethrin, piperonyl, carbaryl).

Di-Flea Flea and Tick Rinse and Yard Spray (active ingredients: maldison).

Di-Flea Puppy and Kitten Insecticidal Shampoo (active ingredients: pyrethrin, piperonyl).

Fido's Fre-Itch CPP Flea Powder (active ingredients: pyrethrin, piperonyl, carbaryl).

Fido's Fre-Itch Flea Powder (active ingredients: carbaryl).

Fido's Fre-Itch Flea Shampoo (active ingredients: carbaryl).

Fido's Fre-Itch Pyrethrin Shampoo (active ingredients: pyrethrin, piperonyl).

Malaban Wash Concentrate (active ingredients: maldison).

Malatroy (active ingredients: maldison).

Musca-Ban (active ingredients: pyrethrin, piperonyl).

Pestene (active ingredients: sulfur, rotenone).

Petgloss Shampoo (active ingredients: pyrethrin, piperonyl).

Quick-Kill Rinse Concentrate for Fleas, Ticks and Lice (active ingredients: pyrethrin, piperonyl).

Sectalin Insecticidal Shampoo (active ingredients: pyrethrin, piperonyl).

Because unhatched louse eggs are not killed by such insecticide products and will hatch out within a week or so of product

application, the chosen louse treatment needs to be reapplied in 7-10 days to kill off any newly emerged

nymphal lice that will have hatched since the previous application.

All cats that have been in contact with the infested cat/s or cat environments, even if they do not appear to be infested, should be treated for lice. Brushes, bedding, rugs, cat boxes and other fomites that could spread lice from host to host should also be treated to ensure that these are not allowed to remain as sources of reinfestation. Cat yards (e.g. cat aviaries and cat runs) can harbor lice for weeks to months and should be depopulated of all feline hosts for a period of time (at least 2 months to be safe) to ensure that freshly-treated cats are not soon reinfested by their environment.

Failure to achieve control of cat lice problems suggests that:

1) the treatment used was not appropriate - i.e. the wrong product was used, an out-of-date product was used, a badly stored, inactive product was used and so on;

2) the treatment used was not applied correctly - i.e. the product was not applied to the whole coat (leaving some lice populations alive and able to breed), the product was not reapplied in 2 weeks to kill the newly-hatched lice,

some of the cats in the population did not get their lice treatment and so on and

3) there could be a significant source of louse reinfestation remaining - i.e. maybe there is a louse-infested reservoir cat in contact with the treated animals, maybe there are lice in the environment, the cat brushes, the cat bedding, the cat boxes and so on.

Lice pictures 70: This is an image of the cat louse, Felicola.

Case Study - Severe Lice Infestation in a Cat:

As I have mentioned before, severe, overwhelming infestations of lice (and other parasites) can sometimes be

an indication of underlying disease or severe physiological stress (e.g. malnutrition, bullying, inclement weather and so on). The following case (a stray, louse infested cat brought into our clinic)

is a prime example of this.

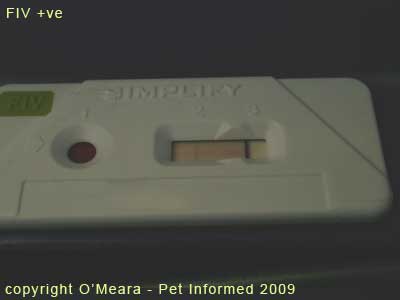

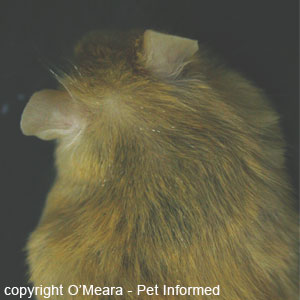

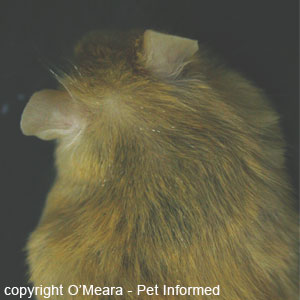

Cat lice picture: This entire, male, ginger tom cat was brought into the vet clinic

after being trapped by rangers in a reserve. He was skinny and unhealthy, with a large burst

abscess on the side of his face (the blood you can see on the right ear).

Cat lice pictures: Examination of the cat's fur revealed hundreds of lice insects

and their eggs (nits). These are the pale yellow dots with the dark-brown heads that you can

see all through the fur.

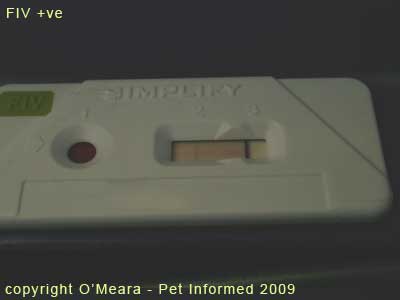

Picture A: As the cat had such a severe lice burden and appeared so unwell, an

underlying disease condition was suspected. This cat was tested for FIV (Feline Immunodeficiency Virus

or Feline AIDS), a common immunosuppressive virus in our local feral cat populations,

and found to be positive. It is unknown whether the virus per se was the exact cause of the

cat's debilitated, lousey condition (cats can carry FIV without symptoms for a variable period of

time) or whether it was just the cat's severe malnutrition, stress and exposure to extreme

weather (the cat was caught at the end of winter) that caused it to become so susceptible to the parasites.

Picture B: Frontline was applied to the fur to kill the lice and make the cat more comfortable.

5c) Mouse lice (murine lice) - mice lice treatment and information:

Mice are infested with only one kind of lice: a sucking lice variety called Polyplax serrata.

Rodents like mice and rats and guinea pigs are prone towards severe infestations of lice because they are often purchased from overcrowded, unhygienic, high-lice-transmission, unsavoury breeding situations (e.g. irresponsible breeders); they are often housed close-together in high numbers

(facilitating mouse-to-mouse transmission of lice) and rodent pet owners often don't examine the fur of their charges

all that closely. Lice infestation can sometimes cause havoc in laboratory mice facilities too.

Heavy infestations of sucking lice are able to cause severe anaemia in their murine hosts and severely infested and weakened mice (especially old mice) can potentially die as a result of their infestation. Mouse lice bites are also very itchy and some mice

will literally tear their fur from their bodies, leaving behind big patches of baldness. Some itchy mice will even scratch their skin to the point of outright bleeding, leaving behind big sores and scabs on the skin. This kind of severe itching and self trauma can be one of the signs of lice that owners might recognise first in their mice and should be a clue for owners to have a close look at their pet's coat for lice or nits. Although living mouse lice can be tricky to sight, their nits are usually easy to spot in mouse fur (see images below) with a careful search.

Products that kill lice in mice (those available in Australia):

Pyrethrin 0.05% shampoo - shampoo once a week for up to 4 weeks.

Carbaryl 5% powder - dust lightly once a week for 2-3 treatments.

Revolution(?) - according to one of my colleagues, a single, tiny drop of Revolution

once a fortnight over a couple of treatments can treat sucking lice in mice and rats. Please note that this is strictly off-label use (we can not take responsibility for any

side effects that might occur) and overdosing could produce toxicity. We tried it in some of our lousy mice and they have been fine so far ...

All mice that have been in contact with the infested mouse/mice or rodent environments, even if they do not appear to be infested, should be treated for lice. Brushes, bedding, rugs, mouse boxes and other fomites that could spread lice from host to host should also be treated to ensure that these are not allowed to remain as sources of reinfestation. Mice hutches (e.g. mouse aquariums, cages, aviaries and enclosures) can harbor lice for weeks to months and should be depopulated of all murine hosts for a period of time (at least 2 months to be safe) to ensure that freshly-treated mice are not soon reinfested by their environment.

Pictures of lice 71 and 72: These lice pictures show a mouse with a moderate to severe

lice infestation. The fur of this mouse still looks quite good - there are no bald spots or places on the skin that

have been heavily traumatised through the rodent's scratching and excessive grooming activities. In the more magnified image (lice picture 72), the lice eggs or nits can now start to be seen on the mouse's fur as

chains of white ovals located along the shafts of a few of the hairs.

Mouse lice pictures 73, 74 and 75: This is the same louse infested mouse as that pictured in the images above. The lice nits can be clearly seen in image 73, as white, elongated objects that have been laid along the hair shafts of the mouse's fur. Lice photo 73 has been magnified in lice picture 74 and a couple of

the louse nits have been labeled for you. In louse photo 75, a heavily infested region of the

mouse's coat has been photographed - if you look very closely, you should be able to see

many lice eggs located all through the layers of the mouse's fur.

Pictures of lice 76, 77 and 78: This is another mouse with a severe louse infestation. Lice eggs were found on the hairs of this mouse, similar to the tan mouse above. The photos of this mouse were included because they illustrate the severe scratching and self-trauma that can occur as a result

of lice infestation. This mouse had literally torn the fur from its body (notice the bald spots)

and had scratched its skin to the point of bleeding, leaving behind big sores and scabs on the skin. This severe self trauma can be one of the signs of lice that owners might recognize first

in their rodent pets - scratching and skin trauma should be a clue for owners to have a close look through their pet's coat for lice or nits.

Lice picture 79: This is a photo of a mouse louse nymph.

Lice photo 80: This is a photo of a mouse louse adult. The species of louse is Polyplax serrata.

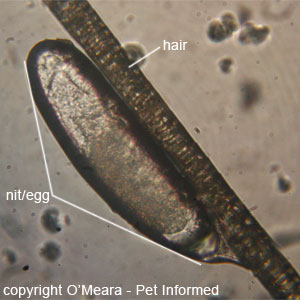

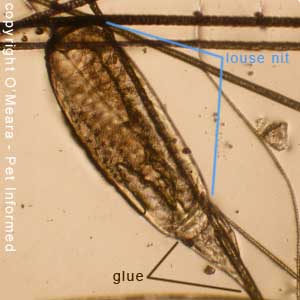

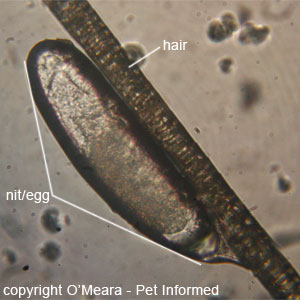

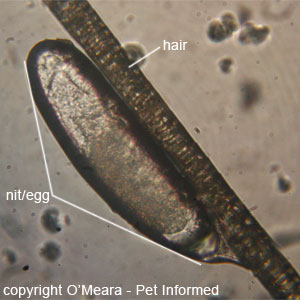

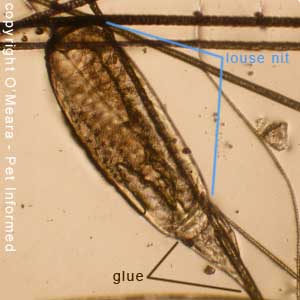

Lice nits pictures 81 and 82: These are microscope photos of a louse egg (louse nit) that is attached to a shaft of the mouse's hair. The egg is rounded on both ends, indicating that it has not yet hatched out.

Lice picture 83: This is another image of a mouse louse egg (louse nit) that is attached to a shaft of the mouse's hair. The adult louse glues the egg to the host's fur using a special adhesive from her own body - this "glue" has been labeled in this picture.

Louse egg picture 84: When this particular egg hatched, the newly emerging nymph burst out through

the side of the egg, not out through the top. This left a large rent (hole) down the side

of the egg casing.

5d) Goat lice (caprine lice) - goat lice treatments and information (also includes sheep lice treatment info):

Lice tend to infest sheep and goats most commonly during the seasons of Winter and Spring, however, they can be present all year 'round if conditions are favourable.

Lice on sheep do not come from goats, cattle, camels, alpacas or any other livestock animal species, but from other sheep

and are spread from sheep to sheep through direct body contact (e.g. sheep housed close together or sheep running side-by-side in a flock) and through the sharing of louse and nit infested rugs, shearing equipment, brushes and combs. Likewise, lice on goats do not come from sheep, cattle or any other livestock animals, but from other goats and are spread from goat to goat through direct body contact (e.g. goats housed close together or running side-by-side in a flock) and through the sharing of louse and nit infested rugs, brushes, combs and shearing equipment. Eggs, nymphs and adult lice which are rubbed off onto yards, posts and trees in a paddock, can also potentially be collected by other

sheep or goats that happen to come by and rub their bodies up against the same spot/s.

Lice tend to infest sheep and goats most commonly during the seasons of Winter and Spring, however, they can be present all year 'round if conditions are favourable.

Lice on sheep do not come from goats, cattle, camels, alpacas or any other livestock animal species, but from other sheep

and are spread from sheep to sheep through direct body contact (e.g. sheep housed close together or sheep running side-by-side in a flock) and through the sharing of louse and nit infested rugs, shearing equipment, brushes and combs. Likewise, lice on goats do not come from sheep, cattle or any other livestock animals, but from other goats and are spread from goat to goat through direct body contact (e.g. goats housed close together or running side-by-side in a flock) and through the sharing of louse and nit infested rugs, brushes, combs and shearing equipment. Eggs, nymphs and adult lice which are rubbed off onto yards, posts and trees in a paddock, can also potentially be collected by other

sheep or goats that happen to come by and rub their bodies up against the same spot/s.

Author's note: Although lice are generally host-specific, one of the sucking lice species of goats (Linognathus africanus) will cross-infect sheep and vice versa.

Lice parasites on goats or sheep can infest any region of the animal's wool or hair, but heavy infestations will

tend to accumulate around the poll, dorsal neck, withers, lateral neck, back-line and tail base of the animals. These are the areas of the coat or fleece that farmers will need to search through most carefully when suspecting of lice on

their livestock animals. Although most sheep and goats affected with lice will have only mild to moderate infestations

of the insects, enough to cause annoyance, restlessness and coat damage (e.g. wool scratching and damage), but nothing more, some animals will go on to develop severe infestations of lice, which can potentially become health-threatening (particularly if the lice are sucking lice).

Those goats or sheep which are prone to heavy infestations of lice tend to be those that are already debilitated or neglected in some way. Goats and sheep that are starved or malnourished, over-crowded, thin, wormy, aged, ill, stressed, over-cold and otherwise neglected are prime candidates

for louse infestation.

Goats are infested with two main Genuses of lice: a biting louse Genus called Damalinia (three species

of Genus Damalinia infest goats: Damalinia caprae, Damalinia crassipes and D. limbata) and

a sucking louse Genus called Linognathus (two species of Genus Linognathus infest goats:

Linognathus africanus and Linognathus stenopsis). Sheep are infested with two main Genuses of lice: a biting louse Genus called Damalinia (one species

of Genus Damalinia infests sheep: Damalinia ovis) and

a sucking louse Genus called Linognathus (three species of Genus Linognathus infest sheep:

Linognathus africanus, Linognathus ovillus and Linognathus pedalis).

Author's note - Damalinia ovis is sometimes also called Bovicola ovis.

Heavy infestations of sucking lice are able to cause severe anaemia in their caprine and ovine hosts

and severely infested and weakened goats and sheep (especially older animals) can potentially

die as a result of their infestation. Note, however, that death from

louse infestation is very uncommon in sheep and goats and is generally contributed to by the kinds of adverse living conditions that caused the lice to proliferate in the first place: starvation or malnutrition, neglect, stress, parasitism, over-crowding, poor housing, extreme weather (heat or cold) and severe age or pre-existing illness. Damalinia is the biting louse Genus seen on goats and sheep. Damalinia do not tend to cause anaemia or severe life-threatening debility

in goats and sheep, however, they do tend to irritate their animal hosts to a significant

degree (a trait shared with the sucking lice varieties, which are also very itchy). Biting or sucking lice infested goats and sheep spend a good deal of their time scratching and biting and rubbing (against trees and fences) at the insects in the coat, which results in damage to the hair coat and skin. This can result in significant wool damage to wool-producing sheep and goats (e.g. Merinos, Angoras), which can result in the farmer being penalised at the market (ruined wool does not sell for a good price). The intense itchiness can also result in reduced time spent grazing, which can result in the animal becoming thin (ill-thrift) and not growing well. This ill-thrift can have a negative

impact on the profits of farmers who are trying to grow sheep and goats for their meat.

Lice Treatment - How to Get Rid of Lice in Goats and Sheep:

Lice infestations in sheep and goats can be treated with powders, pour-ons, rinses, dips or sprays containing

pyrethrins (e.g. deltamethrin), permethrins (e.g. cypermethrin), organophosphates

(e.g. diazinon), rotenone, piperonyl, various insect growth inhibitors (e.g. triflumuron and diflubenzuron,

which destroy lice eggs and/or nymphs, rather than adult lice) and other similar insecticidal ingredients. There are many commercially available sheep and goat products designed for the purpose of getting rid of lice in sheep and goats - visit a veterinarian or your local stockfeed supplier for more advice on which products to use.

Please note that organophosphate chemicals (e.g diazinon), pyrethrins and permethrins have a moderate to high potential for toxicity, both in the treated animals and in the humans performing the treatments. If used, products containing these active ingredients must be applied very carefully, according to the strict instructions specified on the product labels (e.g. dosing to correct weight). Owners are advised to take appropriate safety precautions when using such insecticidal chemicals (i.e. only use the products in a well-ventilated place; wear gloves, protective clothing and eye-protection when using the products; consider wearing breathing apparatus when using the products, especially if they are aerosolised products and so on). Farmers are

also advised to be aware of and to take appropriate environmental precautions

when using such insecticide products, including pyrethrins and permethrins (i.e. make sure there is no risk of any pesticide washing into waterways or groundwater supplies or sensitive

ecosystems and so on). Debilitated animals should not be bathed in organophosphates, pyrethrins and

permethrins and sheep and goats should not be allowed to consume products containing these

substances.

IMPORTANT AUTHOR'S NOTE: Only use these sheep and goat lice treatments according to the instructions on the labels (see a local vet or stock advisor for more lice treatment information before using any of these products). Some of these products

can not be used in pregnant or lactating animals. Some of these products are dangerous to overdose. Some of these products need to be applied to sheep or goats within a certain time of shearing

if they are to be effective. Some of these products can not be used in animals producing meat, milk, lambs/kids or wool for human consumption

and, if they are, strict withholding periods may need to be observed. Some of these products

are harmful to the environment, especially fish and waterways. Some of these products are harmful to people (care needs to be exercised in their use). Some of these active ingredients (e.g. diazinon) may be illegal or banned in certain countries because of toxicity and food-chain-accumulation concerns. Some of these ingredients are not allowed to be used in animals whose products are to be

exported to certain countries (e.g. EU - European Union countries). Some of these

ingredients can damage a farm's organic certification if this is present. If unsure of how to treat livestock lice and what rules apply (i.e. which products to use) - please seek advice

from your local vet or stock advisor.

Products that kill lice in sheep (those available in Australia):

Clout-S (active ingredient: deltamethrin).

Diazinon (active ingredients: diazinon).

Di-Jet (active ingredients: diazinon).

Duracide (active ingredients: alpha-cypermethrin).

Ectomort Plus Lanolin Sheep Dip (active ingredients: propetamphos).

Epic Pour-on Lousicide for Sheep (active ingredients: triflumuron).

Eureka Gold OP Spray-On (active ingredients: diazinon).

Fleececare (active ingredients: diflubenzuron).

Flockmaster (active ingredients: sulfur, rotenone).

4-in-1 Liquid Sheep Dip (active ingredients: piperonyl, rotenone, diazinon).

Jetdip (active ingredients: diazinon).

Jetdip 4-in-1 (active ingredients: piperonyl, rotenone, diazinon).

Kleenklip (active ingredients: cypermethrin, piperonyl).

Magnum IGR Pour-On (active ingredients: diflubenzuron).

Outflank Off-Shears Pour-On Sheep Lice Treatment (active ingredients: cypermethrin).

Outlaw (active ingredients: lambda-cyhalothrin).

Spurt (active ingredients: cypermethrin).

Strike (active ingredients: diflubenzuron).

Topclip Blue Shield (active ingredients: diazinon).

Vanquish Long Wool (active ingredients: alpha-cypermethrin).

Zapp Pour-On Lousicide for Sheep (active ingredients: triflumuron).

Products that kill lice in goats (those available in Australia):

Clout-S (active ingredient: deltamethrin).

Diazinon (active ingredients: diazinon).

Di-Jet (active ingredients: diazinon).

Nucidol 200 EC (active ingredients: diazinon).

Pestene (active ingredients: sulfur, rotenone).

All sheep and goats that have been in contact with the infested animals or their infested yards/paddocks, even if they do not appear to be infested, should be treated. Brushes, shearing equipment, grooming gear, rugs and other fomites that could spread lice from host to host should also be

treated to ensure that these are not allowed to remain as sources of reinfestation. Yards (e.g. fences, trees, stockyards) can harbor lice for weeks to months and should be depopulated of all hosts for a period of time (at least 2 months to be safe) to ensure that freshly-treated sheep and goats are not soon reinfested by their environment (check with your vet to be sure that this treatment and environment-spelling-period is appropriate for your property).

Failure to achieve control of goat or sheep louse problems suggests that:

1) the treatment used was not appropriate - i.e. the wrong product was used, an out-of-date product was used, a badly stored, inactive product was used, the wrong dose was given and so on;

2) the treatment used was not applied correctly - i.e. the product was not applied to the whole coat (leaving some lice populations alive and able to breed), the product was not reapplied according to instructions

to kill the newly-hatched lice, some of the animals in the population did not get their lice treatment and so on and

3) there could be a significant source of louse reinfestation remaining - i.e. maybe there is a louse-infested reservoir animal in contact with the treated animals, maybe there are lice in the environment, the shearing gear, the rugs, the stockyards and so on.

Lice pictures 85: These are goats infested with lice.

Lice pictures 86: This is a photo of a goat biting louse.

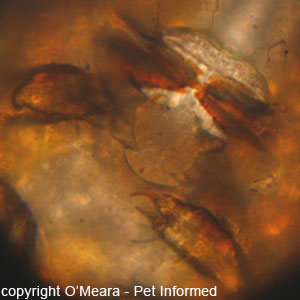

6) Lice eggs (lice nits) - pictures of louse eggs (nits).

Lice eggs or nits are laid on the host animal's hair shafts or feathers by adult female

lice. They are small (0.5-1mm in length), white, elongated structures that look like tiny grains of rice.

They are normally found firmly attached to the shafts of the fur or feathers, somewhere around the base of the hair coat and plumage. Owners can find lice eggs by parting the hair or feathers of the host animal and examining the fur and feather shafts close to the skin.

Under the microscope, lice nits are grey to white in colour. If the eggs have not yet hatched, they are generally rounded on each end. Once hatched, lice eggs usually appear squared-off at one end because their cap-like end has been lost during the hatching process.

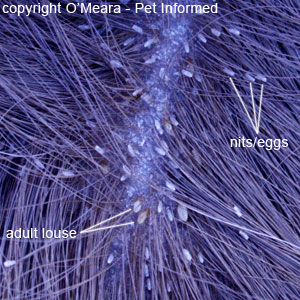

Lice nits picture 87: This lice picture shows an infestation of adult lice and their nits

in the fur of a horse with severe louse infestation. The adult lice and their nits have been labeled.

Lice pictures 88 and 89: These lice pictures show an infestation of lice nits

(lice eggs) in the fur of a mouse with a severe louse infestation. The lice nits have been labeled

in louse picture 89 for ease of identification.

What do lice look like pictures 90 and 91: These lice pictures show hundreds of

lice eggs (nits) in the fur of a horse with lice.

What does lice look like image 92: This is an image of a louse egg or nit that is attached to the hair shaft of

a horse. The egg has a blunt end (i.e. it looks cut-off) indicating that it has hatched already. Non-hatched

eggs are round at each end.

Louse egg picture 93: Not every hatched louse egg is square at the end. When this particular egg hatched, the newly emerging nymph burst out through

the side of the egg, not out through the top. This left a large rent (hole) down the side

of the egg casing.

Lice pictures 94, 95 and 96: These are microscope photos of a louse egg (louse nit) attached to a shaft of mouse hair. This egg is rounded on both ends, indicating that it has not yet hatched out.

7) How can I tell if my pet has lice? - Telltale lice symptoms and signs of lice in cats and dogs and other animals.

The very best way to determine whether or not a pet has lice is to search the fur or feathers

of the animal thoroughly for any signs of lice and/or their eggs. The appearance of lice and

their eggs has been clearly illustrated in the previous sections of this page. Unlike fleas, which are swift-moving

and often tricky to discover during routine fur searches, and unlike mites, which are often microscopic, adult lice are slow moving and clearly visible to the naked eye. They are easy to spot. Lice also leave behind distinctive eggs that are large enough to spot with ease. With a thorough, systematic, top-to-tail fur or plumage search, even small lice burdens should be able to be discovered on an animal host.

Another good way of determining whether or not an animal could have a louse infestation is

to observe the animal's grooming behavior and to examine the animal's skin/fur, droppings and vomit

for signs of louse-related disease or overgrooming. Grooming patterns (e.g. whereabouts on the body the animal

focuses and intensifies its grooming activities); amount of grooming (time spent grooming

in a day); the presence of scratching; furballs in the vomit or droppings; aggression in response to certain

body-regions being handled by owners; the presence of louse-borne parasites and the presence of

lice-associated regions of skin inflammation on the pet's body can all be important clues to louse parasitism.

Aside from the louse infestation signs already discussed in earlier sections of this web-page (e.g. finding

adult lice and nits in the fur), louse parasitism in cats, birds and many other animals (especially rodents) often presents as over-grooming of the hair coat. Animals and birds that over-groom their bodies (spend their entire day grooming their fur or preening their feathers to

almost obsessive levels) may not just be obsessively and fastidiously

clean

like many owners think. Sometimes overgrooming or overpreening can be a sign of skin disease and irritation (itchiness) and louse infestation is a classic example of this.

Alternatively, louse infestations may become so itchy that the animal's intense irritation can not be satisfied with

mere over-grooming and licking activities. Such an animal will often move on to develop outright scratching and biting at the skin in an attempt to alleviate the irritation:

activities that can lead to significant skin trauma and the development of sores and scabs at the sites of louse irritation. Note that in large animals such as horses, pigs, cattle

and other livestock, the animal is often not able to reach the louse infestation with its hooves and teeth and will resort to rubbing up against fences and trees in an attempt to relieve the itching. Large patches of the coat can be scraped off through such rubbing activities (consider the patchiness

of the horse's coat in section 1 of this web-page).

Overgrooming or excessive preening and scratching can lead to secondary signs that owners may also notice. Excessive preening and grooming and chewing of the fur or plumage will often lead to the ingestion of a lot of hair or feathers and this hair or feather consumption can result in the appearance of hair or feathers in the droppings and even the vomiting up or regurgitation of

furballs and matted feathers. High fur ball production can often be a sign of underlying skin disease. Severe overgrooming and scratching of the skin

can also result in hair loss, causing the animal or bird to develop bald patches and regions of thin or damaged plumage and furcoat. Excessive grooming and scratching of the itchy skin

will also cause abrasion and inflammation of the skin. The skin becomes sore and scabby

as a result of this repeated abrasion and animals (especially cats) will often become aggressive or flinch away when their owners pat and touch them on these painful skin areas.

I have had many owners present to the vet clinic complaining of sore backs, bottoms and

tail-bases in their cats, when the problem was skin pain caused by the over-grooming of parasites.

Painful lice infested cats and dogs will be reluctant to be handled; they will growl and hiss (cats) when their owner attempts to touch them; they will curl into an angry, snarling ball when their owner (or a vet) attempts to examine them and they will cry out and even bite or scratch their owners if petted along the back, tail-base or thighs. In very severe cases, over-grooming cats can even bleed from the roof of the mouth. This often-severe hemorrhage occurs when the rough

bristles of the cat's tongue erode the skin of the roof of the mouth over time, rupturing the

large palatine arteries. Surgery may be needed to staunch the bleeding,

but the problem will only be cured by removing the itchy lice parasites.

Another interesting sign associated with the over-grooming of cats in response to skin diseases (including lice) is the exacerbation of allergies in owners who are mildly to moderately

allergic to cats. Some (not all) cat fur allergies in people are not allergies to the fur itself, per se, but allergies to the cat's saliva, which it licks onto the fur during grooming. Such people may be