|

The Female Cat in Heat - The Signs and Symptoms of Feline Estrus.

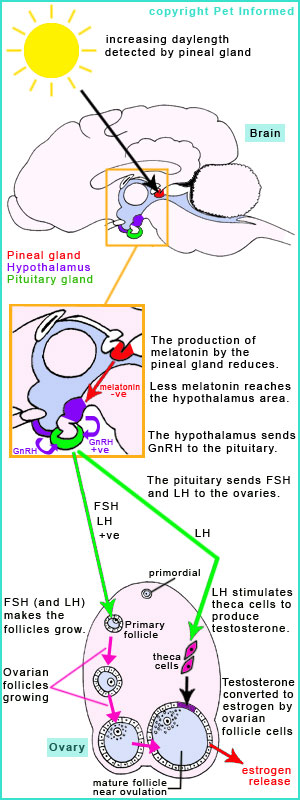

2) What is happening hormonally and physically when a female cat is in heat? A female cat first comes into heat under the influence of increasing daylength (increased "photoperiod"), provided that she has reached the right age for the onset of puberty (as early as 4 months and as late as 18 months, depending on the individual cat, with most female cats hitting puberty at around 6 to 9 months of age) and provided that she has attained at least 80% of her adult bodyweight. When the length of each day (i.e. the hours of daylight per day) is increased, starting in late Winter and continuing during the months of Spring, Summer and Autumn (generally greater than 10 hours of sunlight per day is needed), the change in photoperiod (day-length) is registered by a part of the female cat's brain called the pineal gland (indicated in 'red' on the diagram - right). The pineal gland secretes a hormone called melatonin (it generally secretes this melatonin at night) and this melatonin has an important role to play in the seasonal initiation of the reproductive cycle of the female cat (feline estrus cycle).  When the hours of daylight increase, the pineal gland's production and secretion of melatonin decreases (melatonin is secreted at night, so increased hours of daylight mean reduced hours of night-time and therefore less melatonin). This reduced melatonin has an effect on the female cat's hypothalamus: the region of the brain responsible for the initiation and cyclical management of the feline estrus cycle (the hypothalamus is indicated in 'purple' on the diagram - right). The reduction in melatonin levels triggers the feline hypothalamus to release a reproductive hormone called GnRH (Gonadotrophin Releasing Hormone).

When the hours of daylight increase, the pineal gland's production and secretion of melatonin decreases (melatonin is secreted at night, so increased hours of daylight mean reduced hours of night-time and therefore less melatonin). This reduced melatonin has an effect on the female cat's hypothalamus: the region of the brain responsible for the initiation and cyclical management of the feline estrus cycle (the hypothalamus is indicated in 'purple' on the diagram - right). The reduction in melatonin levels triggers the feline hypothalamus to release a reproductive hormone called GnRH (Gonadotrophin Releasing Hormone).

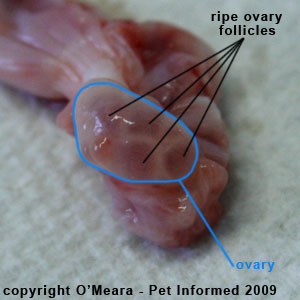

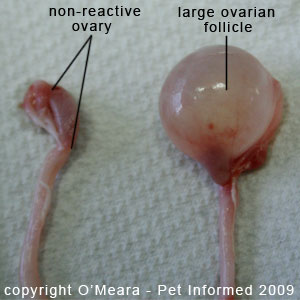

The GnRH released by the female cat's hypothalamus travels via the bloodstream to another region of the cat's brain called the pituitary gland (indicated in 'green' on the diagram - right). It stimulates the pituitary gland cells to release two hormones called, respectively: FSH (Follicle Stimulating Hormone) and LH (Luteinising Hormone). These two hormones travel via the blood to the cat's ovaries and uterus and exert their effects there (diagram - green arrows). The ovaries are tiny organs located on the ends of each of the female cat's two uterine horns. The ovaries contain thousands of gametes (female eggs or ova), which are all waiting to be given the chance to mature and ovulate in the hope that they will be fertilized (by male sperm) and transform into embryos. The pre-pubescent cat ovary: In the quiescent, non-hormone-stimulated, pre-pubescent ovary (e.g. kitten ovary), the ova are all contained individually within tiny, immature, non-growing, non-changing follicles called primordial follicles. Each primordial ovarian follicle is a microscopic, fluid-filled pocket that is lined with a thin layer of cells called granulosa cells. In the pre-pubescent animal, these granulosa cells have a dual role in nourishing the single female gamete (egg, ovum) contained within each follicle and keeping each gamete in an suspended, inactive, dormant state (the female eggs must not be activated prior to the onset of puberty otherwise they will die off and be wasted). The cat ovary at puberty: When the feline reproductive cycle (feline estrus cycle) becomes activated by that combination of appropriately increasing daylength, correct bodyweight and the natural onset of puberty and the FSH and LH levels in the bloodstream begin to fluctuate and rise in response to the increasing GnRH levels, this has an effect on most of the primordial ovarian follicles. The early, initial increases in the levels of FSH and LH in the blood (i.e. at the onset of puberty) have a priming and maturation effect on most of the primordial follicles in the ovary, causing them and the ova contained within them to enlarge slightly. Matured and primed, these slightly larger, now-more-active follicles within the pubescent cat's ovaries are termed primary follicles. Primary follicles do not look a lot different to primordial follicles except that they are slightly larger in size, with a slightly larger ovum (egg or gamete) inside and are lined by a greater number and thickness of granulosa cells. Primary follicles are, however, a lot more reactive and responsive to the effects of ongoing increases in FSH and LH levels than the remaining still-primordial follicles are and it is the primary follicles that will respond most actively to the rising levels of FSH and LH in the blood and, in doing so, grow in size to the point of ovulation (see next paragraphs). The female cat in heat ... In order for any one primary follicle to progress from the "primary follicle state" and grow and mature and advance to the "ovulatory state" (mature follicle state), FSH and LH levels have to rise more and persist at these increased levels for a period of time (i.e. daylight levels need to be appropriately lengthened and melatonin-directed GnRH levels have to be high). And, of course, once full puberty is reached by the cat and once the correct increase in day-length is achieved, this is exactly what does happen - FSH and LH levels continue to grow and to remain elevated in response to increased GnRH. These increased FSH and LH levels have an effect on some of the more mature and advanced of the primary follicles, causing those in question to enlarge further; to replicate their granulosa cell linings and to develop into large (2-4mm diameter), fluid-filled, raised, cystic structures on the surface of the ovaries. Each of these large, fluid-filled structures still contains a single female gamete (egg/ova), but instead of being called primary follicles, they are now termed "mature follicles." These large mature follicles are now ready to rupture and release eggs into the uterus for possible fertilisation. This egg release, when it occurs, is termed ovulation. The replication of the granulosa cells and the subsequent growth and ripening of the mature ovarian follicles is predominantly mediated by the increases in the blood levels of FSH. Although the increased LH levels do have an important, albeit more later-stage, role to play in the final ripening and maturation of the ovarian follicles, the increased LH levels have another more important function that has not yet been mentioned: one which is vital to the female cat actually displaying and showing the signs of "heat" and estrus. LH has an important role to play in the ovary's production of the reproductive hormone: oestrogen (also spelled estrogen). In addition to the granulosa cells lining the ovarian follicles, the ovary has another population of secretory cells called theca cells. Under the influence of LH, these theca cells convert blood cholesterol into androstenedione (an anabolic steroid) and from there into testosterone (yes, female animals do produce testosterone). This testosterone travels from the theca cells into the granulosa cells of the maturing follicles where, under the influence of FSH, it is converted into estrogen (to be precise: estradiol-17B). As the ovarian follicles mature and the granulosa cells divide and multiply and grow in number, so too does the ovarian output of the female reproductive hormone: estrogen. More granulosa cells means more estrogen produced and so, consequently, the growth and maturation of the ovarian follicles is always accompanied by an increase in the levels of blood estrogen. Estrogen is the hormone that makes female cats exhibit the kinds of "cat in heat" behaviors that notify us when a cat is receptive and entering the feline estrus state. It is because of the rising estrogen levels associated with mature ovarian follicle development that female cats in heat exhibit such sexualised behaviors as: calling for males; aroused interest in males of their own species; standing to allow mating; "nymphomania" (excessive sexual interest and mating drive); "rolling around on the floor" (as told to me by many owners) and excessive affection for their owners (in-heat cats often drive their owners nuts by constantly putting their bottoms in their owners' faces and yowling at and rubbing up against them). The point at which these sexual behaviors are at their most obvious (the point where the female cat will stand for the male and allow mating - i.e. true estrus) is at the peak of ovarian follicular growth when ovarian follicles are at their biggest and estrogen levels at their highest. It is a perfect system for maximising the chances of pregnancy - the female cat ends up being most receptive to the male cat (estrogen-mediated) at the exact time that mating is called for (when the follicles are at their most ripe and about to ovulate). Additional notes for completion: Estrogen has the added effect of stimulating the granulosa cells to become even more sensitive to FSH such that, as the follicles mature, the granulosa cells become more and more responsive and rapidly growing as time moves on. Thus, the speed of follicle maturation increases more and more (a positive feedback effect) as estrogen increases. The estrogen and LH have a positive feedback on estrogen production as well. Together, estrogen and LH cause the theca cells to multiply, resulting in an overall increase in testosterone output from these cells and a corresponding increase in estrogen production by the granulosa cells of the ovarian follicles.   Female cat in heat: This is an image of an ovary that came from a cat in heat (picture added 3/11/09). The ovary is dotted with many round, fluid-filled pockets that are about 2-4mm in diameter. These are ripe, estrogen-secreting ovarian follicles that are on the verge of ovulating.    Female cat in heat image 1: This is a picture of a female cat in heat being desexed (spayed). You can see that there is a giant, balloon-like, cyst-like structure on end of one of her uterine horns (the uterine horn that is uppermost in the picture - nearest the scalpel blade). This is a giant, fluid-filled ovarian follicle, which is present on her right ovary. Female cat in heat pictures 2 and 3: This is a close up view of the ovary with the giant ovarian follicle (ovary on right). This is a very extreme, atypical example of a mature ovarian follicle (this follicle may have originated deep within the ovarian tissue and was unable to ovulate properly). Most mature ovarian follicles only get to about 2-4mm in diameter before they burst and release their eggs (ovulate). Being so atypically large, is possible that this may be in fact be an "ovarian cyst" (an abnormal, slow- to non-ovulating, estrogen secreting follicle) rather than a normal ovarian follicle. 3) What does a female cat in heat look like? - Clinical signs and symptoms of heat in cats (includes pictures). The female cat in heat exhibits many behavioral signs to notify male cats and her owners of her receptive state and her desire for breeding. These include:

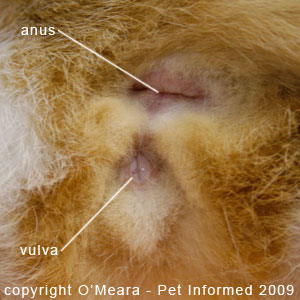

3a) Receptive, crouching body posture - lordosis or "standing estrous". When the female cat in heat is ready to mate, she adopts a crouching posture called "lordosis." She places her elbows on the ground, crouches with her back legs and, bowing her spine into a tight, over-extended "U", elevates her bottom into the air by standing on the toes of her back feet. At the same time as this posture is adopted, the female cat holds her tail to the side, exposing her vulva to encourage mating by the male cat. The in-heat female cat adopts this posture in the presence of an entire male cat (often in response to "scruffing" by the male cat) and will often maintain this posture patiently until the male cat is ready to mount and proceed with mating. Pet owners who suspect that their female cats may be in heat can often induce their animals to "display" lordosis by gently "scruffing them" (grasping the roll of skin at the back of the female cat's neck). Cats in heat will often drop into a lordosis posture in response to this scruffing for it mimics the breeding activities of the male tom cat (male cats usually grasp the scruff of the female to signal their intention of mating).  Female cat in heat picture 4: This is a female cat in heat showing the classic "lordosis" posture. She has her elbows on the ground (table top) and is crouching on the toes of her hind-feet with her bottom raised in the air. Her tail is held to the side such that her genitals are displayed.  Female cat in heat picture 5: This is a female cat in heat showing the classic "lordosis" posture. She has her elbows on the ground (table top) and is crouching on the toes of her hind-feet with her bottom raised in the air. Her spine is so hyper-extended and bowed in this photo that her genitals are actually protruding out past the level of her tail, which is held to the side. This particular photo shows how patient female cats in heat can be. This particular cat was happy to maintain this patient table-top lordosis posture without any need for holding by her owner. This unmoving, "standing still" for the male cat is why we often term it "standing estrous."  Female cat in heat picture 6: This is a female cat in heat showing the classic "lordosis" posture (this photograph is taken from the other side of the cat). She has her elbows on the ground (table top) and is crouching on the tip-toes of her hind-feet with her bottom raised in the air. Her tail is held to the side such that her vulva is displayed. Despite this taut pose, she is relaxed and affectionate, responsive to being rubbed and patted by the humans around her.   Female cat in heat pictures 7 and 8: This is a photo of the same female cat in heat showing the classic "lordosis" posture as it appears from behind (the photograph is taken from the rear end of the cat). The cat has her elbows on the ground (table top) and is crouching on the tip-toes of her hind-feet with her bottom raised in the air. You can see how tightly her tail is held to the side, such that her genitals are displayed to encourage mating by the male cat (tom). 3b) Receptive tail placement - cat's tail held to the side. When the female cat in heat is ready to mate, she adopts a crouching posture called "lordosis" or "standing estrous." She places her elbows on the ground, crouches with her back legs and, bowing her spine into a tight, over-extended "U", elevates her bottom into the air by standing up on the tip-toes of her back feet. At the same time as this posture is adopted, the female cat holds her tail tightly to the side, exposing her vulva, to encourage mating by the male cat.   Female cat in heat pictures 9 and 10: This is a photo of the same female cat in heat showing the classic "lordosis" posture as it appears from behind (the photograph is taken from the rear end of the cat). You can see how tightly her tail is held to the side, such that her genitals are displayed to encourage mating by the male cat.   Female cat in heat pictures 11 and 12: These are some close-up images of the same female cat in heat showing the classic "lordosis" mating posture as it appears from behind (the photo is taken from the back end of the cat). You can see how firmly the estrus cat's tail is held to the side, such that her genitals (vulva) are displayed to encourage mounting and mating by the male cat. 3c) Treading the back legs. When the female cat in heat adopts the crouched, lordosis posture she will often "tread" or "paddle" with her back feet. Treading is when the female cat in lordosis posture lifts each back foot alternately, in rapid succession, such that she appears to be "walking on the spot" (i.e. she is stepping or walking with her back legs, but not actually going anywhere). It is thought that the treading, which causes the female's genitals to jiggle up and down as she "walks," might help to induce more active thrusting by the male cat during copulation, such that ovulation (which is induced in response to mating friction in the feline species) is more likely to occur. It is difficult to illustrate "treading" with still photographs, which is why I have used a series of pictures (below) in an attempt to indicate the action.

Serial sex hormone measurements - measuring the levels of estrogen (estradiol-17B) in the female cat's blood: As described in section 2, when ovarian follicles grow in size and approach the stage of maturation and ovulation (the time when mating is most likely to result in pregnancy), they secrete increasing quantities of a hormone called estrogen (17B-estradiol) - the hormone which is responsible for producing the signs of estrus and mating-receptivity in the female cat. It thus follows that measuring the levels of estradiol-17B present within the female cat's blood can give us some indication of when the growth phase of the ovarian follicles is occurring and when the first signs of feline estrus behaviour are likely to be seen. When a female cat is not actively growing ovarian follicles (e.g. during the Winter, off-season, "anestrus" phases of the feline estrus cycle and/or during the post-ovulation, non-receptive, "interestrus" or "diestrus" phases of the feline estrous cycle), the level of 17B-oestradiol in the blood is usually very low (less than 15pg/ml). "Follicular activity is defined as plasma estrogen concentrations above 20pg/ml" (reference 1). When the female cat is entering the phase of follicular growth (e.g. during the "in-season" stages of proestrus and estrus), the estrogen levels in the blood stream will rise rapidly - generally reaching levels that are just in excess of 20pg/ml within the very first day of follicular growth beginning. Over the next few days, as the ovarian follicles continue to grow under the influence of FSH and LH, these estrogen levels will continue to rise, reaching upper levels of around 50pg/ml (and even as high as 80pg/ml) as ovarian follicular growth reaches its peak. This estrogen peak is presumably the time when the cat is at her most "in-heat" and receptive to mating and successful ovulation is most likely to be achieved. By measuring a female cat's estrogen levels in series (taking a series of measurements over time), the cat owner can often detect when the follicular growth phase of the feline estrus cycle is occurring because the estrogen levels will rise rapidly within a period of days and exceed 20pg/ml. Important author's note: Do not wait for the cat to reach a certain pre-selected estradiol level before you say that she is in heat and receptive to mating. Let her behaviour guide you. Some cats (about 10% of cats) will start to display the signs of heat on the very first day of ovarian follicular growth when estradiol levels are only around the 20-25pg/ml mark (these cats may mate, however, this early-stage mating may not necessarily lead to successful ovulation because the follicles are not yet fully mature). Many other cats will hold back and will need to have blood oestrogen levels up around the 35-40pg/ml mark and more before they are in behaviorally in-season, receptive to mating and ready to ovulate. Basically: all cats are individual and so you will need to use a combination of clues (estrogen levels, behaviour and so on) in order to tell when any one cat is in heat and receptive to mating. As a good reproduction lecturer once said to me: "There are no biological absolutes." Important author's note: The duration of the follicular growth phase is variable from cat to cat and ranges from 3-16 days (average 7 days). Ovarian follicles, once initiated to grow by FSH and LH surges from the pituitary, will grow to size quickly and a cat can go from not-in-heat to fully in season and receptive to mating within a mere 12-48 hours. An individual cat, should it happen to be a "short-season" cat with only a short follicular growth phase, might then go on to ovulate or otherwise lose its ripe follicles (via natural follicle death or atresia) within a period of only a few days (i.e. the total follicular growth and ovulation phase could be as short as 3 days with the cat only showing estrus signs for a couple of days). A cat breeder, waiting for estrogen results to come back from the lab, might miss such a short period of follicular growth and fertility (which will often be accompanied by only a short duration of estrus signs - estrus signs being dependent on the estrogen made by the follicular growth phase) if he or she isn't also monitoring the cat's sexual behaviour and receptivity very closely. This could result in that breeder failing to get that queen pregnant. In summary: unless you are prepared to measure estrogen levels every 2 days (which is not nice for the cat, seldom practicable and very costly), you should never 100% rely on estrogen measurements alone to tell you when a cat is in the follicular stage and ready for mating (you still need to monitor the cat's behaviour). An extra point for completeness: To throw an additional spanner in the works, some female cats will even display feline estrus behaviours for up to 4 days after the follicular phase has ended (i.e. ended due to successful ovulation or due to the natural regression of the over-ripe ovarian follicles with age). This is because the estrogen levels in the blood can take a few days (about 4 days) to recede once the follicular phase has ended. These cats may even show mating behaviour during this post-follicular phase, but they are unlikely to ovulate or fall pregnant because no follicles exist. It is for this reason that, even though the duration of the follicular growth phase is only 3-16 days (average 7 days), the duration of feline estrus signs can last up to 21 days in a small number of individuals. The follicles have gone, but the estrogen effect on behaviour still lingers. Such a phenomenon can make the timing of cat breeding tricky. A cat breeder might leave it too late to mate a female cat if the cat has short-lived ovarian follicles or happens to be an early ovulator (short follicle growth period), but has an overly-long estrogen drop-off time after follicle-loss (i.e. the cat will appear in-heat and receptive and will mate, but will have already lost the much-needed mature follicles that are so essential for successful pregnancy). It is because of these kinds of individual variations in breeding cat reproductive cycling that you will need to use a combination of clues (serial estrogen levels, behavioral changes and so on) in order to tell when any one cat is in heat and receptive to mating. Vaginal cytology examinations: As the female cat's body comes under the influence of increasing estrogen levels, specific changes occur in the consistency of the mucus (mucus "clearing") and of the cells lining the cat's vagina. The cells and mucus can be sampled from the vagina using a moistened, sterile cotton swab (cotton tip); smeared onto a slide; stained and examined under the microscope in order to determine whether the cat is approaching season or not. The technique is commonly employed in the bitch (female dog) to determine if season is approaching. It is less commonly used in the female cat for several reasons:

Male cat attraction: Male cats can detect a female cat approaching heat much better than we humans can. When a female cat comes into heat, she releases pheromones and hormones in her urine that notify male cats of her increasing receptivity and her impending estrus. At the peak of her oestrous cycle she will also call and wail, notifying males of her desire to mate, and this also attracts them to her. For these reasons, the attraction of male cats into the yard and garden can be a very useful indicator to cat owners that their female cat is approaching, or has already reached, the receptive stages of estrus. Lots of male cats in the yard means that it is time to lock up the ladies! Author's note: The presence and smell of male cats in the vicinity will also cause the queen to display the signs and symptoms of heat (e.g. calling, rolling, affection and so on) much more vigorously and obviously than she might if no cats were around and her only company was her human owner/s. This also helps to make the signs of feline estrus more recognizable and evident to the female cat's owners. 5a) Can a spayed cat come into heat or show feline estrus signs? The answer should be no - no ovaries means no estrogen production and, therefore, no "female cat in heat" signs. Occasionally, however, a cat who has been spayed will come back into heat weeks to months (even up to 5 years later) after she has been desexed. This is, naturally, very perplexing and annoying for the owner (part of the reason why many people get their female cats desexed is to prevent them from displaying some of the more annoying signs of cat heat like hypersexuality, calling, roaming and tom cat attraction) and often cat owners will question whether or not the surgery has been performed correctly at all. Well, the good news is that, despite the in-heat symptoms, the cat probably has been desexed successfully and so can not fall pregnant (unless some major record-keeping mistake has been made and the cat that was thought to have been spayed was not ...). The bad news is that the cat has probably had some of its ovarian tissue (a portion of ovary or ovarian-type tissue) left behind, such that the ovarian follicles present on this ovarian tissue (called ovarian remnants) are now cycling and producing estrogen. It is this cycling and estrogen production by the ovarian remnant tissue that accounts for the cat showing the signs of being in heat. This is not a huge problem as far as the cat is concerned (she won't get pregnant), however, the signs of cat heat and the attraction of male cats into the yard will continue so long as the ovarian remnants remain and this can be tiresome for the cat-owner. Cats with ovarian remnants should not be able to get pregnant because the ovarian tissue left behind is not in communication with a uterus. What the ovarian remnant cat can occasionally develop, however, is a condition called a stump pyometron: a bacterial infection of the small section of uterine body (uterine stump) that has been left behind after the spay surgery. Pyometron is an infection of the uterus or uterine stump that most commonly develops under the hormonal influence of a cycling ovary or ovarian remnant (i.e. it results from the cycle of estrogen and progesterone release by the ovary). The infection that occurs can be life threatening. Animals without cycling ovarian tissue at all are very unlikely to suffer from the pyometra condition and so, for this reason, it is advisable that cats with symptoms suggestive of ovarian remnants (return to heat, calling etc) undergo work-up and surgery to remove the section/s of ovary left behind. This should prevent a 'stump pyo' from occurring. Author's note: The presence of ovarian remnant syndrome (the term given to the collection of signs and symptoms that are associated with the presence of ovarian remnant tissues) does not always mean that the vet has performed the spaying surgery incorrectly. Some cats are actually born with pockets of ovarian tissue that are located outside of the ovary body - typically further down the ovarian pedicle, but occasionally (very rarely) even elsewhere in the body (these are termed ectopic ovaries)! What happens in these cases is that the precursor stem cells that create the ovarian follicles in the embryo sometimes get lost during their migration to the ovary site and set up shop elsewhere in the body. In these cases, there is no way that the vet can possibly know that a portion of ovarian tissue has been left behind, until the cat returns to heat after surgery. Differential (alternative) diagnosis of ovarian remnant syndrome: Occasionally estrogen-secreting tumors of both ovarian and non-ovarian cellular origin can develop, which secrete enough estrogen to elicit signs of heat in entire or desexed female cats. This is not true ovarian remnant syndrome nor a consequence of poor desexing technique, but it can appear very similar (i.e. the cat returns to heat even after desexing). These secretory cancers can arise in an ovarian remnant that has been left behind by poor-spaying or they can occur in other non-ovarian tissues anywhere in the body. Alternatively, if a cat already has an estrogen-secreting ovarian cancer and is subsequently spayed to remove it, the cat may continue to shows signs of heat after the desexing surgery if that secretory tumour has managed to spread cancer seeds (metastasise) into other organs prior to the desexing surgery occurring. The tumour 'seeds' can be equally secretory, producing signs in the now-desexed cat that are similar to those of ovarian remnant syndrome. Very rarely, some spayed cats can even exhibit a centrally-mediated (brain mediated) persistence of estrus signs and nymphomania. This is thought to be an adrenal gland mediated condition: an effect of the adrenal cortex converting body testosterones into estrogens. Diagnosis of ovarian remnant syndrome: There are several ways of diagnosing this condition and ruling out the differential diagnoses of estrogen-secreting neoplasia (cancer) and centrally-mediated nymphomania. 1) The nature of the heat symptoms: In all three of these conditions, the cat in question should show signs of coming into heat sometime after spaying. In the case of ovarian remnant syndrome, however, this heat activity should be observed to 'come and go' as the remaining ovarian follicles cycle through repeated stages of growth (the follicles grow - producing estrogen and signs of feline estrus) and disintegration (the follicles ovulate or die off, turning into corpus lutea that make progesterone instead of estrogen, without the associated signs of heat): a cycle typical of the reproductive cycle of the normal, entire female cat. In the case of estrogen-secreting tumors and centrally-mediated nymphomania, however, the symptoms of heat are generally more persistent and non-waning because the production of estrogen by these diseases is generally more persistent and non-waning.  2) Detection of ovulation and the response to certain pituitary hormones: Because ovarian remnants are essentially normal ovarian tissue (just tissue that has been left behind), they should produce ovarian follicles that grow and ovulate normally (as described in point 1, above) and that respond to certain regulatory pituitary-derived hormones (e.g. GnRH, hCG, LH) in the normal ovarian way. Estrogen-secreting tumors, on the other hand, do not produce normal ovarian follicles that ovulate and nor do they respond to pituitary-derived hormones in the normal way. Consequently, proving that a cat's estrogen-secreting tissue is capable of ovulation and that it responds to pituitary hormones in the normal fashion is another very good way of confirming the presence of ovarian remnants (as opposed to estrogen-secreting tumours and centrally-mediated nymphomania). This can be done in two ways: 2) Detection of ovulation and the response to certain pituitary hormones: Because ovarian remnants are essentially normal ovarian tissue (just tissue that has been left behind), they should produce ovarian follicles that grow and ovulate normally (as described in point 1, above) and that respond to certain regulatory pituitary-derived hormones (e.g. GnRH, hCG, LH) in the normal ovarian way. Estrogen-secreting tumors, on the other hand, do not produce normal ovarian follicles that ovulate and nor do they respond to pituitary-derived hormones in the normal way. Consequently, proving that a cat's estrogen-secreting tissue is capable of ovulation and that it responds to pituitary hormones in the normal fashion is another very good way of confirming the presence of ovarian remnants (as opposed to estrogen-secreting tumours and centrally-mediated nymphomania). This can be done in two ways:2a. Measure the cat's progesterone levels one week after the signs of estrus (heat) have resolved. In a cat with ovarian remnant syndrome, the cessation of estrus signs should be the result of ovulation or atresia (death) of the estrogen-secreting follicles and their replacement with progesterone-secreting corpus lutea (in the case of ovulation). A progesterone level of >2ng/ml is suggestive of ovulation having occurred (i.e. a diagnosis of ovarian remnant syndrome). Note, however, that not all cats spontaneously ovulate with each estrus period (unlike dogs who spontaneously ovulate, cats are usually "induced" to ovulate through the friction of their mating activities) and the waning of feline estrus signs may be the result of the ripe follicles aging and regressing (follicle atresia) rather than ovulating. In these situations, no corpus lutea will be formed and the progesterone levels will stay low. This does not mean that the cat is actually negative for ovarian remnants, it just means that spontaneous ovulation did not occur during that estrus cycle (using hCG is more guarantee of an ovulation response in the cat - see section 2b). 2b. Induce the cat to ovulate using hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin) or GnRH (gonadotrophin releasing hormone). If a cat with ovarian remnant syndrome is given either 250IU/cat of hCG or 25ug/cat of GnRH whilst she is in heat (showing signs of heat), then she should ovulate [1,8]. A week later, her serum progesterone levels should be >2ng/ml, which is supportive of ovulation having occurred. A spayed cat with an estrogen secreting tumour or a centrally-mediated nymphomania should not ovulate in response to hCG or GnRH and, consequently, no rise in progesterone levels one week after administration of these hormones should be found. 3) Surgical exploration: The definitive way to find an ovarian remnant is to take the cat back to surgery and have a look inside the cat's abdomen for the remnant. Not that they are always that simple to find: ovarian remnants can be very small and hard to find (they are just a small cluster of cells after all). The BEST time to perform an exploratory surgery on an ovarian remnant cat is when it is actively showing the signs of being in-heat. At these times, the ovarian follicles should be large and easy for the vet to spot. 4) Corticosteroid administration: If centrally-mediated (adrenal-origin) estrogen production and nymphomania is suspected, it can be diagnosed to some extent through the administration of therapeutic treatments (i.e. a treatment trial). Administration of short-acting corticosteroids should result in the disappearance of the in-heat symptoms if this adrenal condition is present. Treatment of ovarian remnant syndrome: The surgery to remove an ovarian remnant is almost identical to the surgery performed when a spay procedure is done, except that, in this case, there is no uterus to remove. The surgeon enters the animal's abdomen and investigates the regions just behind each of the cat's kidneys until the ovarian follicles are found and removed. If they can be found and removed, then all of the symptoms of heat and cycling should resolve for that cat. The BEST time to perform corrective surgery on an ovarian remnant cat is when it is actively showing signs of being in-heat. At these times, the ovarian follicles should be large and easy for the vet to find.

5b) Can a pregnant or lactating cat come into heat or show feline estrus signs? The answer is yes. At the very end of pregnancy, just prior to the onset of parturition (birthing), the level of progesterone in the female cat's blood drops off (progesterone is the hormone responsible for maintaining the non-cycling, pregnant state) and a spike in the level of blood estrogen occurs. This spike in blood estrogen levels can be enough to cause the late pregnant cat to display the signs and symptoms of being in heat and to even allow mating to occur! The mating is unlikely to result in pregnancy in the already pregnant cat. If this estrogen spike occurs very late in the pregnancy, the estrogen levels may still be elevated even after the cat has given birth. This could result in a lactating cat showing signs of being in-heat early in her lactation. She might even permit mating to occur, though this would be rare behaviour in a female cat with newborn kittens (they are usually protective of them) and would be unlikely to result in pregnancy (the uterine environment immediately following a birth is not generally conducive to the successful conception and implantation of a whole new litter). Normal return to estrous cycling tends to only occur once the kittens have been weaned (i.e. a lactating cat has to have her kittens removed before she can resume her normal hormonal reproductive cycling). If the suckling kittens are removed from the female cat early (even within the first week of their birth), then normal estrus cycling will usually begin in about 4 weeks (range 2-8 weeks). Estrus cycling can resume within as little as a week post-weaning in certain individuals. 5c) Do all female cats show recognisable signs of heat? - Can some cats be in season and able to fall pregnant without showing signs? Not all female cats show recognisable signs of being in heat every time that they are in estrus. Some queens (particularly shy or subordinate queens) make identifying heat symptoms difficult for their owners by deliberately not displaying them in the presence of their owners. This is particularly the case in queens who have previously been punished by their owners for displaying such "annoying" on-heat behaviors as rubbing and calling (the punishment doesn't stop the behaviour by the way, it just makes the cat more secretive about it in the owner's presence). Such cats may only display their "in heat" signals when they are let outside or they are otherwise placed into the environment and presence of entire male cats. Some female cats will only display their heat behaviours in the presence of a male cat (i.e. they do not display for "non-cats", including their owners). Owners of such cats might never see their female cat show the signs of estrus if she is never allowed to come into the vicinity of a male cat. The feline pecking order in a household can also have an impact on whether a female cat shows the signs of estrous or not. A timid queen in a household with other, more dominant, entire queens may not display obvious heat behaviours in their presence, even though her female reproductive cycle is completely normal. At other times, the problem of estrus detection is not that of the cat, but of the non-observant or non-familiar owner. Some owners simply can not tell if their cat is in heat even though the cat is clearly showing the normal signs of feline estrus. This is particularly the case if the female cat in question is naturally affectionate (the owner can not tell whether she is in heat or just being her normal affectionate self). 5d) Can some cats show continuous estrus behaviour during the entire breeding season? The answer is yes. There are certain female cats who appear to never "go off season" during the months of the breeding season. That is, they continue to show signs of being in heat right through the breeding season without the normal, cyclical, "receptive to non-receptive" interchange that is typically seen in most cycling cats. These constant-heat cats are not necessarily abnormal. Follicular growth is not always an all or nothing process - i.e. it is not always the case that all-follicles-grow and then all-follicles-regress. Follicular growth can sometimes occur in waves such that, at the same time as a group of large follicles reaches maturity, another group of follicles might also exist that are intermediate in size. When the first group of mature, estrogen-secreting follicles regresses, the next lot of growing follicles might be following so closely behind them that no appreciable drop in estrogen level is noticed. Such a cat would remain symptomatically in-heat with no pause in feline estrus activity and heat symptoms. Note - this is not common and does not happen in most cats (usually there is a bit of a gap between successive waves of follicles such that estrus behaviours wane in between), but it can be a reason why some cats appear to constantly be in season during their entire breeding season. 5e) Can some cats cycle and show estrus signs all year-round? The answer is yes. As discussed in section 2, the onset of estrus cycling in the cat is initiated by increasing daylight length (increased photoperiod) during the seasons of Spring, Summer and Autumn. Cats who are exposed to strong artificial lighting for periods of more than 10 hours a day for days at a time (e.g. cats who live in apartments and office blocks) can potentially cycle all year 'round. 5f) How long does the receptive, estrus phase last in cats? The breeding season of the cat lasts from late Winter, through Spring, Summer and Autumn. During this breeding season, the cat cycles many times through the entire oestrus cycle, spending a period of each oestrus cycle in the "receptive phase" that is termed estrus or heat. Each receptive estrus phase lasts from 1-21 days (depending on the individual cat) with the average feline "heat" or estrus phase lasting about 7 days. To go from this female cat in heat page to the Pet Informed home page, click here. 1) Feline Reproduction. In Feldman EC and Nelson RW: Canine and Feline Endocrinology and Reproduction, 2nd ed. Sydney, 1996, WB Saunders Company.

Common misspellings and spelling variants: oestrous, oestrus,

estrus, estrous, oestris, estris, diestrus, dioestrus, diestrous, dioestrous, diestris, dioestrous, interestrus, interoestrus, interestrous, interoestrous, interestris, interoestrous,

anestrus, anoestrus, anestrous, anoestrous, anestris, anoestrous. |

The feline estrus cycle, otherwise known as the "female reproductive cycle" or "heat cycle" of the female cat, is a repetitive cycle of seasonally and hormonally driven fluctuations in a female cat's fertility and sexual receptivity. Under the estrus cycle's fluctuating hormonal influences, the entire female cat cycles back and forth between being "in estrus" and receptive to mating (i.e. likely be fertile and to fall pregnant) to "not-in-heat" and non-receptive to mating (i.e. unlikely to fall pregnant) during the feline breeding season (Spring to Autumn). The various periods of sexual receptivity (termed "estrus") and sexual non-receptivity are characterised by very distinct behavioural characteristics, sex hormone fluctuations and reproductive tract structural changes, all of which are essential to making the female cat either accepting of mating and pregnancy (in the case of the female cat in heat) or non-receptive to these, as her physical and hormonal situation demands.

The feline estrus cycle, otherwise known as the "female reproductive cycle" or "heat cycle" of the female cat, is a repetitive cycle of seasonally and hormonally driven fluctuations in a female cat's fertility and sexual receptivity. Under the estrus cycle's fluctuating hormonal influences, the entire female cat cycles back and forth between being "in estrus" and receptive to mating (i.e. likely be fertile and to fall pregnant) to "not-in-heat" and non-receptive to mating (i.e. unlikely to fall pregnant) during the feline breeding season (Spring to Autumn). The various periods of sexual receptivity (termed "estrus") and sexual non-receptivity are characterised by very distinct behavioural characteristics, sex hormone fluctuations and reproductive tract structural changes, all of which are essential to making the female cat either accepting of mating and pregnancy (in the case of the female cat in heat) or non-receptive to these, as her physical and hormonal situation demands.