Fecal Float (Fecal Flotation) Parasite Pictures Gallery.

This fecal float parasite pictures page is a pictorial guide to small-animal parasites

(eggs, oocysts and worm larvae) and non-parasite objects and artifacts that might be seen under the microscope when performing a faecal flotation procedure. This page contains over 100 full-color, photographic images of common small-animal parasite eggs, ova and worm larvae,

which have been viewed through the microscope during fecal flotation testing. This page has been designed as a visual guide to accompany our fecal flotation techniques page. We hope that this page will be a useful guide to help veterinarians, vet nurses, wildlife carers, diagnose-it-yourself pet owners and

other animal keepers to know what they are looking for when they are performing diagnostic fecal

float tests on animal stool and dropping samples.

This fecal float parasite pictures page is a pictorial guide to small-animal parasites

(eggs, oocysts and worm larvae) and non-parasite objects and artifacts that might be seen under the microscope when performing a faecal flotation procedure. This page contains over 100 full-color, photographic images of common small-animal parasite eggs, ova and worm larvae,

which have been viewed through the microscope during fecal flotation testing. This page has been designed as a visual guide to accompany our fecal flotation techniques page. We hope that this page will be a useful guide to help veterinarians, vet nurses, wildlife carers, diagnose-it-yourself pet owners and

other animal keepers to know what they are looking for when they are performing diagnostic fecal

float tests on animal stool and dropping samples.

Aside from the great fecal flotation parasite photos presented on this page, I have also included

pictures of adult parasites and post-mortem photos of severely-parasitised animals to help you to better

understand and appreciate the significance of parasitic diseases in animals.

Every parasite on this page has been richly presented as a complete case study to give you a complete overview of the signs and symptoms and circumstances surrounding the

animal that underwent the fecal float test. After all, parasitism in animals always needs

to be interpreted cautiously, with complete consideration given to an animal's background history,

living circumstances and the presence (or absence) of clinical signs. Where applicable,

I have made mention of important parasite lessons and fecal float interpretation tips that were gained from having performed each of the fecal flotation tests.

These recommendations and

lessons are indicated by the following:

Fecal Float Hints and Tips.

WARNING - IN THE INTERESTS OF PROVIDING YOU WITH COMPLETE AND DETAILED INFORMATION, THIS SITE DOES CONTAIN POST MORTEM IMAGES THAT MAY DISTURB SENSITIVE READERS.

WARNING - IN THE INTERESTS OF PROVIDING YOU WITH COMPLETE AND DETAILED INFORMATION, THIS SITE DOES CONTAIN POST MORTEM IMAGES THAT MAY DISTURB SENSITIVE READERS.

Fecal Float Parasite Pictures Contents:

1) Roundworms in dogs and cats - fecal flotation pictures of roundworm eggs under the microscope:

1a) Roundworms in cats (Toxocara cati) - pictures of feline roundworm eggs and adult roundworms.

1b) Roundworms in dogs (Toxocara canis) - fecal flotation pictures of canine roundworm eggs (ova) and adult round worms.

Both sections include images of adult roundworms in dogs and cats (Toxocara species).

2) Canine whipworm eggs (dog whipworm ova) taken under the microscope.

Includes images of adult whipworms (Trichuris vulpis).

3) Capillaria eggs (an important non-pathogenic parasitic differential diagnosis for whipworms).

4) Coccidiosis and coccidia oocyst parasite pictures:

4a) Coccidia in puppies and dogs (canine coccidia protozoan parasites).

4b) Coccidia in kittens and cats (feline coccidiosis).

4c) Rabbit coccidia - Eimeria.

5) Tapeworm pictures (photos of animal tapeworm eggs and segments):

5a) "Zipper-worm" tapeworms in cats - Spirometra tapeworm eggs and segments.

5b) Feline tapeworm (cat tapeworm) segments - Taenia.

Tapeworms in dogs (canine tapeworm) and other animals - Coming Soon.

6) Hookworm eggs (Ancylostoma eggs) taken under the microscope.

7) Hatched worm larvae (L1 larvae or first stage larva) - live worms seen on fecal float:

7a) Feline lungworm larvae (cat lung worm) - Aelurostrongylus abstrusus.

8) Pictures of multiple parasite infestations seen on the one float.

9) Other non-parasitic objects and artifacts that may be seen on a stool float:

9a) Fecal matter and poop debris.

9b) Pollen.

9c) Plant matter.

9d) Bubbles.

9e) Yeasts and fungi - coming soon.

9f) Bacteria.

9g) Fecal flotation medium crystals.

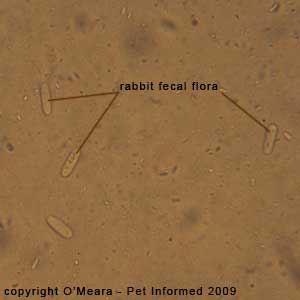

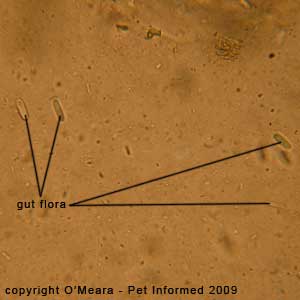

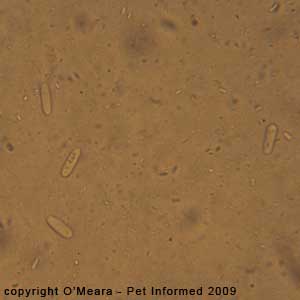

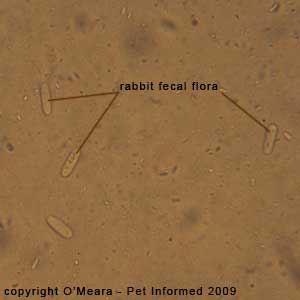

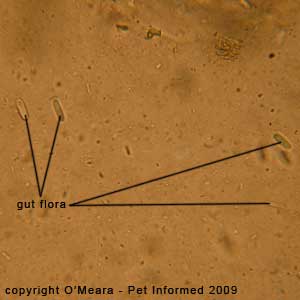

9h) Normal fecal flora - rabbits.

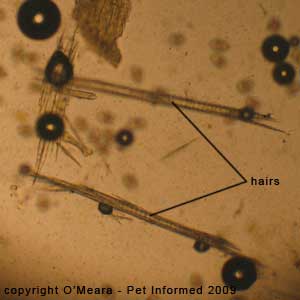

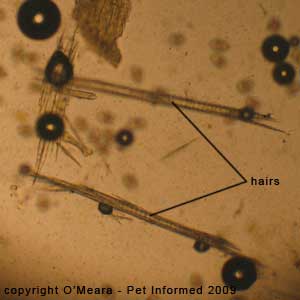

9i) Ingested hairs.

1a) Roundworms in cats (Toxocara cati) - pictures of feline roundworm eggs and adult roundworms.

This section contains photographic images of feline roundworm eggs, which were discovered on a fecal flotation exam of a cat's stools (droppings).

The fecal flotation test was performed on the cat (a stray kitten) because it was emaciated, had severe diarrhea, had no history of prior worming and because it was very depressed and unwell. The fecal floatation test found that the kitten had both roundworm eggs and lungworm larvae (see section 6 for fecal float pictures of feline lungworm)

present in its stools. The kitten was too sick to survive and a subsequent post-mortem examination found that both adult feline roundworms and severe lungworm infestations were present. As the lungworm infestation was very severe and, as only a couple of roundworms were present, the likely cause of the kitten's illness was thought to be the lung worm infestation and not the roundworms (i.e. the round worms were incidental).

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: This case is important because it shows us that merely finding evidence of a parasite (e.g. parasite eggs) on a fecal float is no guarantee that it is responsible

for any or all of the clinical signs of illness seen in the animal. A couple of parasites

(e.g. one or two cat roundworms) may shed eggs into the stools, but not actually be causing any

clinical illness. In this particular case, the fecal flotation test was fortunately diagnostic, however, because the parasite that was actually causing the disease (the feline lungworm) also came up positive on the fecal float.

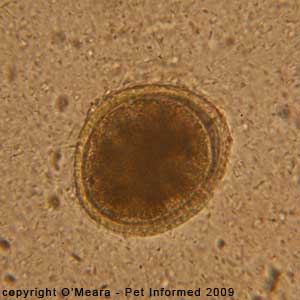

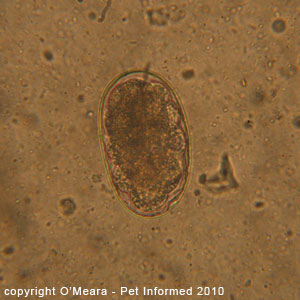

Feline roundworms parasite pictures 1: This is a microscope image of the fecal flotation test that

was performed on the sick kitten with the diarrhea. Four cat roundworm eggs (Toxocara cati species)

are visible in the picture. They are the dark brown, circular structures on the left of the image. A

shrivelled up lungworm larva (linear, elongated, clear-colored object in the upper right corner) is also

visible in this parasite image.

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 10x (100x in total when the 10x

magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account).

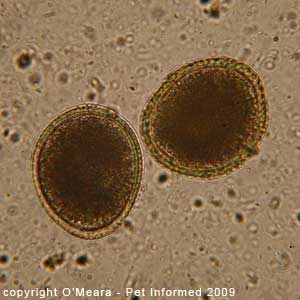

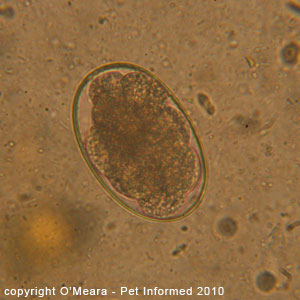

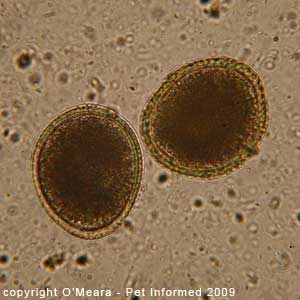

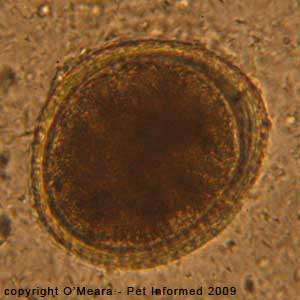

Feline roundworms parasite picture 2: This is a microscope photo of the faecal flotation test that

was performed on the sick kitten with the diarrhea. It is a close-up photo of two of the cat roundworm eggs (Toxocara cati species) that were seen on the float. These roundworm eggs are large, imperfectly round and non-embryonated (non-embryonated means that the worm eggs have not yet developed viable, infective

larval worms within the center of them), with dark brown centers and a thick, lighter-coloured (orange or yellow coloured) wall, which is not smooth, but pitted and dimpled in appearance.

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 40x (400x in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account).

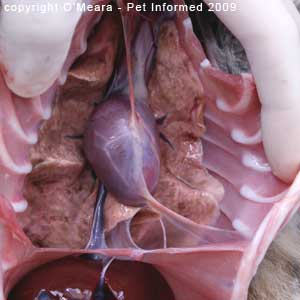

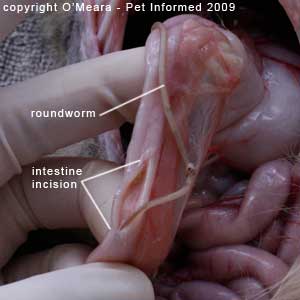

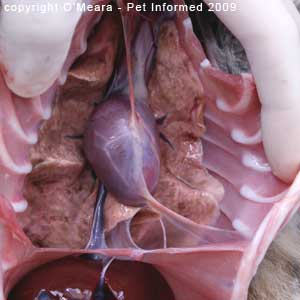

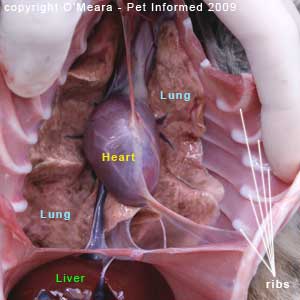

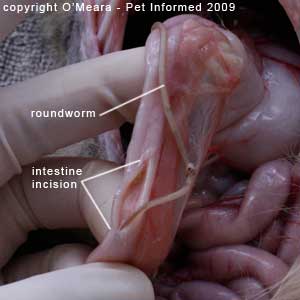

Roundworms in cats parasite picture 3: This is a post-mortem image of the kitten

that had the fecal flotation test performed. An adult roundworm could be palpated within the cat's duodenum (the first part of the small intestine). When the duodenum was held up to the light, the outline shape of the adult feline roundworm could be seen through the

wall of the small intestine.

Roundworms in cats photo 4: This is a post-mortem image of the kitten

that had the fecal float performed. An adult roundworm could be felt within the cat's duodenum (the first part of the small intestine). When the cat's

duodenum was incised (cut) into, the adult round worm was discovered sitting within

the intestinal lumen (the lumen is the central canal of the intestine, where the digested food flows). The roundworm was quite large (about 6-8cm long).

Roundworms in cats parasite picture 5: This is an image of the feline roundworm, once it was outside of the cat's body. The feline roundworm was quite large (about 6-8cm long).

1b) Roundworms in dogs (Toxocara canis species) - fecal float pictures of canine roundworm eggs (ova) and adult round worms.

This section contains photographic images of canine roundworm eggs, which were discovered on a fecal flotation exam of a dog's stools (droppings).

The fecal float test was performed on the dog (a bitch with newborn puppies) because she had diarrhea, had no history of prior worming and because she had just given birth to ten pups a few

weeks earlier. Aside from the sloppy droppings, the bitch and her puppies were otherwise happy and well. Because adult roundworm and hookworm infestations are common in whelping bitches, a

fecal float examination was considered prudent.

The fecal floatation test found that the bitch had high numbers of roundworm eggs present in her stools. The female dog was wormed and massive numbers (>100 worms) of adult canine roundworms were voided in her faeces. As the roundworm infestation was very severe, the likely cause of the bitch's diarrhea was thought to be the round worm infestation. The deworming medication

was curative and the dog's diarrhoea resolved.

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: This case is important because it illustrates just how finding evidence of a parasite (e.g. parasite eggs) on a fecal float exam can often (but not always) lead to a diagnosis, a treatment and a cure for a parasitic disease. In this case, finding the canine roundworm

eggs on the fecal flotation test resulted in the bitch being wormed, which resulted in the worms being

voided from the dog's body (i.e. a cure).

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: Interestingly, despite the numbers of adult roundworms present being very high, there were not all that many roundworm eggs found on the fecal float test. This shows that the

number of eggs or larvae seen on a fecal float test is not necessarily directly proportionate to the number of adult parasites that are present in the animal being tested. A very small population of adult parasites

can sometimes shed a lot of eggs and a very large population of adult parasites can sometimes shed surprisingly few eggs.

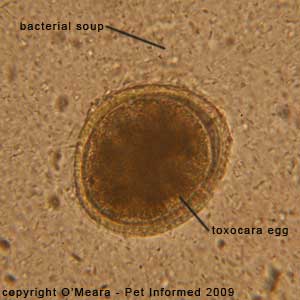

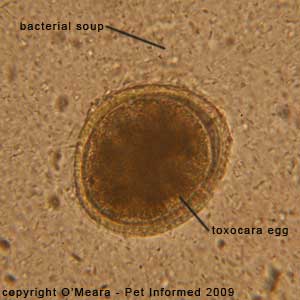

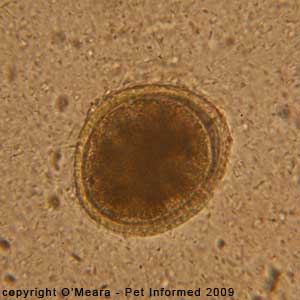

Canine roundworms parasite pictures 6: This is a microscope image of the fecal flotation test that

was performed on the lactating bitch with the diarrhea. One dog roundworm egg (Toxocara canis species)

is visible in this picture. It is the dark brown, circular structure in the centre of the image.

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 10x (100x in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account).

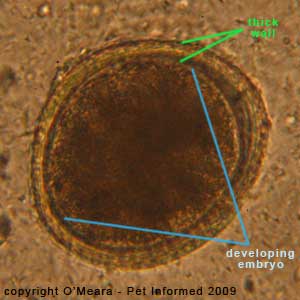

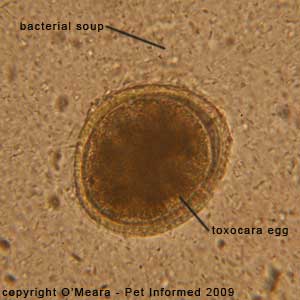

Dog roundworms parasite picture 7: This is a microscope photo of the faecal float test that

was performed on the suckling bitch with the diarrhea. It is a close-up photo of one of the dog roundworm eggs (Toxocara canis species) that was seen on the fecal float. These eggs are large, imperfectly round and non-embryonated (non-embryonated means that the worm eggs have not yet developed viable, infective larval worms within the centre of them), with dark brown centres and a thick, lighter-coloured (orange or yellow coloured) wall, which is not smooth, but pitted and dimpled in appearance.

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 40x (400x in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account).

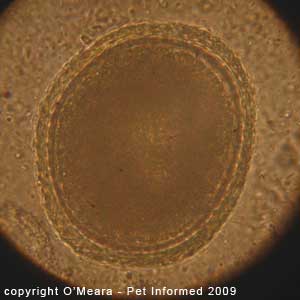

Roundworms in dogs pictures 8 and 9: These are microscope images of a canine roundworm egg.

The egg floats within a background of millions of tiny fecal bacteria (bacterial soup).

Author's note: You will always find millions of bacteria on a fecal float examination. They are natural residents of the colon and faeces and are of little diagnostic significance on a fecal flotation test.

Important - This is not to say, however, that a bacterial infection may

not be responsible for an animal's problems and clinical signs (e.g. diarrhea, vomiting) ... intestinal bacteria like Salmonella, Clostridia,

Shigella and Campylobacter do cause many illnesses in animals. It is just that

a bacterial problem can not be diagnosed using a fecal float test (i.e. a fecal

float is the wrong test for diagnosing a bacterial disease). In order to diagnose a bacteria-related intestinal disease, a rectal smear (rectal cytology) and a fecal cytology and culture test is required instead of a fecal flotation test.

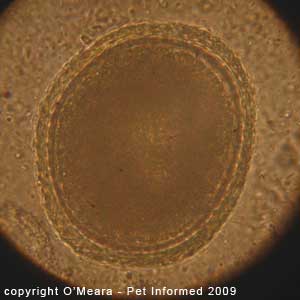

Fecal float parasite pictures 10: A canine roundworm egg (Toxocara canis) seen at a magnification

of 1000x. The microscope magnification setting is 100x - viewed through microscope oil (1000x magnification in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is also taken into account).

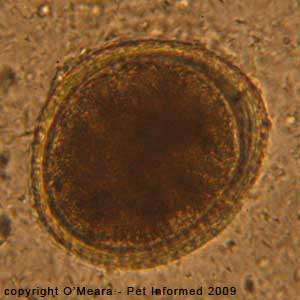

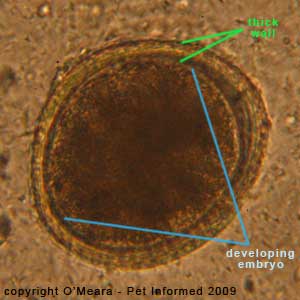

Parasite pictures 11 and 12: A dog roundworm egg (Toxocara canis) seen on a fecal flotation test.

The round worm egg is large, imperfectly round and non-embryonated (non-embryonated means that the worm egg has not yet developed a viable, infective, ready-to-hatch larval worm within the centre of it), with a dark brown centre and a thick, lighter-coloured (orange or yellow coloured) wall, which is not smooth, but pitted and dimpled in appearance. The second image (parasite picture 12)

is labeled to show the thick, pitted wall of the egg and the dark brown bundle of cells

in the middle of the egg, which is the developing worm embryo.

Roundworms in dogs parasite pictures 13 and 14: After the female dog was dewormed, hundreds of adult roundworms

died and were voided in the animal's droppings. This is a shovel-full of the dog's droppings. The large, pale, white worms (roundworms) are clearly visible. A single large handful of the droppings contained over 100 adult round worms - a massive burden.

2) Trichuris vulpis - Canine whipworm eggs (dog whipworm ova) photographed under the microscope.

This section contains photographic images of dog whipworm eggs (Trichuris vulpis), which were discovered on a fecal flotation exam of a dog's stools (droppings).

The fecal float test was performed on the dog (a stray at a shelter) because it was stressed;

had signs of colitis (inflammation of the large intestine characterized by: increased

frequency of defecation; discomfort upon defecation; straining-to-defecate and the passing

of blood-containing, jelly-like, slimy, mucoid, diarrhoeaic feces) and had no history of prior worming. Aside from the sloppy, red, jelly-like feces and the excessively frequent defecation (high urgency of defecation), the dog was otherwise happy and well. As adult whipworm infestations are a common cause

of colitis in dogs, a fecal float examination was considered prudent. The fecal floatation test found that the dog had high numbers of canine whipworm eggs present in its stools. The dog was wormed and tiny, white adult canine whipworms were voided in the faeces. The likely cause of the dog's diarrhea and colitis symptoms was thought to be the whip worm infestation. The dog deworming medication was curative and the colitis and diarrhoea resolved.

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: It is important to mention

that this particular fecal float exam, like all of the others on this page, was performed using sodium nitrate: one of the more common and more readily available fecal flotation solutions

on the market. Textbooks often recommend using fecal flotation solutions with a high specific gravity (like potassium iodide) to float whipworm eggs and, if these solutions are readily available to you, you probably should use them when suspicious of this particular parasite (the results are likely to be better). As this section illustrates, however, if you are unable to access a whipworm-appropriate, high-specific-gravity fecal float solution, don't panic! Just use

the sodium nitrate solution you have. Whipworm eggs can often still be diagnosed using this readily-available fecal float medium.

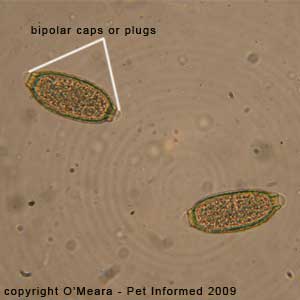

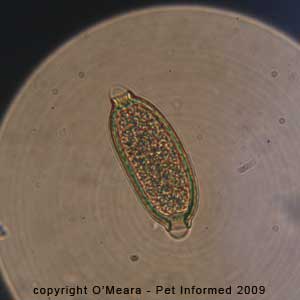

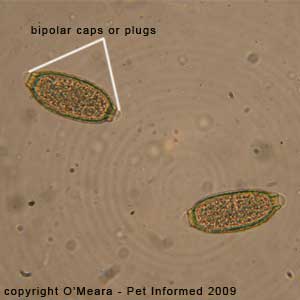

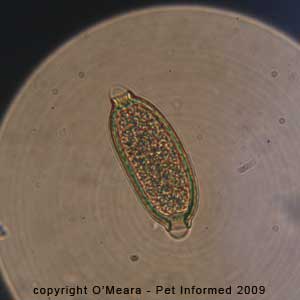

Trichuris vulpis parasite pictures 15 and 16: This is a microscope image of the fecal float test that was performed on the whipworm dog with the diarrhea. Several canine whipworm eggs (Trichuris vulpis species) are visible in these parasite pictures. The dog whipworm eggs are the dark brown, oval-shaped (rugby-ball shaped) structures

seen in the two images. They have thick walls and a pale cap-like structure on each pole.

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 10x (100x in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account).

Dog whipworm eggs pictures 17 and 18: This is another microscope image of a fecal float test that was performed on a whipworm dog with colitis and severe, bloody diarrhea.

The dog's faeces contained large amounts of bright red blood and large amounts of mucus

and slime (jelly-like feces). Many canine whipworm eggs (Trichuris vulpis species) are visible in these parasite pictures. The dog whipworm eggs are the dark red-brown, oval-shaped (rugby-ball shaped) structures seen in the two images. They have thick walls and a pale cap-like structure on each pole.

Canine whipworm eggs photos 19 and 20: These two parasite photos contain close-up images

of a dog whipworm ova (egg) taken at 400x and 1000x (under oil) respectively. The thick walls of the

eggs are clearly visible as are the pale "caps" on each end of the egg (polar caps or "blebs").

Adult canine whipworm image 21: This is an image of three of the adult dog whipworms, which

were voided in the dog's faeces following anthelminthec (worming) treatment. The worms are pale and tiny in size

and two of them show the distinctive whip-like head-end of the worm. The "whip" is the part that

gets imbedded into the wall of the animal's colon.

Adult dog whipworm picture 22: This is a close-up of one of the adult whipworms which was voided in the puppy's feces. The distinctive whip-like anterior of the worm is clearly visible.

Adult dog whipworm images 23: This is an image of the three adult whip worms (Trichuris vulpis) when compared to the size of a 10-cent piece. The worms are tiny and difficult to find in the faeces!

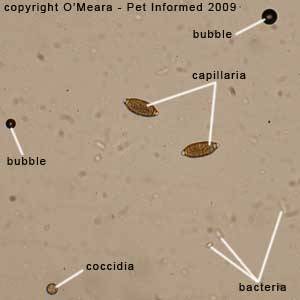

3) Capillaria eggs in a fecal float (an important non-pathogenic parasitic differential diagnosis for dog whipworms).

Fecal Float Hints and Tips:

Some species of animal parasites are incidental findings on a fecal float and

are simply not pathological. It can be very easy, as a veterinarian or animal technician, to get extremely excited when worm eggs or protozoan oocysts are spotted on a faecal float. We love to believe that any organisms seen on a fecal float are diagnostic and sure proof of the reason for an animal's symptoms. It must not be forgotten, however, that, spectacular as they may look under the microscope, some parasites can live within an animal and cause absolutely no symptoms at all simply because they are not disease-causing organisms. Worms like Capillaria (varieties of which can exist in the lungs or intestinal tract of a wide range of animal host species, including dogs and cats) and protozoans like Hammondia, Besnoitia and intestinal Sarcocystis do not cause disease symptoms in animals. Consequently, finding these organisms in a fecal float test does not provide the vet with any deeper clue as to the reasons for an animal's clinical symptoms.

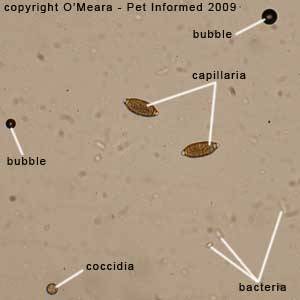

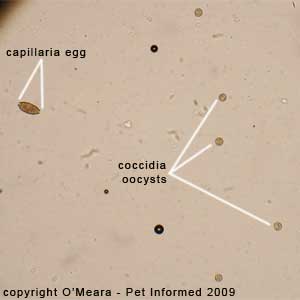

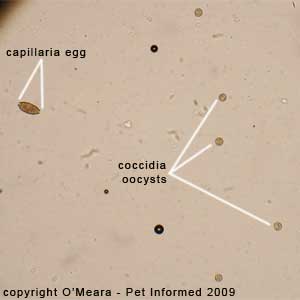

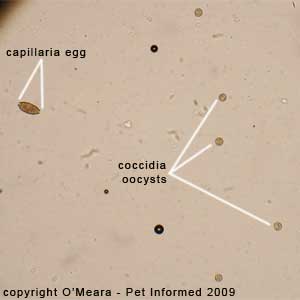

The fecal float images contained in this section were taken from a Currawong (a type of Australian bird)

with diarrhea and severe weight loss. The fecal flotation exam revealed both Capillaria eggs and coccidian oocysts. We know that the eggs are most likely to be Capillaria eggs because

birds do not get whipworms, whose eggs look very similar to those of Capillaria.

As Capillaria are non-disease-causing, the clinical signs seen in the bird were most likely

due to the coccidia protozoan organisms seen in the fecal float or due to some other cause entirely

(note - coccidia can also be an incidental, non-pathogenic finding in some individuals).

Important Author's Amendment (26/8/09): Upon further literature research, the author wishes to amend the information contained in the above paragraph. Although the information contained in the above paragraph

(i.e. that the Capillaria worms are incidental and that the signs of illness seen in the host animal are more likely to be caused by the coccidian organisms than the Capillaria parasites) holds true for

most animal species (e.g dogs, cats), it does not hold true for birds. Although they are generally considered

to be non-pathogenic (non-disease-causing) parasites in most host animal species (e.g. dogs, cats), Capillaria worms can sometimes produce severe signs of clinical disease in many avian (bird) species, including Currawongs. Capillaria worms infest the lining of the intestine, crop and gizzard of affected birds, causing either:

a) acute intestinal injury, hemorrhage and death or

b) chronic intestinal thickening, food malabsorption, severe diarrhea and progressive body wasting (eventually resulting in death).

It thus follows that, in contrast to what was stated in the paragraph above, the clinical signs seen in the bird were just as likely to be caused by Capillaria worms as by the coccidia protozoan organisms also seen in the fecal float. Pet Informed apologises for the oversight.

Had the Capillaria eggs been found in another species of animal (e.g. a dog), they would have been considered to be of little disease significance.

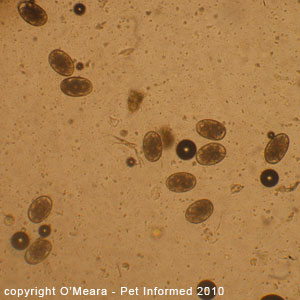

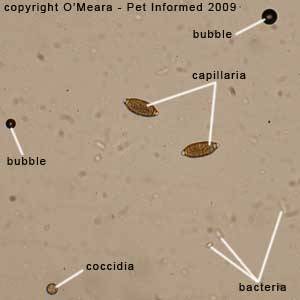

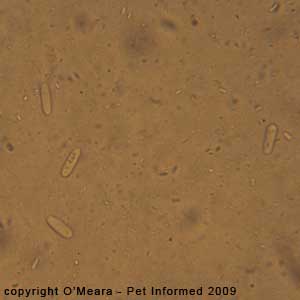

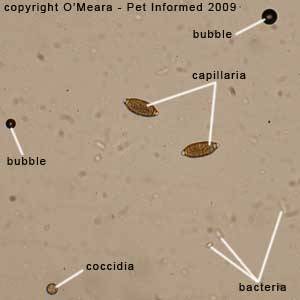

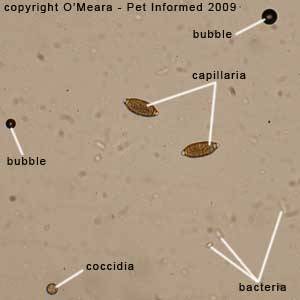

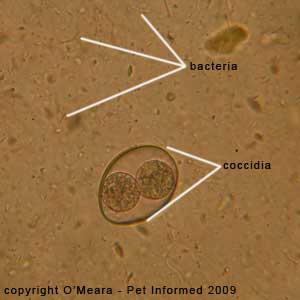

Bird Capillaria eggs pictures 24, 25 and 26: This is a microscope picture of the fecal float test that was performed on the Currawong with the weight loss and the diarrhea. Several Capillaria eggs are visible in these parasite pictures, along with many coccidian oocysts (egg-like

structures produced by coccidia protozoans). The Capillaria eggs are the dark red-brown, oval-shaped (rugby-ball shaped) structures seen in the three images. They have thick walls and a pale cap-like structure on each pole. They look very similar in appearance

to canine whipworm eggs.

Author's note - Capillaria versus whipworm in dogs: Capillaria eggs can occasionally be found in the faeces of a dog that is infested with non-pathogenic Capillaria worms. Capillaria eggs may also appear on a fecal float, which has been performed on the feces of a dog that has been consuming the droppings of other, Capillaria-infested animals

(for example, a dog who had eaten some of this Currawong's droppings might have bird Capillaria eggs appear

in its fecal float). The Capillaria eggs will travel through the dog's intestinal tract unchanged and appear in the canine animal's faeces. These eggs need to be differentiated from those of canine whipworm, which is a pathogenic (disease-causing) parasite in the dog.

Bird Capillaria eggs pictures 27, 28 and 29: This is a close-up microscope picture of the fecal flotation test that was performed on the Currawong with the weight loss and the diarrhea. Several Capillaria eggs are visible in these parasite pictures. The Capillaria eggs are the dark red-brown, oval-shaped (rugby-ball shaped) structures seen in the three images. They have thick walls and a pale cap-like structure on each pole ("bipolar blebs"). They look very similar in appearance

to canine whipworm eggs (Trichuris).

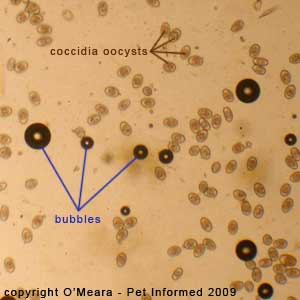

4a) Coccidia in puppies and dogs (canine coccidia protozoan parasites).

This section contains photographic images of canine coccidia (coccidiosis in dogs), which were discovered on a fecal flotation exam of a dog's stools (droppings).

The fecal float test was performed on the dog (a stray puppy at a shelter) because it had watery, slimy, bad-smelling (stinky) diarrhea and because it was stressed; living at an animal shelter

(dog shelters house many dogs of different ages and unknown health background in close proximity

to one another and so the spread of infectious disease is highly possible) and of young age (diarrhea in very young animals is often caused by

diet or by infectious diseases or parasites). The puppy had been wormed with an intestinal "all wormer".

Aside from the sloppy stools and the excessively frequent defecation, the puppy was otherwise happy and well. As canine coccidia infestations are common in young puppies, including "wormed"

puppies, a fecal float examination was considered prudent. The fecal floatation test found that the pup had high numbers of dog coccidia oocysts present in its stools. The puppy

was treated for canine coccidiosis and the diarrhoea resolved.

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: This case reminds us that fecal flotation is always a valuable diagnostic

test to perform on animals with diarrhea, even if those animals have been recently "wormed."

Deworming medications (also called "wormers," "all-wormers" or anthelminthecs) only treat the worm parasites that

they have been designed to kill. They do not kill various other parasites of the intestinal

tract that can cause diarrhea, like: coccidia (Isospora, Eimeria), Toxoplasma,

Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Nor do they

kill some of the worm parasites located outside of the intestinal tract (e.g. lungworm), whose eggs and larvae

will sometimes be voided in the faeces of the affected animal. These other parasites, like the coccidian organisms found in this case, can sometimes be diagnosed on fecal floatation testing.

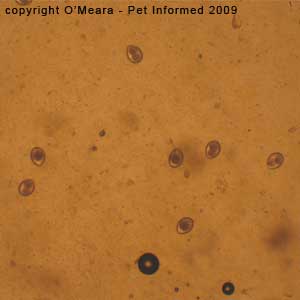

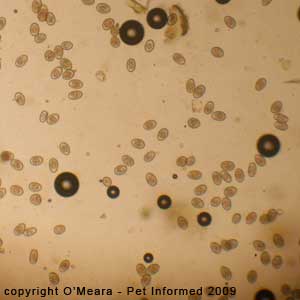

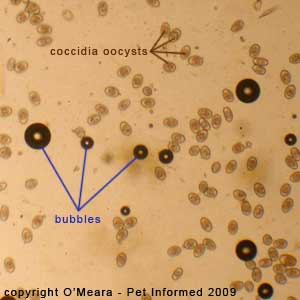

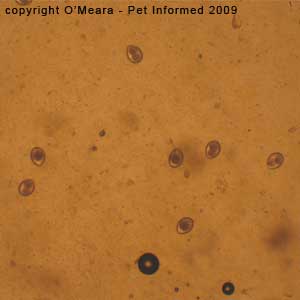

Canine coccidia parasite picture 30: This is a microscope image of the fecal flotation test that

was performed on the young shelter puppy with the diarrhea. Several canine coccidia

oocysts (Isospora species) are visible in the picture. These are the ovoid to circular structures scattered throughout the image. They have a sharp, clearly-defined

outer wall or shell and one or two central clusters of cells called "sporonts" (these are

in the process of maturing and dividing to form infectious structures called sporozoites).

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 10x (100x in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account). Coccidia are about 1/3 of the diameter of a roundworm egg.

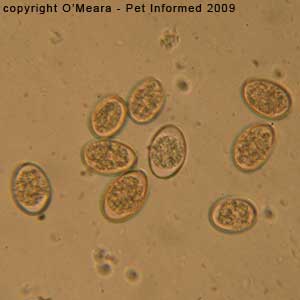

Coccidia in puppies parasite picture 31: This is a close-up microscope image of the fecal flotation test that

was performed on the young shelter puppy with the diarrhea. Two canine coccidia

oocysts (Isospora species) are visible in the picture. These are the ovoid structures in the centre of the image. They have a sharp, clearly-defined

outer wall or shell and one or two central clusters of cells called "sporonts" (these are

in the process of maturing and dividing to form infectious structures called sporozoites).

The oocyst on the left has a single sporont that is in the process of dividing into two sporonts.

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 40x (400x in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account). Coccidia are about 1/3 of the diameter of a roundworm egg.

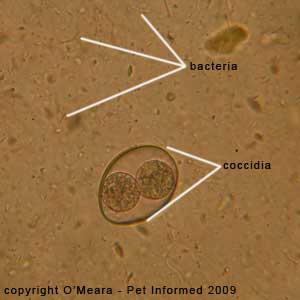

Coccidia in puppies parasite pictures 32 and 33: This is a close-up microscope image of the fecal flotation test that was performed on the young shelter puppy with the diarrhea. One canine coccidia oocyst (Isospora species) with two clearly-visible sporonts is visible in the picture. The oocyst floats within a background of millions of tiny fecal bacteria (bacterial soup).

Author's note: You will always find millions of bacteria on a fecal float. They are natural residents of the colon and are of little diagnostic significance on a fecal flotation test.

Coccidiosis in dogs image 34: This is an extreme close-up microscope image of the fecal flotation test that was performed on the young shelter puppy with the diarrhea. One canine coccidia oocyst (Isospora species) with a single clearly-visible sporont is visible in the picture.

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 100x - under oil (1000x in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account).

Coccidiosis in dogs image 35: This is an extreme close-up microscope image of the faecal flotation test that was performed on the young shelter puppy with the diarrhea. One canine coccidia oocyst (Isospora species) is visible in the picture. Its single sporont

is currently in the process of dividing into two sporonts.

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 100x - under oil (1000x in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account).

If you would like to know more about canine coccidia, visit our great coccidiosis page.

4b) Coccidia in kittens and cats (feline coccidiosis).

This section contains photographic images of feline coccidia (coccidiosis in cats), which were discovered on a fecal flotation exam of a cat's stools (droppings).

The fecal float test was performed on the cat (one of a group of stray kittens at a shelter) because it had soft, slimy, yellowish, custard-consistency, bad-smelling faeces (occasionally containing a streak of fresh blood)

and because it was stressed, living at an animal shelter (cat shelters house many cats of different ages and unknown health background in close proximity to one another and so the spread of infectious disease is highly possible) and of young age (diarrhea in very young animals is often caused by

diet or by infectious diseases or parasites). All of the kittens in the group had the same

problem. The kittens had each been wormed with an intestinal "all wormer", which had not helped.

Aside from the sloppy stools and the excessively frequent defecation, the kittens were otherwise happy and well. As feline coccidia infestations are common in young kittens, including "wormed"

kitties, a fecal float examination was considered prudent. The fecal flotation test found that the cat had high numbers of feline coccidia oocysts (an Isospora species, most likely Isospora felis) present in its stools. Other smaller oocysts of an unknown coccidia species were also found. The kittens were all

treated for feline coccidiosis and the diarrhoea resolved.

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: This case reminds us that fecal flotation is always a valuable diagnostic

test to perform on animals with diarrhea, even if those animals have been recently "wormed."

Deworming medications (also called "wormers," "all-wormers" or anthelminthecs) only treat the worm parasites that

they have been designed to kill. They do not kill various other parasites of the intestinal

tract that can cause diarrhea, like: coccidia (Isospora, Eimeria), Toxoplasma,

Cryptosporidium and Giardia. Nor do they

kill some of the worm parasites located outside of the intestinal tract (e.g. lungworm), whose eggs and larvae

will sometimes be voided in the faeces of the affected animal. These other parasites, like the coccidian organisms found in this case, can sometimes be diagnosed on fecal floatation testing.

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: This case also reminds us that, in "group situations," it is important to medicate and treat all of the animals that have been in contact with the infected animal and not just the animal

that had the fecal float performed.

Feline coccidiosis parasite picture 36: This is a microscope image of the fecal float test that

was performed on the young shelter kittens with the diarrhea. Several feline coccidia

oocysts (Isospora species - likely to be Isospora felis) are visible in the picture. These are the ovoid to circular structures scattered throughout the image. They have a sharp, clearly-defined

outer wall or shell and one or two central clusters of cells called "sporonts" (these are

cellular structures that are in the process of maturing and dividing to form infectious structures called sporozoites).

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 10x (100x in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account). Coccidia are about 1/3 of the diameter of a roundworm egg.

Coccidiosis in cats image 37: This is an extreme close-up microscope image of the fecal flotation test that was performed on the young shelter kitty with the diarrhea. One feline coccidia oocyst (an Isospora species, likely to be Isospora felis) with a single clearly-visible sporont is visible in the picture.

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 100x - under oil (1000x in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account).

Coccidiosis in cats image 38: This is an extremely close-up microscope image of the faecal flotation test that was performed on the young shelter kitty with the diarrhea. A feline coccidia oocyst (an Isospora species, likely to be Isospora felis) with a single clearly-visible sporont is visible in the picture. It is the oocyst on the left.

The parasite on the right of this photo is not Isospora felis (the typical disease-causing

coccidian species infecting cats) - it is too spherical and small to be Isospora felis. It could be another, less common, feline Isospora species: Isospora rivolta, which can also cause disease

in cats. Alternatively, this small oocyst could belong to one of a group of mid-sized non-disease-causing coccidian species infecting domestic cats (e.g. Besnoitia species). Besnoitia species do not cause diarrhea

and do not require treatment.

The small, round oocyst seen on this image (image 38) is unlikely to be from the non-pathogenic

Sarcocystis or Hammondia Genuses of coccidian-type parasites because it

is too big (these parasites are <14um in diameter). For the same reason (it is too big), the oocyst is also unlikely to be a nasty Toxoplasma gondii oocyst either. Toxoplasma is normally <14um in size and very spherical in shape. Toxoplasma is a protozoan parasite that can produce diarrhea (and also other more systemic disease signs) in cats as well as a range of other disease symptoms in people and other animals.

We always look out for it on fecal flotation examinations of cat faeces because it has

human infectivity risks (i.e. it is a zoonotic disease or zoonoses).

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: This image (picture 38) was included because it illustrates how the different Genuses and

species of coccidia-like parasite can have oocysts of different sizes and how, by measuring and

comparing these sizes, we can make an accurate diagnosis of a parasite's Genus and thus a parasite's likely

disease significance. The round oocyst shown in image 38 was not Isospora felis, however, from its large size,

we can say that it was probably an Isospora type and thus of similar diagnostic and disease significance to Isospora felis. The oocyst in question was also large enough to be Besnoitia, a parasite

which wouldn't have caused any disease signs. The most important thing is that the oocyst in question was much too big to be a nasty Toxoplasma or Cryptosporidium oocyst, so there was, thus, little concern about the mystery organism going on to infect people.

Finding significant variations in the shapes and sizes of oocysts should be a clue that different species of protozoan

parasites may be infecting the animal, the significance of which may be minor to severe depending on

the parasite in question. The photo should be a reminder to fecal float technicians to

be open-minded in their microscopic parasite searches. One should not expect all coccidian oocysts to be of a set size - failure to appreciate just how tiny some oocysts can be

can result in smaller oocysts being missed on a faecal float.

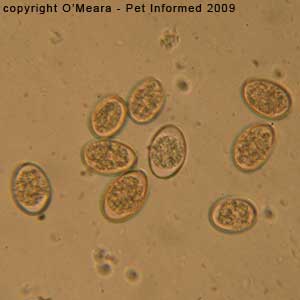

Coccidiosis parasite pictures 39 and 40: These two images are microscope photographs of a fecal float test that was performed on an older cat with diarrhea. They do not come from the same cat as those fecal floatation images preceding them.

The first image (parasite picture 39) contains an oval-shaped coccidian oocyst (inside of circle) with

two sporonts that is probably an Isospora felis type. The second image (parasite picture 40) is taken at the same magnification and contains a very-round, much smaller oocyst (inside of circle),

which is unlikely to be of the same coccidian species as the oocyst in image 39. We know that

the organism in picture 40 is a protozoan coccidia-like oocyst because it has the same structure and

appearance as one (tiny size, sharply-defined wall, sporonts and so on).

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: It should be noted that the Genus and species of an oocyst can not be 100% determined from a fecal flotation image alone. Coccidian oocysts have to be mature and to have

reached their infective, sporozoite-containing stages before a definitive species diagnosis can be made. Thus, the disease-causing significance of these two oocysts is unknown

and can only be surmised.

Author's note: These images were included because they illustrate how different species

of coccidian and coccidia-like parasite can have oocysts of different sizes. Finding significant variations

in the shapes and sizes of oocysts should be a clue that different species of protozoan

parasites may be infecting the animal, the significance of which may be minor to severe depending on

the parasite in question. These two photos should be a reminder to fecal float technicians to

be open-minded in their microscopic parasite searches. Unlike the case with worm eggs

(which are of a more uniform size), one should not expect all coccidian-type oocysts to be of a set size. Failure to appreciate just how tiny some oocysts can be

can result in smaller oocysts being missed on a fecal flotation. A person only expecting to find

an oocyst the size of that shown in image 39 may well overlook tiny oocysts like that pictured

in photo 40.

If you would like to know more about feline coccidia, visit our great coccidiosis page.

4c) Rabbit coccidia - Eimeria.

This section contains photographic images of rabbit coccidia, which were discovered during fecal flotation examinations of the scats (droppings or spore)

of two different rabbits.

Rabbit 1:

The fecal floatation test was performed on one of the rabbits (a young rabbit at a shelter) because it had

marked weight loss and profuse, severe, brown, smelly, watery diarrhoea, which coated its belly and legs

(see image opposite). Aside from the watery stools, the underweight body condition and the excessively frequent defecation, the rabbit was otherwise well, though perhaps a little dehydrated and depressed. As rabbit coccidia infestations are common in young rabbits (especially shelter rabbits), a

fecal float examination was considered prudent. The fecal flotation test found that the bunny had moderate numbers of rabbit coccidia oocysts (Eimeria species) present in its stools. The rabbit was treated for the coccidiosis and the diarrhoea resolved.

The fecal floatation test was performed on one of the rabbits (a young rabbit at a shelter) because it had

marked weight loss and profuse, severe, brown, smelly, watery diarrhoea, which coated its belly and legs

(see image opposite). Aside from the watery stools, the underweight body condition and the excessively frequent defecation, the rabbit was otherwise well, though perhaps a little dehydrated and depressed. As rabbit coccidia infestations are common in young rabbits (especially shelter rabbits), a

fecal float examination was considered prudent. The fecal flotation test found that the bunny had moderate numbers of rabbit coccidia oocysts (Eimeria species) present in its stools. The rabbit was treated for the coccidiosis and the diarrhoea resolved.

Rabbit 2:

The second rabbit had a fecal flotation test performed merely out of curiosity.

Like the first rabbit, it was a young rabbit at a shelter, but, unlike the first rabbit, its droppings were completely normal. The faecal flotation test found that the rabbit had massive numbers of rabbit coccidia oocysts (Eimeria species) present in its stools (far more than the number seen in the first rabbit). The rabbit was not treated for the coccidiosis as it was unaffected by it (presumably, it was an asymptomatic

carrier animal).

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: This case is important because it shows us that merely finding evidence of a parasite (e.g. parasite eggs or oocysts) on a fecal float is no guarantee that the organism

is or will actually cause any signs of disease at all. An animal can be infested with seemingly

massive numbers of parasites (e.g. rabbit 2) and yet show no outward signs of disease.

In these situations, it seems that the individual animal's immunity has a big part to play

in the manifestation of disease signs. Rabbit 1 might be an animal with a poor immune

system (an inability to fight off parasitic disease) or an immune system that has not yet managed to adapt enough to cope with the coccidian organisms present in the gut. Thus

it shows signs of disease, even with fewer organisms present than rabbit 2. Rabbit 2 probably has a great immune system

and can fight off the effects of the coccidia organisms (show no signs of disease) even

though many are present.

Rabbit 2 could easily become like rabbit 1 (showing signs of disease)

if its immune system ability to fight off the coccidia wanes. This could happen if the rabbit

became immune suppressed. Stress, other illnesses, sudden weight loss, malnutrition, unhygienic living conditions, extremes of cold or heat, bullying, immune suppressant drugs and a raft of other immunosuppressant

factors could cause such an effect on rabbit 2. Likewise, rabbit 1 could become like rabbit 2

(immune to the effects of the parasites) if it is supported with anticoccidial medications

and if its immune system was improved through better health, living conditions, good diet and the like.

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: This case is also important because it highlights the risks

posed to other animals by the so-called "carrier state." A completely normal animal can be carrying

and shedding organisms that are infectious to other animals. Such animals, termed

"carrier animals" are important reservoirs of infection for other animals because

they shed infectious organisms (e.g. coccidia) that can make other animals sick, but show

absolutely no clinical signs themselves. An asymptomatic animal like rabbit 2 could be disastrous in

a high-stress, overcrowded production animal facility like a rabbitry (meat or wool production

rabbit farm) because it would be shedding large numbers of coccidia organisms that could make the other rabbits very sick.

Rabbit 1 - fecal float:

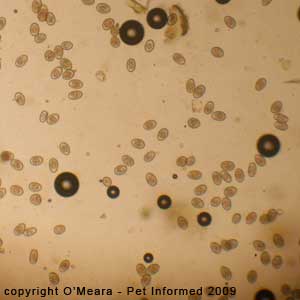

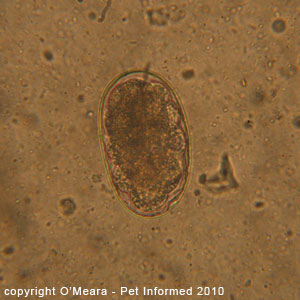

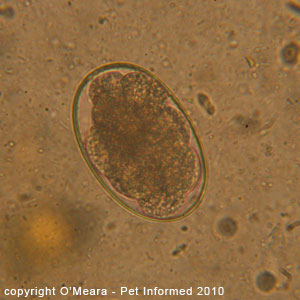

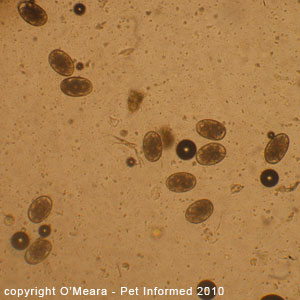

Rabbit coccidiosis 41 and 42: These are microscope images of the rabbit coccidia oocysts

that were found in the fecal float of rabbit 1 (the rabbit with the diarrhea).

Rabbit 2 - fecal float:

Rabbit coccidiosis 43, 44 and 45: These are microscope images of the rabbit coccidia oocysts

that were found in the fecal float of rabbit 2 (the rabbit with no diarrhea). The fecal flotation test

contains almost wall-to-wall coccidian oocysts (far in excess of the numbers seen in rabbit 1).

If you would like to know more about rabbit coccidia, visit our great coccidiosis page.

5a) "Zipper-worm" tapeworms in cats - Spirometra tapeworm eggs and segments.

This section contains photographic images of feline Spirometra tapeworm eggs, which were discovered on a fecal flotation exam of a cat's stools (droppings).

The fecal flotation test was performed on the cat (a stray cat at a shelter) because it was thin, had moderate diarrhea and had no history of prior worming. The fecal flotation test found that the cat had Spirometra tapeworm (otherwise called "zipperworm")

eggs present in its stools. The animal was wormed with an all-wormer tablet, one that included a common tapeworming medication: Praziquantel. Within the day, a large (60cm) Spirometra tape worm (also commonly known as a 'zipper-worm')

was voided in the animal's faeces.

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: This case provides a neat demonstration of how a simple fecal flotation test can lead to the diagnosis, treatment and cure of a parasitic disease.

Spirometra tapeworms are commonly found in shelter cats, many of whom have lead a feral or stray existence. These large tapeworms are caught by outdoor-living cats through the consumption of

killed prey (rodents, reptiles and frogs), which carry the juvenile "spargana" forms of the

tapeworm.

Tapeworms in cats pictures 46 and 47: These are microscope photos of the feline tapeworm eggs

that were found in the fecal flotation test of the stray cat's faeces. The Spirometra eggs are

the dark brown, oval-shaped (rugby-ball-shaped) objects. These eggs have been labeled in image 47.

Tapeworms in cats pictures 48 and 49: These are microscope photos of more of the feline tapeworm eggs

that were found in the fecal flotation test of the stray cat's faeces. The Spirometra tapeworm eggs are

the brown, oval-shaped (rugby-ball-shaped) objects in the photo. There are many cat tapeworm eggs present in these two photos.

Feline tapeworm photo 50: This is a high-power (1000x oil immersion) view of one of the Spirometra tapeworm eggs.

Feline tapeworm photo 51: This is a high-power (1000x oil immersion) view of one of the Spirometra tapeworm eggs.

The egg has a cap-like structure on one end, which is distinctive, called a cap or an operculum. This

has been labeled in this image.

Cat tapeworm picture 52: This is the large, adult Spirometra tapeworm that was voided in the cat's faeces.

Cat tapeworm picture 53: This is the same Spirometra tapeworm that was voided in the cat's feces.

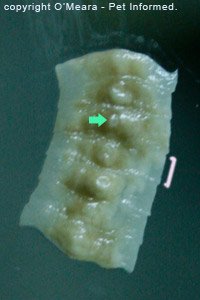

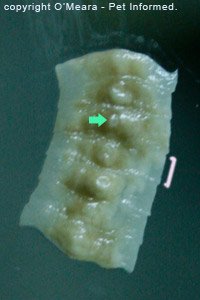

It is a close-up view of the dorsal (top) aspect of the tapeworm, showing off the tapeworm's segments. You should notice the

line of holes running down the centre of the tapeworm's body. These are the tapeworm's "genital pores" - the holes through

which the feline tapeworm voids its eggs. This central line of holes makes the tapeworm look like a zipper: hence the name "zipperworm".

Cat tapeworm picture 54: This is the same Spirometra tapeworm that was voided in the cat's faeces.

It is a close-up view of the ventral (under-side) aspect of the tapeworm, showing off the tapeworm's segments.

Feline tapeworm pictures 55 and 56: These are close-up images of several (seven) of the tapeworm's proglottid segments (a single segment is indicated with a pink bracket in image 56). The green arrow indicates the pore (hole) through which the tapeworm segment voids its eggs.

5b) Feline tapeworm (cat tapeworm) segments - Taenia.

Aside from Spirometra tapeworm eggs (above section - 5a), it is generally uncommon to find the eggs of most cat and dog tapeworm species on a faecal flotation test because these eggs are usually contained within a segment of the tapeworm's body called a proglottid. Tapeworm eggs are rarely found floating freely in the pet's droppings and thus they rarely turn up

on a fecal float.

Tapeworms in pets are generally diagnosed by a gross examination of the pet's feces

rather than by a fecal flotation test. Owners need to examine their pet's droppings and the skin

immediately around their pet's anus for tapeworm segments and individual proglottids (proglottids look like white maggots and freshly-shed ones will seem to move and crawl about like real maggots, too) in order to diagnose tapeworms. If tapeworms are suspected, worming the animal with an all-wormer tablet that contains

the tapeworming medication: Praziquantel, will usually result in the tapeworm or tapeworms

being voided in the pet's faeces.

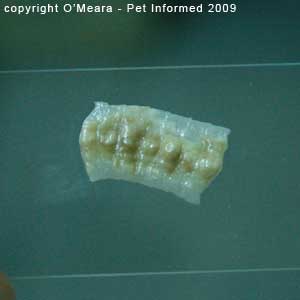

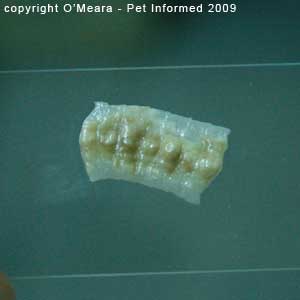

Cat tapeworm parasite pictures 57: This is a microscope slide with a freshly-defecated

length of a feline tapeworm on it. This tapeworm section contains many individual segments called

proglottids. Tapeworm lengths like this one are usually white and flat (like fetuccini pasta) and comprised

of many individual segments (termed proglottids) all stuck together end to end.

Cat tapeworm parasite pictures 58 and 59: These images show a microscope slide with a freshly-defecated

section of a feline tapeworm on it. Coverslips have been placed on top of the dead tapeworm's

body to squash it down. By squashing the tapeworm's body in this way, the tapeworm's

individual segments can be clearly seen.

You should also be able to see that each tapeworm segment contains

two very white circular bodies positioned side by side. Each of these white bodies

is a part of the female reproductive tract where the segment makes its eggs (i.e. ovary). Because every mature segment of a tapeworm has its own set of reproductive organs, that's a lot of eggs which are able to be produced and released into the environment by a mature tapeworm!

The shape and structure of each proglottid sac; the manner in which the proglottid sacs

link end to end; the orientation and number of reproductive organs contained within each proglottid sac

and the number and positioning of the tapeworm's genital pores (the holes through which the

tapeworm segments void their eggs) can all be helpful things to examine when making a diagnosis of a tapeworm's Genus and species. For example, some tapeworm types (e.g. Dipylidium)

have two sets of reproductive organs and two genital pores per proglottid, whereas

certain other tapeworm species have only the one. With Taenia species, the front end of

any one segment is shorter in width than the rear end of the segment that it attaches to, giving

the sides of the tapeworm a jagged appearance. Knowing the Genus or species of the tapeworm in question gives the veterinarian an important clue as to how the animal host caught the parasite in the first

place. For example, Dipylidium is caught by consuming tapeworm-infested fleas (or lice), whereas Taenia tapeworms are caught by preying upon certain animal hosts like rodents and rabbits.

6) Hookworm eggs (Ancylostoma caninum eggs) taken under the microscope.

This section contains photographic images of canine hookworm eggs (strongyle-type eggs), which were discovered on a fecal flotation exam of a dog's stools (droppings).

The fecal float test was performed on the dog (a middle-aged Bull-Arab dog) because it was severely underweight; had black, tarry feces (melaena); had daily vomiting and regurgitation

(black vomit) and had cranial abdominal pain, but no other obvious signs of major abdominal organ or intestinal disease (e.g. no abdominal masses, no palpable foreign bodies, no positive parvo test, no changes suggestive of renal or hepatic disease on the blood panel, no diagnostic clues on radiography or ultrasound).

The animal had presented to the vet clinic as a stray and therefore had no history of prior worming

- this added to suspicion that a worm problem might be a possible cause of the dog's symptoms. The fecal flotation test found that the dog had wall-to-wall hookworm eggs (Ancylostoma species) present in its stools.

Because the canine hookworm eggs were so numerous on the fecal float test (see images below), it was

assumed that hookworm parasites were the most likely cause of the dog's symptoms. Hookworms

feeding on the host animal's blood bite and ulcerate the lining of the small intestine, producing intestinal trauma;

intestinal pain and, in severe cases, black feces and vomitus (fresh blood leaking from hookworm-induced small-intestinal ulcers is digested in the host's small intestine, producing a tarry-colored digesta that, when vomited or passed in the feces, appears black). It is possible that the dog's marked emaciation

(weight-loss) may also have been caused by the severe hookworm parasitism. Severe trauma to the lining of the

intestine can thicken the intestinal wall and reduce the intestine's ability to absorb food-stuffs from the intestinal tract - this results in malnutrition and weight-deterioration.

Author's note - Be cautious when assuming that a parasite seen on a fecal float exam is the sole cause of a host animal's clinical problems:

Even though it seems very likely, on the face of it, that hookworm infestation is the major cause of the above-mentioned animal's problems, as a vet I would be somewhat cautious about saying that hookworm parasites are responsible for 100% of the problems seen in this particular animal. This particular dog was only about 3 years of age and, as a rule, it is generally considered quite unusual for a completely healthy adult host animal to get such a severe, clinical hookworm infestation. Clinically problematic hookworm infestations are usually only encountered in young animals (e.g. puppies).

It is possible the adult dog in question had something else medically wrong with it (e.g. pre-existing stress,

disease or malnutrition), which resulted in suppression of the intestinal tract's immunity,

such that it became possible for the hookworms to achieve such large populations (thus producing clinical signs of hookworm disease). Certainly, as a vet, I would deworm this animal and wait to see if it made a complete and full recovery before

saying that hookworms were the one and only issue at play.

That's not to say that otherwise-normal adult dogs never get clinical hookworm infestations!

The above-mentioned dog may have come from a terrible background. It may have never been wormed. It may have been starved. It may have come from a horrible, hookworm-rife environment where hookworm infestations and environmental hookworm larvae burdens were so high that the dog could not help but get a severe, clinical hookworm infestation. In such a situation, worming the dog and getting it out of the hookworm-infested environment would most likely

be curative. I just make the point above (author's note above) to remind you that severe parasitic disease in adult animals can sometimes be a secondary sign of some other major underlying disease condition.

Canine hookworm egg pictures as seen on fecal flotation: These are microscope images of the fecal float test that

was performed on the emaciated dog with the tarry feces and vomiting. All images contain canine hookworm

eggs (ova) as seen during a fecal float.

Eleven dog hookworm eggs (Ancylostoma caninum species) are visible in the first picture. They are the reddish-brown, oval-shaped (rugby-ball shaped) structures seen throughout the image.

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 10x (100x in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account).

Eight dog hookworm eggs (Ancylostoma caninum species) are visible in the second picture. I have magnified this image

slightly, compared to the first image. The dog hookworm eggs are the reddish-brown, oval-shaped (rugby-ball shaped) structures seen throughout the image.

The third image is a close-up view of four of the dog hookworm eggs. You can see the

oval shape of the eggs very clearly here. The eggs each have a thin wall or shell delineating their

elliptical shape and a cluster of cells (the early embryonic worm) visible in their center.

Canine hookworm pictures as seen on fecal floatation: These are microscope images of the fecal float test that

was performed on the emaciated dog with the tarry feces and the vomiting. All images contain canine hookworm

eggs (ova) as seen during a fecal float. You can see the

oval shape of the canine hook worm eggs very clearly in these photos. The eggs each have a thin, yellowish, refractile wall or shell delineating their elliptical shape. A honey-brown, lobular-shaped cluster of cells (the early embryonic hookworm) is visible within the centre of each of the eggs.

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 40x (400x in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account).

Canine hookworm egg as seen on faecal flotation: This is a highly-magnified microscopic image of a canine

hookworm egg as seen during a fecal float test. You can appreciate the lovely, sharply-outlined, oval shape of the hook worm egg very clearly in this picture. The egg has a clearly-delineated, thin, yellowish, refractile wall or shell giving it its elliptoid shape. A rich-brown, lobed, cluster of cells (the morula stage of development of

the early embryonic hookworm) is visible within the centre of the egg.

Interesting note: The physical appearance of this egg is not specific to the canine hookworm parasite. The canine

hookworm is but one member of a Superfamily of worms termed the Ancylostomatoidea Superfamily. This Superfamily contains a broad range of hookworm species that infest various carnivorous hosts (Ancylostoma, Uncinaria), as well as a few hookworm species (e.g. Bunostomum) that infest ruminant animals. For its part, the Superfamily: Ancylostomatoidea belongs to an even larger Order of nematode worms called the Order Strongylida. This huge Order

encompasses several parasitic worm Superfamilies: Ancylostomatoidea (mentioned above, which contains the dog hookworm parasite); Strongyloidea (which contains various parasitic worms of ruminants and, most importantly, the horse 'strongyle worms': Strongylus vulgaris, Strongylus equinus and Strongylus edentatus

that are of such huge parasitic disease importance to horses) and the Superfamily: Trichostrongyloidea (which contains

many important parasitic worms of significance to livestock farmers - Trichostrongylus, Haemonchus, Cooperia, Ostertagia and Nematodirus among them). All worms in these three Superfamilies (Superfamilies all grouped under the Order: Strongylida) produce eggs that appear very similar to the canine hookworm eggs pictured above. Because of this, worm eggs that have this appearance (ovoid, thin-shelled eggs with a lobulated cluster of embryonic cells in the morula stage of development) are given the general term: "strongyle eggs" to denote that the parasitic worm producing them comes from one of the three major Superfamilies grouped under the Order: Strongylida.

Side note for completeness - Order Strongylida also contains a fourth Superfamily called Metastrongyloidea, however, the worms in this Superfamily (mostly lungworm organisms) do not release strongyle-type eggs

into the feces.

7a) Feline lungworm larvae (cat lung worm) - Aelurostrongylus abstrusus.

This section contains photographic images of live feline lungworm larvae, which were discovered on a fecal flotation exam of a cat's stools (droppings).

The fecal float test was performed on the cat (a stray kitten) because it was emaciated, had severe black, tarry diarrhea, had no history of prior worming and because it was very depressed and unwell. The fecal flotation test found that the kitten had both roundworm eggs (see section 1a for fecal flotation pictures of feline roundworm eggs)

and lungworm larvae present in its stools. The kitten was too sick to survive and a subsequent post-mortem examination found that both adult feline roundworms and severe lungworm infestations were present. As the lungworm infestation was very severe and, as only a couple of roundworms were present, the likely cause of the kitten's illness was thought to be the lung worm infestation and not the roundworms (i.e. the round worms were incidental).

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: This case is important because it shows us that several different parasite species can sometimes be discovered in the one animal using a fecal flotation test. Fecal float technicians should

never get too excited about coming across one type of parasite egg on a fecal float test

as this could cause them to stop looking for (and therefore miss and misdiagnose) proof of other parasites. Despite finding one kind of parasite, the fecal float technician needs to keep going and examining the entire slide systematically so that important parasite evidence is not overlooked and missed.

Although the feline roundworm eggs (picture 60, below) appeared obvious and spectacular-looking

(for a parasitologist at least), the adult roundworms that shed them

were not actually responsible for any or all of the clinical signs of illness seen in the animal (see the post mortem pictures of the kitten's intestines - section 1a). Had the person performing the fecal flotation test stopped at this

point: roundworm diagnosed, he or she would have missed out on spotting the

parasite that was actually causing the disease: the feline lungworm (Aelurostrongylus abstrusus).

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: This case also demonstrates the importance of knowing a bit about one's parasites in order to anticipate what species they are likely to be and where in the host body they are likely to be living. Because the only eggs present on the fecal float test

were roundworm eggs and these do not hatch into larval worms prior to leaving the host animal, we knew

that the live larvae found on the fecal flotation test were not typical roundworms. Hookworms were possible, occasionally known to hatch into live larvae before the fecal float is performed, however, no typical hookworm eggs were discovered on the fecal float, which is very unusual for hookworm. Lungworms seemed the most likely parasite candidates because many species of lungworm are known to exit the lungs as an L1 larva form or as a rapidly-hatching egg and appear in the faeces as live worm larvae. For this reason: understanding the parasites, we knew to focus our post mortem efforts on the animal's lungs and chest.

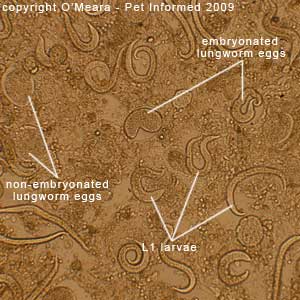

Cat lungworm parasite pictures 60: This is a microscope image of the fecal float test that

was performed on the sick kitten with the diarrhea. Four cat roundworm eggs (Toxocara cati species)

are visible in the picture. They are the dark brown, circular structures on the left of the image. A

shrivelled up lungworm larva (the linear, elongated, clear-coloured object in the upper right corner of the picture) is also visible in this parasite image. Its normally smooth, tapered, worm-like shape has been distorted by the fecal flotation medium (fecal float solution).

Note - the microscope magnification setting is 10x (100x in total when the 10x magnification of the eye-piece is taken into account).

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: Be aware of the effects of salty fecal flotation solutions on the shapes of parasites. These hypertonic solutions suck water from the bodies of larval parasites and free-swimming

parasitic protozoa (e.g. Giardia and Trichomonas), killing them (such that they stop moving)

and also distorting and shrivelling up their outlines (such that they do not look like typical worms

or protozoans anymore). This can make these organisms difficult to identify. For this reason, it is important that fecal flotation tests are examined as soon

as they are performed, so as to reduce the amount of time the parasite spends exposed to the distorting medium.

Feline lungworm pictures 61 and 62: Because the fecal flotation solution distorted and warped

the lungworm larvae somewhat, we decided upon a different technique to help to get pictures of these

parasites under the microscope. Some of the kitten's faeces were dissolved in water (isotonic saline would have also

sufficed) and a drop of this poopy-water was placed on a slide and covered with a

coverslip and examined under the microscope. There were so many lungworm larvae present

within the droppings of this cat that it was easy to spot a number of live larvae swimming through the water. This is what these slides show - live lung worm larvae moving about the slide.

Author's note: Please be aware that not all lungworm infestations are so easy to diagnose

as simply dissolving some poo in water and taking a look. This particular cat was heavily infested

and dying from its parasitism - the worm numbers were so massive they could not be missed. Milder

cases of feline lungworm may require a more advanced fecal exam technique called a Baermann test

or even a tracheal wash (BAL) to make a diagnosis of feline lungworm.

Feline lungworm pictures 63 and 64: These are close-up pictures of the L1 larval stages

of the cat lungworm: Aelurostrongylus abstrusus.

Feline lungworm pictures 65 and 66: These are close-up pictures of the head of one of

the cat lungworm larva. The oesophageal bulb (the distinct bulge-like structure in the centre of the larva's body)

is clearly visible.

Feline lungworm pictures 67 and 68: These are close-up pictures of one of

the cat lungworm larvae. There is a distinct 'hooklike' shape to the tail, which is typical for Aelurostrongylus abstrusus. The hook tends to always stick up, even when

the animal is swimming about.

Cat fecal float pictures 69 and 70: These are microscope images of the fecal float test that

was performed on the sick kitten with the diarrhea. These images illustrate the effects of salty fecal flotation mediums on the shapes of the larval parasites. The sides of the lungworms' bodies have been shriveled up and distorted by the salty fecal flotation solution.

Fecal Float Hints and Tips: Be aware of the effects of salty fecal float solutions on the shapes of parasites. These hypertonic solutions suck water from the bodies of larval parasites and free-swimming

parasitic protozoa (e.g. Giardia and Trichomonas), killing them (such that they stop moving)

and also distorting and shrivelling up their outlines (such that they do not look like typical worms

or protozoans anymore). This can make these organisms difficult to identify. For this reason, it is important that fecal float tests are examined as soon

as they are performed, so as to reduce the amount of time the parasite spends exposed to the distorting medium.

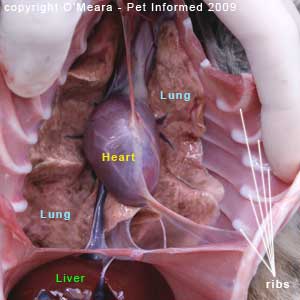

Lungworms in cats pictures 71, 72 and 73: These are post-mortem images taken from the

lung-worm affected kitten. The kitten's lungs should be a lovely, uniform, light-pink colour (salmon-pink), but instead

they are mottled over with a blister-like surface of grey, brown-orange and various shades of pink. Instead of having a nice, smooth pleural surface, these lungs have a roughened surface

covered in fine nodules that look like a series of tiny, firm blisters.

Lungworms in cats pictures 74, 75 and 76: These are post-mortem images taken from the

lungworm infested kitten. The lungs and heart have been removed from the cat's body

and washed prior to being photographed. The pictures show the cat's lungs as a series

of magnified images.

Image 76 is the most spectacular of the images. You can clearly appreciate how the

surface of the lung has been thrown up into a series of grayish coloured, raised nodules.

These raised nodules are not inflammatory nodules. They are actually nests of worm eggs!

The adult lungworm lives deeper within the tissues of the lung (in the lung parenchyme) and she lays her many millions of eggs just beneath the surface layer of the lung. Hence the reason why the lung surface becomes nodular and mottled in this way. The lung nodules

appear grey to whitish in colour, probably because the eggs and worm larvae contained inside of

them are this pale colour.

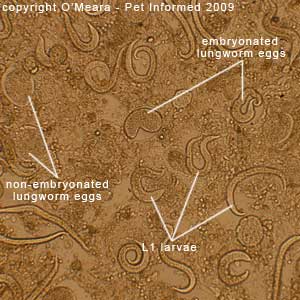

Cat lung worm photos 77, 78 and 79: These are microscope images of what was contained inside of those greyish lung nodules. To get these images, all I did was scrape a scalpel blade back and forth across the

lung surface, opening and macerating some of the raised nodules as I did so. The mush of cell

matter that scraped up onto the blade of the scalpel was smushed onto a microscope slide;

a couple of drops of water was added and a coverslip was placed on top. This is what we saw when we then looked through the microscope ...

What you can see here are lungworm eggs and larvae in various stages of development and hatching. The female lung worm lays eggs within the lung tissue (parasite picture 78 - the non-embryonated eggs). These eggs then develop a larval worm embryo inside of them

(parasite picture 78 - the embryonated eggs - eggs containing a worm). Eventually, the

embryonated eggs hatch, releasing mobile L1 worm larvae (heaps of these live larvae are seen in picture

79). These hatched larvae then migrate through the lung tissue and into the animal's airways, where

they are coughed up, swallowed and voided in the faeces. We then detect them on a fecal float.

You can only imagine the damage that is being done to the lungs in the process!

8) Pictures of multiple parasite infestations seen on the one fecal float.

As has already been discussed at length in various sections of this webpage, it is important to remember that several different parasite species can sometimes be discovered in the one animal using a fecal float test. Fecal float technicians should never get too excited about coming across one type of parasite egg on a fecal flotation test as this could cause them to stop looking for (and therefore miss and misdiagnose) proof of other parasites. Despite finding one kind of parasite (even if there are lots of them), the fecal float technician needs to keep searching and examining the entire slide systematically so that important parasite evidence is not overlooked and missed.

Although the feline roundworm eggs (picture 80, below) are obvious and spectacular-looking

(for a parasitologist at least), the adult roundworms that shed them

were not actually responsible for any or all of the clinical signs of illness seen in the animal. Had the person performing the fecal float test stopped at this point: roundworm diagnosed, then

he or she would have missed out on spotting the parasite that was actually causing the

disease symptoms seen in the patient: the feline lungworm (Aelurostrongylus abstrusus). Likewise, finding

Capillaria eggs in a bird's feces (picture 81, below) seems very spectacular, until you remember

that Capillaria does not actually cause any signs of disease! The disease signs (diarrhea, weight loss)

seen in the bird were more likely to be caused by the coccidian organisms that were also evident (though less

spectacular) on this fecal float.

Important Author's Amendment (26/8/09): Upon further literature research, the author wishes to amend the information contained in the above paragraph. Although the information contained in the above paragraph

(i.e. that the Capillaria worms are incidental and that the signs of illness seen in the host animal are more likely to be caused by the coccidian organisms than the Capillaria parasites) holds true for

most animal species (e.g dogs, cats), it does not hold true for birds. Although they are generally considered

to be non-pathogenic (non-disease-causing) parasites in most host animal species (e.g. dogs, cats), Capillaria worms can sometimes produce severe signs of clinical disease in many avian (bird) species, including Currawongs. Capillaria worms infest the lining of the intestine, crop and gizzard of affected birds, causing either:

a) acute intestinal injury, hemorrhage and death or

b) chronic intestinal thickening, food malabsorption, severe diarrhea and progressive body wasting (eventually resulting in death).

It thus follows that, in contrast to what was stated in the paragraph above, the clinical signs seen in the bird were just as likely to be caused by Capillaria worms as by the coccidia protozoan organisms also seen in the fecal float. Pet Informed apologises for the oversight.

Had the Capillaria eggs been found in another species of animal (e.g. a dog), they would have been considered to be of little disease significance.

Feline fecal float parasite pictures 80: This is a microscope image of a fecal float test that

was performed on a sick kitten with diarrhea. Four cat roundworm eggs (Toxocara cati species)

are visible in the picture. They are the dark brown, circular structures on the left of the image. A

shrivelled up lungworm larva (the linear, elongated, clear-coloured object in the upper right corner) is also

visible in this parasite image.

Bird fecal float picture 81: This is a microscope picture of a fecal float test that was performed on a Currawong with weight loss and the diarrhea. Several Capillaria eggs are visible in this picture, along with many coccidian oocysts (round, distinct-walled, egg-like structures produced by coccidia organisms). The Capillaria eggs are the dark red-brown, oval-shaped (rugby-ball shaped) structures seen in the image. They have thick walls and a pale cap-like structure on each pole (polar blebs). They look very similar in appearance

to canine whipworm eggs.

Cat fecal flotation parasite pictures 82: This is a microscope image of a fecal float test that

was performed on a sick cat with diarrhea. Two different species of coccidian organisms

are present.

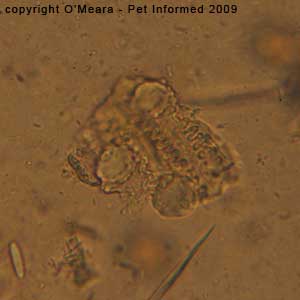

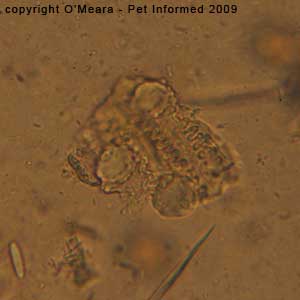

9a) Fecal matter and poo debris on a fecal float.

This section contains photographic images of amorphous fecal matter and cell debris, which are commonly

found during fecal float examinations of animal stools (droppings). I have included these particular

images to show fecal float technicians some examples of objects and artifacts

that are commonly seen during a fecal float exam and which are of no clinical significance and should not be over-interpreted.

Fecal float images 83:

Fecal float images 83: The only parasitic structure present on this image is the coccidia oocyst (contained inside of the white circle). All of the other brown, amorphous material visible on this photo is fecal matter and debris. It is of no

clinical significance.

9b) Pollen.

9b) Pollen.

This section contains some photographic images of pollens, which are commonly

found during fecal float examinations of animal stools (droppings). I have included these particular

images to show fecal float technicians some examples of objects and artifacts

that are commonly seen during a fecal float exam and which are of no clinical significance and should not be over-interpreted.

Fecal floatation pictures:

Fecal floatation pictures: These are images of some pollen balls, which were found

during a fecal flotation exam of a puppy's droppings. They are of no clinical significance.

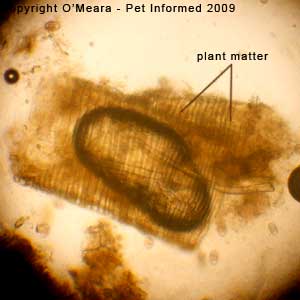

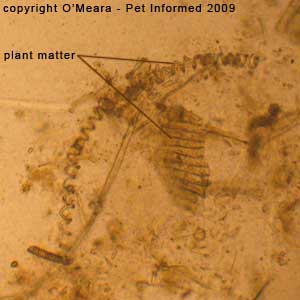

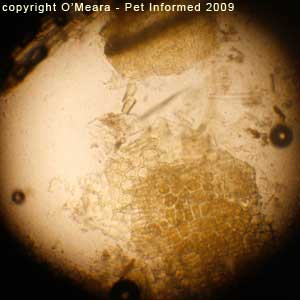

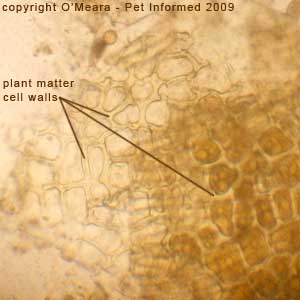

9c) Plant matter.

9c) Plant matter.

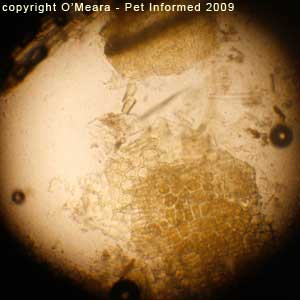

This section contains photographic images of plant matter and plant cell debris, which are commonly

found during fecal flotation examinations of animal stools (droppings). Such plant matter is commonly

found during fecal float examinations of herbivore faeces, but can sometimes be encountered in the

stools of dogs, cats and other carnivores. I have included these particular

images to show fecal float technicians some examples of objects and artifacts

that are commonly seen during a fecal float exam and which are of no clinical significance and should not be over-interpreted.

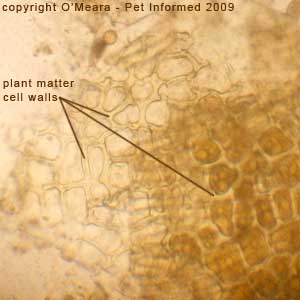

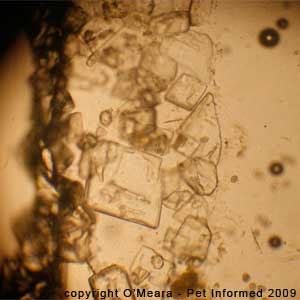

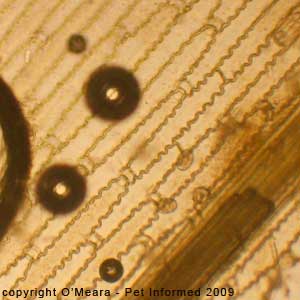

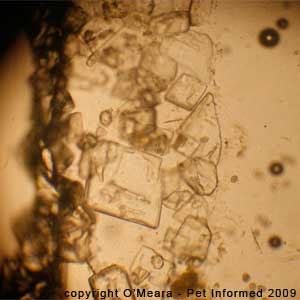

Fecal float images 84, 85 and 86:

Fecal float images 84, 85 and 86: There are no parasitic structures present on these images.

These photos all contain a cross-section-view of a piece of plant matter, as seen on a fecal float. The tough, rigid plant-cell walls, which give plants their strong structures,

are clearly visible in this image. Plant matter on a fecal float is usually of no clinical significance, although

it might give veterinarians a clue as to whether carnivorous animals are eating

vegetation (this can cause tummy upsets in some animal patients).

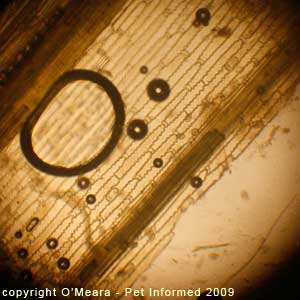

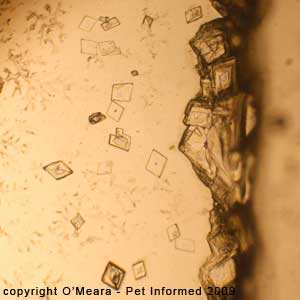

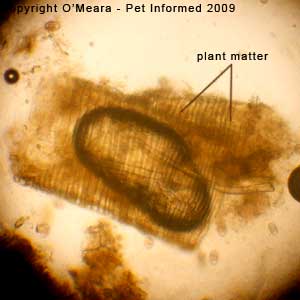

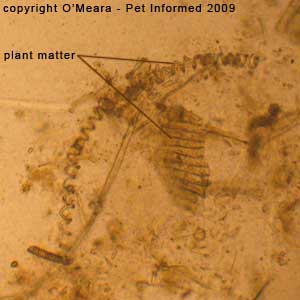

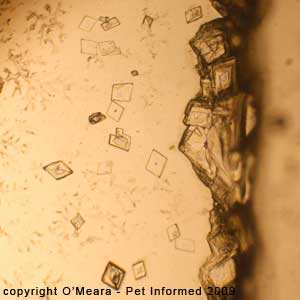

Fecal float images 87, 88 and 89:

Fecal float images 87, 88 and 89: There are no parasitic structures present on these images, aside

from some out-of-focus

Eimeria coccidia present in images 87 (especially seen in the lower right corner) and 88.

These photos contain images of plant materials that are orientated at 90-degrees (i.e. viewed longitudinally)

to those in pictures 84-86. Hence, the tough, rigid, plant-cell walls, which give plants their strong structures,

appear elongated (i.e. as long, rectangular cells) in this image, rather than as the circular, end-on, honeycomb

appearance seen in pictures 84-86. Plant matter on a fecal float is usually of no clinical significance, although

it might give veterinarians a clue as to whether carnivorous animals are eating

vegetation (this can cause gut upsets in some animals).

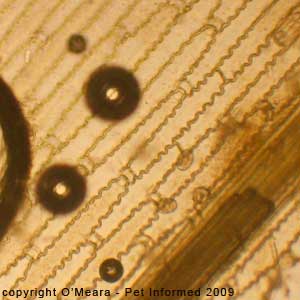

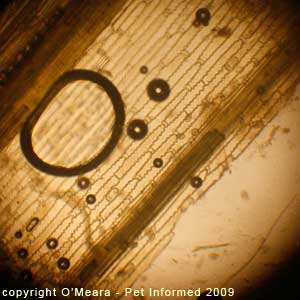

Fecal float images 90 and 91:

Fecal float images 90 and 91: There are no parasitic structures present on these images, aside

from three coccidia oocysts present in image 91 (these are visible through the plant matter).

These photos contain images of plant matter that are orientated at 90-degrees (i.e. viewed longitudinally)

to those in pictures 84-86. Hence, the tough, rigid, plant-cell walls, which give plants their strong structures,

appear elongated (i.e. as long, rectangular cells) in this image, rather than as the circular, end-on, honeycomb

appearance seen in pictures 84-86. Interestingly, the cell walls of this particular vegetation

are thin and wavy in structure, not thick and straight, which probably helps to give this

part of the plant (grass?) some flexibility and bend.

Fecal float images 92 and 93:

Fecal float images 92 and 93: Some more plant matter on a fecal float.

9d) Bubbles.

9d) Bubbles.

This section contains photographic images of air bubbles, which are commonly