Veterinary Advice Online - Taenia Tapeworm Life Cycle.

The tapeworm Genus

Taenia comprises many different important species of tapeworm parasite infesting dogs, cats, humans, rodents and livestock animal species.

Species of parasitic Taenia tapeworms important to human and animal medicine include:

Taenia saginata (known as 'the beef tapeworm') - the adult form of the tapeworm resides in the human intestine

(technically making it as much a human tapeworm as a 'beef' or cattle tapeworm) and the juvenile stage of the tapeworm (the stage of the tapeworm life cycle contagious to humans) resides in the muscles or meat of cattle (and to a lesser extent buffalos, llamas, giraffes, sheep, goats and certain deer species);

Taenia solium (the pork tapeworm) - a very dangerous tapeworm species whose adult form resides in the human gut and whose lethal juvenile or larval form resides in the muscles and organs of pigs and people

(this page contains loads of information on the dangerous Taenia solium pork tapeworm so read on);

Taenia pisiformis - a canine tapeworm whose larval form is carried by rabbits and hares;

Taenia ovis - a canine tapeworm whose larval form is carried in the muscles and hearts of sheep;

Taenia taeniaeformis - a tapeworm in cats whose larval form is carried by rodents such as rats, muskrats and voles;

Taenia hydatigena - a canine tapeworm whose larval form is carried by sheep, goats, pigs, cattle, deer and wild livestock ungulates;

Taenia multiceps - a canid (dog and dog-related species) tapeworm whose larval form is

generally carried in the brains of sheep and goats (occasionally horses, rabbits and cattle);

Taenia crassiceps - a tapeworm of foxes or dogs whose juvenile stages are generally carried by rodent animals;

Taenia serialis - a fox and dog tapeworm carried by rabbits, hares or rodents.

Taenia brauni - a fox and dog tapeworm carried by gerbils.

The different species of Taenia all tend to be very species specific with regard to the animal hosts, both definitive

and intermediate (intermediate hosts and definitive hosts are discussed in section 1), that they will actively

infest. For example, Taenia saginata: the beef tapeworm, will only infest humans (definitive host)

and, for the most part, cattle (intermediate host). Likewise, Taenia pisiformis: one of the two major 'rabbit tapeworms', will only infest canine species (definitive host) and rabbits (intermediate host). Having said this, despite there being vastly differing kinds of host animals involved in each of the Taenia species' life cycles, the overall two-host life cycle structure of the various Taeniid species does seem to be similar in all cases. For this reason, the different Taenia species can all be discussed using a common Taenia life cycle diagram, which is what I have chosen to do (see section 1).

This Taenia tapeworm life cycles page contains a detailed, but simple-to-understand explanation of the

complete Taeniid tapeworm life cycle. It comes complete with a full tapeworm life cycle diagram, which includes

the life cycles of each of the major Taenia species infesting dogs, cats, people, rodent and livestock animal species. Detailed explanation of the Taenia life cycle is included, with mention made about each of the individual

Taenia species where applicable. Info on tapeworm symptoms and the significance of tapeworm infestation in both definitive

and intermediate host animals is included as well as information on treating and managing tapeworm infestations

in these hosts. In the final section (section 4) you'll find extensive information about the Taeniid tapeworms infesting humans, in particular the nasty pork tapeworm (T. solium) and the more benign beef tapeworm (T. saginata).

The Taenia Tapeworm Life Cycle - Contents:

1) The Taenia tapeworm life cycle diagram - a complete step-by-step diagram of the various

common Taenia tapeworm species infesting pet animals (dogs, cats) and people and their transmission via intermediate livestock and wild animal hosts.

Human tapeworm infestation

and the development of adult Taenia saginata and Taenia solium tapeworm burdens is discussed, as is

the life-threatening condition caused by infestation with larval forms of the Taenia solium pork tapeworm: human 'cysticercosis'.

2) Taenia tapeworm symptoms and outcomes - the significance of Taenia infestations in intermediate and definitive host animals.

2a) Tapeworm symptoms in intermediate hosts.

2b) Tapeworm symptoms in definitive hosts.

3) Treatment and prevention of Taeniid tapeworm infestations in definitive host pets (dogs and cats).

This section contains information on the drugs and medications used to treat tapeworms in dogs and cats.

4) Some basics on human tapeworm infestations and the prevention of tapeworm disease (especially pork tapeworm cysticercosis) in people.

4a) Tapeworms in Humans 1 - Taenia saginata beef tapeworm.

4b) Tapeworms in Humans 2 - Taenia solium pork tapeworm.

4c) Tapeworms in Humans 3 - accidental, opportunistic human tapeworm infestations with other Taenia species.

A link to a small page on Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworms in cats.

1) The Taenia Tapeworm Life Cycles Diagram:

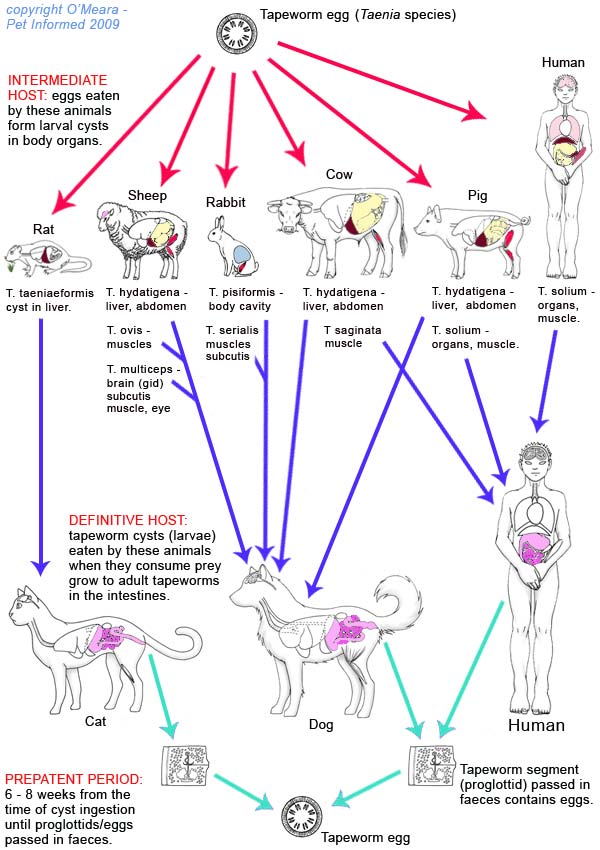

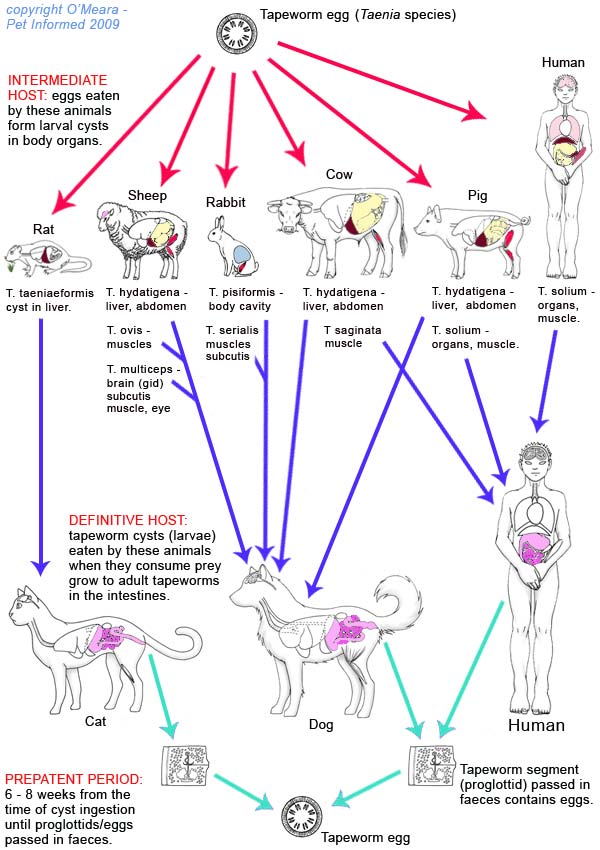

Taenia tapeworm life cycle diagram: This is a diagram of the life cycle of a typical Taenia tapeworm.

The diagram shows the complete cycle of a Taeniid tapeworm's existence - from egg to adult tapeworm to egg again (with the next generation of tapeworm eggs) - within the bodies of two different, yet both equally essential, host animal species:

1. the intermediate host animal and

2. the definitive

host carnivore (dog, cat or man).

Most major species of Taenia tapeworm are included in the diagram. By following the arrows,

you can see which species of intermediate and definitive host animals each of the different Taenia species

predominantly infests. For example: Taenia ovis infests the sheep and the dog. Taenia hydatigena infests a variety of hooved livestock intermediate host species (cattle, sheep, pigs), as well as the dog (definitive host). I elected to insert Taenia multiceps only underneath the sheep intermediate host because, even though cattle, rabbits and horses can be intermediate hosts for this Taeniid species, the sheep is by far

the predominant intermediate host.

The diagram also indicates which parts of the animal body the two main tapeworm stages (the juvenile or larval

stage, which infests the intermediate host animal, and the adult stage, which infests the definitive host animal) occupy.

This organ-trophism (organ localisation) is particularly important to know with regard to the intermediate host (larval) stage of a Taenia tapeworm species because some understanding of the organs that are typically occupied by the tapeworm larva (e.g. liver, brain, muscle, eye, skin) will provide an important clue as to the tapeworm disease symptoms that might be expected in that intermediate host animal. For example, Taenia multiceps preferentially infests the brain of the intermediate host sheep, so

infested sheep could be expected to show signs of profound neurological disease (weakness, loss-of-balance, paralysis, circling, head-pressing, fitting, death). Knowing which intermediate host organs could carry the infective juvenile tapeworms is also important in preventing the definitive host animal from contracting adult tapeworms. If we know the intermediate host organs that must be consumed if the definitive host animal is to contract the adult tapeworms, then we can take steps to prevent such tapeworm transmission by preventing the definitive host animal from consuming such intermediate host body parts. For example, dogs catch the adult form of Taenia multiceps by eating the brains and muscles of infested sheep.

The Adult Tapeworm in the Definitive Host:

Various species of adult Taenia tapeworms live and feed in the small intestines of such host animals as the dog,

cat and human. These carnivorous host animals are termed definitive hosts with regard to their respective

Taenia tapeworm life cycles because they are the hosts that their parasitic Taenia tapeworm species was intended for and that the tapeworm organism reaches adulthood and sexual maturity in. For example, the human is

the definitive host animal for the Taenia solium and Taenia saginata tapeworms, not the dog nor the cat. The cat is the sole definitive host animal for Taenia taeniaeformis.

The body of an adult Taeniid tapeworm is made up of hundreds to thousands of individual segments, termed proglottids. These segments progress in size and maturity as one travels down the tapeworm's body: ranging from very tiny (those proglottids nearest the scolex or 'head' of the tapeworm) right through to very large (easily seen with the naked eye).

Every individual tapeworm segment is essentially an individual egg-producing reproductive factory. Tapeworms are hermaphrodites (bearing both male and female sex structures). Each proglottid segment has its own

testicular-type organ structure/s and its own uterine organ structure/s (for creating and maturing eggs)

and every single proglottid is, therefore, capable of producing and fertilising its own set of eggs, once mature. The small-sized proglottids nearest the anchoring 'head' of the Taenia tapeworm are the most under-developed and immature of all the tapeworm's segments and are, consequently, incapable of creating fertile eggs because of their under-developed state. The large proglottids nearest the 'tail-end' of the Taenia tapeworm are the most mature of all the tapeworm's segments and are capable of having their eggs fertilized and matured into an embryo-bearing state.

Every individual tapeworm segment is essentially an individual egg-producing reproductive factory. Tapeworms are hermaphrodites (bearing both male and female sex structures). Each proglottid segment has its own

testicular-type organ structure/s and its own uterine organ structure/s (for creating and maturing eggs)

and every single proglottid is, therefore, capable of producing and fertilising its own set of eggs, once mature. The small-sized proglottids nearest the anchoring 'head' of the Taenia tapeworm are the most under-developed and immature of all the tapeworm's segments and are, consequently, incapable of creating fertile eggs because of their under-developed state. The large proglottids nearest the 'tail-end' of the Taenia tapeworm are the most mature of all the tapeworm's segments and are capable of having their eggs fertilized and matured into an embryo-bearing state.

Author's note: because each individual proglottid segment can reproduce sexually on its own, some texts have described tapeworms as being almost like a colony (a large 'super-organism' made up of many individuals: each capable

of living and reproducing without much assistance from the whole). Unlike a true colony, however, the individual reproductive segments of a tapeworm can not exist completely independently as individual units away from the whole. The individual tapeworm segments all rely on the survival and intestinal-attachment of the tapeworm's head if they are to remain within the definitive host animal and survive. Also, there is but one nervous system, under the control of the tapeworm head, linking all of the proglottids together in the tapeworm chain (i.e. the individual proglottid reproductive units are not so independent that they have been given their own individual nervous systems and brains).

Author's note: Because every individual proglottid contains both male and female sex organs, it is possible for a single proglottid to 'self-fertilise' (self-inseminate its own eggs). And this

certainly does occur. In reality, however, it is probably much more common for individual proglottids to 'cross-fertilise' - inseminating other, nearby proglottids on the same tapeworm 'chain' and/or even proglottids located on completely separate tapeworms (i.e. other mature Taenia tapeworms that just happen to be living within reach). This makes for a better spread of tapeworm genes and lessens the degree of in-breeding.

When a proglottid enlarges and develops to a certain stage, becoming sexually mature, gametes (essentially sperm) from the male testicular components of the proglottid

segment fertilize the eggs (female) present within that or a nearby proglottid segment (as mentioned before, there can be cross-fertilisation from proglottid to proglottid). The newly fertilized tapeworm eggs mature

inside of the proglottid, developing embryos inside of them, and the proglottid continues to grow in size. A proglottid that contains fertilized eggs inside is said to be "gravid" (i.e. a gravid proglottid).

When a proglottid enlarges and develops to a certain stage, becoming sexually mature, gametes (essentially sperm) from the male testicular components of the proglottid

segment fertilize the eggs (female) present within that or a nearby proglottid segment (as mentioned before, there can be cross-fertilisation from proglottid to proglottid). The newly fertilized tapeworm eggs mature

inside of the proglottid, developing embryos inside of them, and the proglottid continues to grow in size. A proglottid that contains fertilized eggs inside is said to be "gravid" (i.e. a gravid proglottid).

Once the fertilised tapeworm eggs are fully-matured (ready to enter the next stage of the Taenia tapeworm life cycle), the now-enlarged, fat proglottid segment bearing them breaks away from the main body of the tapeworm.

This proglottid segment exits the definitive host animal's body intact via the anus. The segment either physically

crawls from the anus of the host animal by contracting its muscles and creeping along (people spotting these crawling

proglottid segments often think that their pet is infested with fly maggots) or it is voided in the animal's stools as the pet defecates. Sometimes a large section of the Taenia

tapeworm (several proglottids in length) breaks away and is voided in the feces. These longer sections

are almost invariably found by pet owners, sometimes causing alarm, particularly if the pet toilets in

a litter tray that the owner has to clean.

Once out in the environment, the shed proglottid segment continues to writhe, breaking apart and expelling its fertilized, matured tapeworm eggs into the environment as it does so. Taeniids lack

a pore for the eggs to come out of and so the proglottid needs to physically split open to release them.

The eggs of Taenia tapeworm species are expelled from the proglottid segment as individuals.

Each egg is infective the moment it exits the proglottid and generally contains an embryo (called a hexacanth) that has the potential to develop into an adult Taenia tapeworm at some point in the future (all going to plan with regard to the life cycle requirements of that individual Taenia species, of course).

The Juvenile Tapeworms Enter and Occupy the Intermediate Host:

An intermediate host animal that is specifically suited to the particular species of Taenia tapeworm in question (usually a livestock animal, such as a sheep, pig or cow, or a wild animal species, such as a wild ungulate, rabbit or rodent) consumes the Taeniid tapeworm eggs that have been shed into the environment.

These tapeworm eggs are typically consumed in a pasture or forest-type environmental setting. The infested definitive host animal defecates

onto the pasture (e.g. pasture on a farm) or in the forest (e.g. bushland, national park setting) and, in doing

so, sheds infective tapeworm eggs into this environment. The organic fecal matter breaks down in days, but the resistant

tapeworm eggs remain in the environment, speckled invisibly across the grass. The intermediate host animal

consumes the tapeworm eggs, thereby becoming infested, by eating the contaminated pasture contained within this forest or

farmland setting. On some occasions, an intermediate host animal may even consume an entire, freshly-shed, gravid

proglottid (e.g. through the ingestion of fresh definitive host feces - which cows and pigs apparently like to snack on), resulting in the uptake of hundreds of eggs all at once by that intermediate host.

Aside from pasture contamination, tapeworm eggs (termed oncospheres) can also find their way into intermediate host animals via the contamination of waterways with tapeworm-infected feces (the intermediate host animal drinks the contaminated water and ingests the tapeworm eggs). Crops, vegetables and fruits fertilised with untreated sewage or

effluent (e.g. human effluent, animal effluent) can also become diffusely contaminated with tapeworm

eggs, which can then make their way into intermediate host animals through the consumption of these crops.

Finally, insects (e.g. flies) and rodents can transfer the tapeworm eggs to the intermediate host via their feet

(e.g. a fly lands on tapeworm-infected poo, picks up tapeworm eggs on its feet and then flies to the food of the intermediate host where its walking transfers the eggs onto the intermediate host's meal).

Aside from pasture contamination, tapeworm eggs (termed oncospheres) can also find their way into intermediate host animals via the contamination of waterways with tapeworm-infected feces (the intermediate host animal drinks the contaminated water and ingests the tapeworm eggs). Crops, vegetables and fruits fertilised with untreated sewage or

effluent (e.g. human effluent, animal effluent) can also become diffusely contaminated with tapeworm

eggs, which can then make their way into intermediate host animals through the consumption of these crops.

Finally, insects (e.g. flies) and rodents can transfer the tapeworm eggs to the intermediate host via their feet

(e.g. a fly lands on tapeworm-infected poo, picks up tapeworm eggs on its feet and then flies to the food of the intermediate host where its walking transfers the eggs onto the intermediate host's meal).

Author's note: You will notice that man is also listed on the above diagram as an intermediate

host for the Taenia species: Taenia solium (pork tapeworm). Humans infested with adult Taenia solium tapeworms can ingest their own tapeworm eggs or pass them on to other unwitting people, if they do not exercise good hygiene after using the bathroom (i.e. good hand-washing). Poor hygiene, resulting

in the consumption of microscopic amounts of egg-contaminated human feces, can result in humans

becoming the intermediate hosts of the pork tapeworm (in place of the usual intermediate host, which is

the pig). This is very dangerous for the human who gets infested in such a way, as the

intermediate tapeworm forms (termed cysticerci) can invade important internal organs like the lungs and brain,

resulting in disease, disability and even death.

When the intermediate host animal consumes the tapeworm egg/s, the tapeworm embryos contained inside of these eggs survive and hatch from their eggs within the intestines of the intermediate host animal. The tapeworm embryos (termed hexacanths, but also called first stage larvae) migrate across

the intestinal wall and establish themselves within the organs of the intermediate host animal. Organs chosen for this larval invasion vary depending on the Taenia species involved.

Some species of Taenia larvae invade only a limited range of tissues. For example, Taenia saginata and Taenia ovis favour muscle tissues, including the heart. Taenia taeniaeformis invades the liver. Other species of Taenia invade a much

broader range of organs (making them very dangerous to the host). For example, Taenia solium larvae

will preferentially invade the liver, lungs, brain and muscle, but any part of the host body can, theoretically, be infested (e.g. bone marrow, mesentery, eye). This is what makes Taenia solium such a dangerous, life-threatening parasite for the intermediate host.

When the intermediate host animal consumes the tapeworm egg/s, the tapeworm embryos contained inside of these eggs survive and hatch from their eggs within the intestines of the intermediate host animal. The tapeworm embryos (termed hexacanths, but also called first stage larvae) migrate across

the intestinal wall and establish themselves within the organs of the intermediate host animal. Organs chosen for this larval invasion vary depending on the Taenia species involved.

Some species of Taenia larvae invade only a limited range of tissues. For example, Taenia saginata and Taenia ovis favour muscle tissues, including the heart. Taenia taeniaeformis invades the liver. Other species of Taenia invade a much

broader range of organs (making them very dangerous to the host). For example, Taenia solium larvae

will preferentially invade the liver, lungs, brain and muscle, but any part of the host body can, theoretically, be infested (e.g. bone marrow, mesentery, eye). This is what makes Taenia solium such a dangerous, life-threatening parasite for the intermediate host.

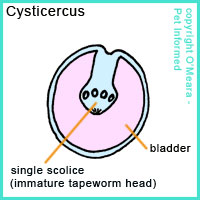

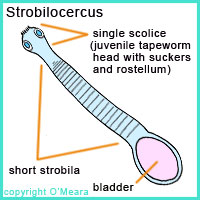

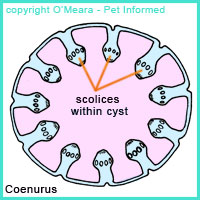

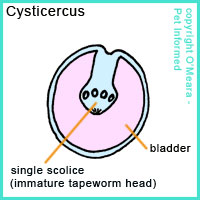

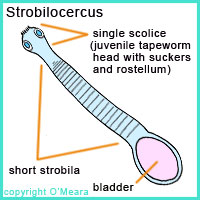

Once established in a chosen site, the Taenia tapeworm hexacanths (first stage larvae) develop and enlarge further into an intermediate larval tapeworm stage called a tapeworm cyst (termed a second stage larvae), the form of which (cysticercus, strobilocercus or coenurus - see diagrams and explanations below) depends on the Taenia species involved. From now on, when I mention cystic, juvenile or larval tapeworms present in intermediate host body tissues, assume I am talking about the stage two larval form of the Taeniid parasite.

The speed of development of the second stage larval form is variable between the different Taenia species. Taenia saginata takes about 2 months for the invading hexacanth (stage 1 larva) to transform into a cysticercus (stage 2 larva).

Note on terminology: an intermediate host animal (e.g. sheep, cow, rabbit and so on) is a host

animal that the respective Taenia tapeworm parasite needs to infest if it is to be able to complete an essential part of its lifecycle. In this case, the Taenia tapeworm needs to infest an animal host (generally a herbivore or omnivore) if it is to hatch from the tapeworm egg and transform into a second stage larval cyst. The parasitic tape worm is unable to reach adulthood and sexual maturity inside of the intermediate host animal and needs to later enter the body of a definitive host animal like a dog, cat or person in order

to achieve sexual and reproductive maturity.

The larval tapeworm cyst of most Taenia species takes on the form of a spherical, expanding, fluid-filled, bladder-like structure with a thin, almost-see-through, outer wall (at surgery or post-mortem evaluation, Taenia cysts look a bit like small, white-to-transparent water-balloons). The cysts are usually found imbedded in the tissues and organs of the intermediate host animal. The cysts are typically small (a few centimetres in diameter), but occasionally

Taenia cysts will be found that are quite large (around 10-20cm or more) in size. The size of the cyst

depends on the species of the Taenia tapeworm (e.g. T. saginata cysts are usually small - about 10mm diameter); the length of time it has been present in the host's tissues (larger sizes may be attained with more time) and the structural form of the cyst (cysticercus, strobilocercus or coenurus - see diagrams below). On the diagrams below - the wall of the cyst or 'bladder' is colored pale blue and the fluid center is coloured in pink.

The inner lining of the cyst or 'bladder' is called a "germinal lining". It actively

generates within the cystic confines one (e.g. cysticercus or strobilocercus forms) or more (e.g. coenurus forms) miniature larval tapeworm head/s (these tapeworm heads are termed 'scolices or protoscolices). These tiny tapeworm 'heads' (labeled as scolices on the diagrams below) are the individuals that become the adult tapeworms when the Taeniid cyst is later consumed by the definitive host animal (dog, cat, man). They have most of the physical structures that are present on an adult tapeworm head, including suckers ('acetabulums')

and a hooked attachment structure called a 'rostellum' (note - some species of adult Taenia lack a rostellum so their juvenile forms won't bear this structure either).

There are three main structural forms that a Taeniid cyst can exhibit, with each species of Taenia tapeworm taking on just one of the three forms. A Taenia species will have only one form of intermediate host cyst - it will not alternate between the different types of larval cyst within that one species.

The first larval cyst form is the cysticercus (image 1, below). It is basically a bladder-like cystic structure with a single scolice contained inside. A single tapeworm egg ingested by the intermediate host animal will result in the formation of a single cyst containing a single scolice within the intermediate host (i.e. one scolice that is infective to the definitive host animal and which will result in the formation of one adult tapeworm). Taenia

saginata, Taenia solium, Taenia hydatigena, Taenia pisiformis, Taenia crassiceps, Taenia hydatigena and Taenia ovis all use cysticercus forms of juvenile tapeworm cyst and the infestation

of the intermediate host, when it occurs, is termed: cysticercosis.

The second larval cyst form is the strobilocercus (image 2, below). Similar to the cysticercus, the strobilocercus is basically a bladder-like cystic structure with a single scolice. Unlike the cysticercus, the scolice of the strobilocercus seems to be more well-developed, containing a good

length of body (strobila) behind the head or 'scolex' structure. As with the cysticercus, a single tapeworm egg ingested by the intermediate host animal will result in the formation of a single scolice within the intermediate host (i.e. one scolice that is infective to the definitive host animal and which will result in the formation of one adult tapeworm). Taenia

taeniaeformis uses a strobilocercus form of juvenile tapeworm cyst.

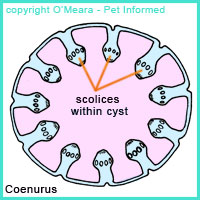

The third larval cyst form is the coenurus (image 3, below). Similar to the cysticercus, the coenurus is basically just an expanding, bladder-like cystic structure, except that it contains numerous scolices, not just one. With the coenurus, a single tapeworm egg ingested by the intermediate host animal will result in the formation of a single cyst containing

multiple scolices within the intermediate host animal (i.e. many scolices that are infective to the definitive host animal and which will result in the formation of several adult tapeworms upon

consumption by the definitive host animal). Taenia multiceps, Taenia serialis and Taenia brauni use a coenurus form of juvenile tapeworm cyst.

Taenia tapeworm life cycles image - Cysticercus form of juvenile tapeworm cyst.

Taenia tapeworm life cycles diagram - Strobilocercus form of juvenile tapeworm cyst. This strobilocercus has been drawn 'evaginated' (with its head and neck poking outside of the fluid-filled bladder structure). Typically

this evagination only occurs once the strobilocercus is eaten by a definitive host animal (the cystic 'bladder'

then digests away, leaving the head and neck behind to attach to the definitive host's intestinal wall). When it is located within the tissues of the intermediate host, the strobilocercus is generally 'invaginated'

with its head and neck hidden within the fluid-filled cystic bladder structure. Thus it really should have been drawn more

like the cysticercus (picture 1), just with a longer neck region.

Taenia tapeworm life cycles picture - Coenurus form of juvenile tapeworm cyst.

Side note - the cysticercus form of Taenia crassiceps is capable of budding. A single

cysticercus of this species can bud off replicas of itself, each containing an infective scolice. This increases the amount of regional tissue damage caused by the tapeworm larvae and results

in the formation of several adult tapeworms within the definitive host, should the definitive host happen to

consume all of the cysts in the budded cluster. The condition can mimic hydatid disease, but should

be differentiated from this, much nastier, condition.

The Taenia cyst can cause damage to the intermediate host animal's tissues as it grows.

The damage is generally in the form of pressure atrophy - the cyst crushes the tissue cells around it as it expands

in size, causing the cells of the infested organ to die off bit by bit. Sometimes the cyst

crushes a vital blood supply, killing the cells and organs supplied by that circulatory pathway. Sometimes

the cyst crushes other vital tubular structures like the gall bladder, ureter, bile duct

and bronchi, causing severe dysfunction of these conduits. Sometimes the cyst can leak small amounts

of fluid into the surrounding tissues, resulting in severe allergic reactions (the host immune

system attacking the fluid) and painful tissue inflammation of the area. Such aggressive inflammation (e.g. immune cells releasing chemicals that destroy and damage protein and cell structures) can

badly injure the surrounding host tissues, even though the main aim of the attack was to destroy the foreign cyst-fluid and 'save' the host tissues. Should a large

cyst happen to rupture, the massive fluid release can result in a severe anaphylactic reaction

(the sudden death of the patient is quite possible should this occur).

The symptoms and consequences of this damage depends very much on the size and number of the Taeniid cysts

present and on the organ location that the cysts have invaded. Because most organs

(not the brain) have a high degree of tissue redundancy (meaning that a lot of tissue can be lost before

symptoms of organ damage present), a quite-sizeable population of small Taenia cysts may not produce any obvious symptoms in the intermediate host for a long time. The liver is a good example of this - many small Taenia cysts in the liver may not cause any signs of ill-health

(unless they happen to be positioned such that they squash a vital liver structure like the gall bladder

or common biliary duct). Lung cysts may also present initially with minimal signs,

however, the animal will generally develop coughing, shortness of breath, pneumonias and wheezing

as the cyst/s expand. On the flip side, certain other organs can not tolerate even the smallest of tapeworm cysts

without showing side effects. The brain is a classic example of this - even a very small cyst in the brain

can result in severe neurological deficits within the infested host. This is why Taenia solium

and Taenia multiceps (both of whom love to invade the brain) can be so dangerous to their intermediate

host animals.

Images of Taenia cysts in organs:

http://www.cfsph.iastate.edu/DiseaseInfo/ImageDB/TAE/TAE_001.jpg - Taenia solium cysts in pig muscle (pork).

http://images.medscape.com/pi/features/slideshow-slide/neurocysticercosis/fig1.jpg - Taenia solium cysts in a human brain.

http://cal.vet.upenn.edu/projects/paraav/images/lab7-16.jpg - hundreds of Taenia saginata cysts in a cow heart.

http://www.aans.org/bulletin/images/Vol17_3_08/OcularCysticercosis_small.jpg - Taenia solium cyst in a human eye.

The Definitive Host Becomes Infested With Adult Taenia By Consuming the Intermediate Host:

The definitive host animal (dog, cat, human) becomes infested with the adult tapeworm form of the Taenia tapeworm life cycle by consuming the larval-cyst-infested organs of an intermediate host animal that has become infested with the 'right' Taenia species for that

definitive host animal. This host-specificity is quite important. The right Taenia species must be ingested

by the right host if an adult tapeworm is to result. A cow infested with Taenia saginata cysts

could be eaten by a dog or a cat without either of those two animals getting the adult tapeworm.

This is because the adult T. saginata tapeworm only develops in the intestines of a human being. In the dog or cat, the T. saginata tapeworm cyst will simply be digested and not turn into an adult worm.

Likewise, a human who ingests the undercooked meat of a sheep will not get Taenia ovis

because Taenia ovis requires a canine host to achieve adulthood. And so on.

The definitive host animal must eat an infective, fertile cyst, containing active

protoscolices, if it is to become infested with the adult Taeniid tapeworm forms.

This sort of consumption is common in the animal world, where cats and dogs, both wild and domestic, feast on the fresh, warm offal of their freshly killed prey (e.g. rabbits, rats, mice, voles, sheep). It can also occur in the domestic domain, when farmers offer the raw innards or body parts of freshly-killed livestock and rabbits to their dogs and cats or hunters allow their pets to snack on the results of their shooting trips (e.g. pig and deer hunters often feed their dogs on the raw meat and organs of the animals that they have killed). In the kitchen, it is man

who is at risk of becoming infested. The consumption of undercooked meat, particularly pork and beef, can result in the human diner gaining an unwanted parasitic guest.

When the definitive host animal consumes the tapeworm-cyst-infested intermediate host tissues, the mini-tapeworm

protoscolices (which up until now have been 'invaginated' - held inverted inside of their cystic bladder support structures) evaginate and poke out of their bladder support structures. The supportive bladder-like structures

digest away and only the head and neck of the protoscolice is left, floating freely within the small intestinal

tract of the definitive host carnivore. These protoscolices will develop into final-stage adult tapeworms. They will attach

to the wall of the host's intestinal tract and begin feeding and budding off proglottid segments. Eventually mature proglottids will develop, be fertilised and become egg-laden. Egg-containing proglottids will eventually start shedding out into the droppings.

The first adult tapeworm eggs will start appearing in the definitive host animal's environment about 6-8 weeks after the Taenia-cyst-infested intermediate host animal was first ingested. Adult worms

can live in the definitive host animal for a period of 6 months to almost 3 years, but some species are known (e.g.

T. saginata of man) whose adults can live for around 20 years in a single host.

Thus the Taenia tapeworm life cycles continue ...

Author's note: The Taenia tapeworm life cycle tends to be most successful and prevalent

when the 'right' definitive hosts and intermediate hosts for that species of Taenia live and feed in close proximity to one another (which makes obvious sense). Strong tapeworm life cycles tend to establish in environments between animals that have a natural host-prey relationship. For example, a tapeworm life cycle commonly exists in areas where cats and rodents co-exist. The infested cat defecates Taenia taeniaeformis tapeworm eggs onto the grass, infesting the local herbivorous rodent population

with hepatic strobilocercus cysts that are later consumed by the cat when

it hunts and consumes the rodents. Similar problems occur on farms when tapeworm-infested dogs

are allowed to defecate onto the grasslands and pastures of sheep and cattle. These livestock

animals become infested with cysts, which the dog might later get to consume if it comes

across the carcass of an animal that has died as a result of its parasitism.

It is for this reason - the ability to maintain a strong definitive-host and intermediate-host

relationship (essential to tapeworm life cycles) - that the majority of domestic animal

Taeniid infestations occur in dogs and cats that come from or have regular access to rural regions (livestock and rabbits),

grain-stores (mice and rats), farms and wild spaces (e.g. national parks with lots of wild animal intermediate hosts).

Dogs and cats that spend lots of time in these environments, hunting their own prey and feeding on offal and carcasses (e.g. working dogs, herding dogs, hunting dogs, pig-dogs) are at greater risk of carrying and passing on Taeniid tapeworms.

Prevention of tapeworm cysticercosis and coenurosis in sheep and cattle really requires that infected

dogs and canids not be allowed access onto animal pastures. This is often hard to enforce so farmers looking

to prevent their livestock from becoming spoiled by tapeworms should deworm all their dogs regularly, avoid feeding

them raw offal and meat and put up suitable fences to avoid having potentially-infested wild canids pooping

into the pasture.

2) Taenia tapeworm symptoms and outcomes - the significance of Taenia infestations in intermediate and definitive host animals.

The following two sections contain information on the significance of Taenia tapeworm infestations

in both definitive host and intermediate host animal species. I have elected to discuss

the significance of these tapeworm parasites for both types of hosts because, even though this is primarily a

small animal veterinary website, the impact of the parasites on the intermediate

host animals is highly significant (often life-threatening) and an integral reason as to why there is a need for the prevention of tapeworm parasites in the definitive host animals (we do not just prevent tapeworms in dogs and cats for their well-being but for the well-being of livestock animals and other intermediate hosts also, whose very lives could be lost should they contract the tapeworm cysts from the egg-laden feces of infested dogs and cats).

When we talk about tapeworm infestations, most people only picture the adult tapeworm infestation of the intestinal

tract of the definitive host animal or human. What many people fail to realise, however, is

that most adult tapeworm infestations of dogs, cats and people typically produce little discomfort or evidence of disease (unless the worms are large in size; large in number or the host is health-compromised

in some other way) and are of little clinical significance to the carrier (the obvious exception being the nasty Taenia solium pork tapeworm, which poses a dangerous cysticercosis risk to the human carrier if it remains undiagnosed and untreated).

In fact, most of the big disease problems seen with Taenia tapeworm infestations actually occur in the intermediate host animals: the result of internal organ infestation with the

juvenile cystic forms of the tapeworm life cycle. Numerous, expanding cysts in important

bodily organs can be devastating for the intermediate host animal, often resulting in significant symptoms of disease and disability. From an animal production viewpoint, Taenia cysts in the meat and organs of livestock animals (e.g. pork and cattle

in particular) can also be devastating, as such infested meat is often down-graded or outright rejected for sale. In the case of pork, meat infested with Taenia solium cysts

is outright dangerous for the consumer, should unprocessed, raw pork enter the human food chain.

2a) Taeniid tapeworm symptoms and significance in intermediate host animals.

1) Disease significance:

The disease significance of Taenia tapeworms is very much dependent upon the species of

Taenia we are talking about and, in particular, which body tissues the juvenile tapeworm

cysts tend to localise in.

Some types of larval Taenia cyst (e.g. Taenia pisiformis cysticerci of rabbits)

localise within the abdominal spaces of their intermediate host (i.e. in the fat and connective tissues surrounding the abdominal organs), where they have plenty of room to expand and grow without impacting on the organs. In such cases, no symptoms may be appreciated by the infested animal or its owner (if one exists).

Other types of Taenia (e.g. Taenia taeniaeformis, Taenia hydatigena, Taenia solium) have a trophism

for the liver. Being a highly redundant organ (i.e. meaning that lots of tissue can be lost from the liver before symptoms

of liver disease will occur), small numbers of slowly expanding cysts may not produce any

symptoms of hepatic disease in the animal for a long time. In larger numbers and sizes, however, liver dysfunction

can eventuate, resulting in wasting, thinning, jaundice, 'fluid-belly' (ascites) and general unwellness of the animal before death. Alternatively, a small number of cysts located in particularly 'bad' regions of the liver (e.g such that they compress the biliary ducts or major blood vessels) could result in significant

symptoms of disease (e.g. biliary obstruction) even though only a small number of cysts is present

and most of the liver tissue is healthy.

Side note - if a massive number of tapeworm eggs is eaten all at once, the huge influx of embryonic

tapeworms into the animal's liver can cause very severe injury to the liver, resulting in acute

hepatitis and death. At this point, no second-stage larval cysts will yet have formed - it will be the migrating

first-stage larvae (the hexacanths) doing all the damage.

Various other species of Taenia (Taenia solium, Taenia saginata, Taenia ovis, Taenia serialis)

are attracted to the muscles of the intermediate host animal, including the heart muscle. In low to medium numbers, these cysts will usually cause no symptoms in the infested animal, unless they are located within the heart where even small populations can result in sudden death. In large numbers, such cysts

might be expected to cause pain in the affected muscles, something that the owner

might recognise as lameness or stiffness of the gait. It is worth noting that, aside from the disease

significance, the presence of larval cysts in the muscles and meat of affected cattle and pigs

has significant financial ramifications for the affected farm, as such meat is generally rejected

for commercial sale and may pose a serious risk to human health (T. solium).

Taenia multiceps, as an individual Taeniid species, poses a severe health threat to sheep (occasionally humans

and other animals) who contract it because it tends to localise in the brain. Even a single, expanding cyst can produce severe signs of neurological dysfunction (brain damage) and even death in the sheep infested with it. The disease in sheep is nick-named 'gid' because it often makes the sheep wobbly and uncoordinated when it walks (i.e. 'giddy'). Other signs of the condition also include: paralysis, head-pressing, star-gazing, circling, seizures and death. It is a terrible condition for the sheep intermediate host, yet

the dog definitive host will tend to show little sign of infestation itself. Taenia solium is

similarly dangerous because it will also often invade the brain of the intermediate host that it infests (pig, human).

Some species of Taenia (e.g. Taenia solium) are less selective about where

their cysts localise, making them extremely dangerous for the animal (pig or human)

that contracts them. They produce major disease concerns when their expanding, space-occupying cysticercus

larval cysts turn up in the vital organs (e.g. brain, liver, lung, kidney, eye) of intermediate host animals (pigs) and, most worryingly, people. The cysts grow and expand, crowding out and compressing the cells that

make up the organs they have invaded. This eventually leads to the dysfunction of these internal organs

as vital structures get compressed (e.g. blood vessels that supply nutrients and life to organs may be closed off; drainage structures like biliary ducts and ureters, which help to draw fluid from various organs, may be compressed

shut; airways that provide oxygen to the lungs may become squashed by the enlarging cysts and so on) and even destroyed (e.g. compression of organ cells by an expanding cystic mass can result in their death from compression injury - termed "pressure atrophy"). If not diagnosed and treated promptly, the cyst-induced organ damage (e.g. brain damage, lung damage) can become so severe that the animal or

person with the Taeniid disease will become permanently compromised or even die.

Humans with Taenia solium of the brain can show a range of neurological signs including: fever, chronic head-ache, irritability, blindness, dementia, seizures, focal lesions, incoordination, wobbliness, confusion, paralysis and personality changes. Some

people present with signs of stroke and others can present with sudden death.

Allergic and anaphylactic reactions are also possible when large larval cysts are present within the body

of a human or animal. Some larval cysts will leak small amounts

of protein-rich fluid into the surrounding host tissues, resulting in allergic reactions at

the site of the leakage (the host immune system attacking the fluid) and painful tissue inflammation of the area. Low-grade inflammation can present vaguely as signs of fever, rash, night-sweats and increased lymph node size. More aggressive inflammation (e.g. immune cells massively releasing chemicals that are designed to target and destroy protein structures and 'foreign substances') can badly injure the surrounding host tissues, even though the sole aim of the immune attack was just to destroy the foreign cyst and its oozing fluid. Should a large

cyst happen to rupture, the massive fluid release can result in a severe anaphylactic reaction

(the sudden death of the patient is quite possible should this occur).

Another risk posed to all animal intermediate hosts by Taenia, regardless of

species and organ distribution, is septic peritonitis. When Taenia eggs are consumed

by the intermediate host animal, the embryonic tapeworms (hexacanths) need to penetrate through the gut wall of the

animal if they are to enter the internal organs. A penetrating embryo can draw intestinal bacteria

through the gut wall with it, resulting in severe, life-threatening bacterial infection within the abdominal cavity of the animal. Some of these bacteria

(especially Clostridial forms) can be extremely nasty, resulting in septicaemia

and death within hours to days of infection.

It is possible for larval cysts to undergo weird mutations within the tissues of the intermediate host animal. Should the wrong cellular mutations occur, the cysts can start to grow rapidly in bizarre, atypical

ways, aggressively invading the host's tissues and organs and acting like a cancer. Such a mutated,

malignant larval structure of non-host-tissue-origin is termed a teratoma. Surgery to remove the organism

is the only way to save the host (provided the condition is not too advanced) and, in many cases, the surgeon will find it difficult to determine exactly what the teratomatous object in question is, it is

so far removed from its normal, round, cystic appearance.

The risk of immune system compromise and subsequent death from other unrelated disease causes also goes up for animals severely infested with Taenia cysts. Even though the cystic infestations may not be bad enough to cause death

outright (certainly not rapidly, in any case), significant larval cyst burdens can result in the animal's appetite being reduced and its energy expenditure being increased (energy lost through

immune attacks on the cystic 'foreign bodies' and general inflammatory processes) - a situation that results in the overall thinning, ill-thrift and ill-health of the affected animal. Such unwell

animals are liable to having a degree of immune system compromise, meaning they are more prone to dying from common infections and parasites that, before, would not have bothered them.

Animals that show ill-thrift, thinning and general weakness (as per above paragraph) are liable to

being predated upon by domestic and wild animal predators. For example, a thin, skinny, weak

rabbit infested with a large T. serialis burden is more at risk of being eaten by a hawk

or a cat.

2) Commercial significance:

From a livestock production point of view, the financial losses to commercial meat producers can also

be significant. Meat and offal infested with Taenia cysts of any species (even those

species not infective to man) will most likely be rejected from the commercial food chain (i.e. won't be able to be sold) because people won't buy it (people are unlikely to

eat meat or organs with cysts in them).

Should Taenia saginata cysts be found in beef (meat), the meat rejection is likely to be

doubly-enforced since the organism is of significance to human health.

Should Taenia solium cysts crop up in pork, the negative reaction is likely to be even greater. That

the meat in question will be rejected is obvious, however, the consequences for the infected farm may

be even greater than this. Taenia solium is known to be highly dangerous to man and

it is considered exotic and notifiable in many countries. A farm that tests positive to this organism

may well find itself under strict quarantine with an investigation underway as to where the

infection came from (other farms might also become implicated and many livestock may be destroyed

as a result).

Obviously, any deaths that occur as a result of infestation with any of the Taenia species (e.g. Taenia multiceps in the brain of a sheep, Taenia ovis entering the heart)

count as commercial losses. A dead animal produces no meat, wool or milk and is a financial

loss. Should that deceased animal be of genetic value (e.g. a good stud bull, a high-yield dairy cow), then the

commercial loss is compounded through the loss of those 'productive' genes to future generations of animals.

Extra cost will also be incurred in replacing the valuable animal.

Additionally, the overall loss of stock productivity that can occur as a result of even moderate

infestations with Taenia cysts should not be forgotten. Even though cyst infestations may not be enough to cause death

outright (certainly not rapidly, in any case), significant larval cyst burdens can result in the animal's appetite being reduced and its energy expenditure (energy lost through

immune attacks on the cystic 'foreign bodies' and general inflammatory processes) being increased - a situation that results in overall thinning, ill-thrift and ill-health of the affected animal. Such animals are likely to have less meat (meat that might not

be saleable anyway) and reduced outputs of both milk and wool of any quality. All of this represents

a commercial loss.

3) Zoonotic and human health significance:

Taenia saginata (beef tapeworm) is of some zoonotic significance to human beings. Humans

who eat undercooked beef (especially 'blue' or tartare-style raw meat) may ingest larval cysts of this Taenia species. When it grows in the human gut, the adult form of this worm can attain

lengths of many metres - a size that might produce symptoms of nausea and discomfort

(see section 2b on definitive host signs) and weight-loss in the human infected with it.

Taenia solium (pork tapeworm) is of huge zoonotic significance to human beings.

Similar to the situation seen with Taenia saginata, humans who eat undercooked pork may ingest larval cysts of this Taenia species. When it grows in the human gut, the adult form of this worm can attain

a good size - potentially producing symptoms of nausea and discomfort

(see section 2b on definitive host signs) and weight-loss in the human infected with it. Of infinitely

more significance, however, is the fact that a human infested with adult Taenia solium can go on to self-infect his/her internal organs with nasty Taenia solium cysts, through even the slightest lapses in personal hygiene. This can result in the eventual death of the person so-infested.

2b) Taeniid tapeworm symptoms and significance in definitive host animals.

Adult Taenia parasites located in the intestinal tracts of animals and people can pose a variety of problems for pets (dogs and cats) and humans including:

- non-specific intestinal disturbances - tapeworms can produce some non-specific signs of

intestinal discomfort and pain (e.g. colic signs) in animals and humans. Tapeworm afflicted humans often complain of cramping and nausea: signs that are generally difficult to ascribe to animals, but which probably do occur in them also (animals can't actually describe such vague feelings of cramping or nausea to us humans - so we are generally unaware of these signs in them). Vomiting may also result.

- non-specific appetite changes - tapeworms can cause some animals and people

to go off their food or to become fussy or picky about their eating habits (this appetite loss is possibly the result of such factors as abdominal pain and nausea - described above). In contrast, certain other individuals

develop a ravenous appetite in the face of heavy tapeworm infestations because they are competing with

the parasite/s for nutrients (they need to physically eat more to provide enough nutrition for both themselves and the worms).

- non-specific fever - tapeworms can be associated with recurrent fevers.

- body weakness, headaches, dizziness, irritability and delirium - sometimes described in human tapeworm infestations, non-specific signs of weakness, headache and dizziness may occur in animals also. Whether we would ever actually be likely to diagnose these sorts of non-specific signs in our pets is the real question, however - if our pets can not actually describe sensations of dizziness or headache to us humans, then how would we ever know? It certainly is a sign described in human tapeworm conditions, however.

- malnutrition - very large numbers of adult Taenia tapeworms present in the intestinal tracts of dogs and cats (particularly small puppies and kittens) can result in the malabsorption of nutrients (food) by the infested animal. This can cause the tapeworm-parasitised animal to not receive the nutrition it needs (i.e. to not absorb its food properly), resulting in malnourishment, weight loss, ill-thrift and poor growth. It is possible that malnutrition may also occur in humans who have heavy tapeworm

burdens, although this finding would be expected to be less commonly seen in humans than in animals.

- poor coat and hair quality - severe malnutrition and malabsorption of vitamins, minerals and proteins can result in reduced quality of the haircoat - e.g. brittleness, thinning, coarseness and loss of lustre of the coat.

- intestinal irritation and diarrhea - when an adult tapeworm inhabits the small intestine of an animal or human, it finds a suitable site along the lining of the intestinal lumen and grasps on to it using suckers (acetabula) and a spiny anchor-like organ called a rostellum. This spiky tapeworm grip is irritating to the wall of the small intestine, creating discomfort for the host and alterations in intestinal motility

and regional intestinal mucus secretions, which can result in diarrhea (note that diarrhea is mainly seen only in very heavy tapeworm infestations). In some individuals, the penetrating rostellum causes a severe inflammatory, allergic reaction within the host's intestine (the host's immune system actively rejects and attacks the tapeworm proteins), causing the animal host to exhibit abdominal pain and diarrhea. Note that T. saginata, sometimes called the 'unarmed tapeworm', lacks a spiny rostellum so is not quite so damaging to the human intestine.

- intestinal blockage - it is possible for massive tapeworm infestations to block up

the intestines of animals (especially small puppies and kittens) and children, producing signs of intestinal obstruction (e.g. vomiting, shock and even death). This is not common, but it can occur if worm burdens are large and/or if someone deworms the infested animal, killing all of the worms in one hit (the tapeworms all die and let go of their intestinal attachments at the same time, resulting in a vast mass of deceased tapeworms flowing down the intestinal tract all at once and causing blockage).

- intestinal perforation - rarely, some adult Taeniids (e.g. Taenia saginata beef tapeworms) can perforate the intestinal wall, ending up inside of the host's abdominal cavity. This can result in life-threatening abdominal inflammation and infection and septicaemia.

- appendicitis, biliary obstruction, pancreatitis - rarely, some adult Taeniids (e.g. Taenia saginata beef tapeworms) can migrate up into the duct systems of the pancreas and biliary tract (bile duct), producing blockages and painful inflammation of these regions. Some may even enter the appendix and cecum, causing nasty inflammation of these regions (termed appendicitis and typhlitis respectively). This can result in life-threatening complications that may require surgical correction.

- perineal or anal irritation and scooting - the migration of tapeworm segments from the anuses of infested dogs and cats can result in itching and irritation of the anus. The dog or cat

will respond by excessively licking the anus in order to remove the irritation or, if it can not reach, it will drag and rub its bottom on the ground to remove the irritation. This bottom rubbing, called "scooting", is usually a sign of anal or perineal irritation and evacuating tapeworms can be one cause of this (side note - anal gland impaction or infection is a much more common cause of scooting, however, it can be a sign seen in 'wormy' animals). Note that anal irritation can

be experienced by people infested with tapeworms, resulting in 'bottom scratching' (typically pin worms cause most

cases of anal irritation in people, not tapeworms).

- annoyance - most pet owners don't like to see or hear their pets fastidiously licking their bottoms or rubbing their butts along the carpet. This annoyance is compounded when the rubbing activities result in fecal staining of floors or if tapeworm segments are actually seen extruding

from the animal's anus;

- gross-out factor - the sight of long tapeworms in the feces and/or white,

grub-like tapeworm segments crawling from a pet's anus is revolting and off-putting to many people who see such infestations as a sign of 'dirtiness' and 'disease' (even though clean pets can and do get tapeworms of course). The disgust and horror is likely to be compounded if the tapeworm in question

is actually coming out of you!

- zoonosis (human infestation) - Adult Taenia solium tapeworms produce

eggs that are infective to humans. Humans who inadvertently ingest fecal matter containing tapeworm eggs

can develop life-threatening larval tapeworm infestations of the organs (including the brain) potentially resulting in death.

Of all of the problems mentioned above, the disgust factor (gross-out factor) is probably the most

significant and commonly seen in the vet clinic. Tapeworm-associated problems like malnutrition, intestinal irritation, perineal irritation, diarrhea, intestinal blockage and poor coat quality are seen of course and are greatly problematic for the host animal when they do occur, however, it must be stated that it generally

requires a massive tapeworm burden to be present before such severe signs are likely to be encountered

in practice. As a vet in Australia, I have not personally seen an adult

Taenia tapeworm burden so massive as to result in a major malabsorption or intestinal disturbance issue (although under certain hygiene and living conditions, I do not doubt that it probably occurs). Far more commonly, people come to me in a panic because they have just found a large, white worm in the droppings of their cat or dog or seen a pale, fat, maggot-looking tapeworm segment slither out of the anus of their puppy. In these quite common situations, the animal in question is generally healthy and fine (it just needs worming treatment) - it's the owner who's the one needing the reassurance (and the smelling salts)!

3) Treatment and prevention of Taenia tapeworm infestations in animals.

Adult Taeniid tapeworms in dogs and cats (and people) can be eliminated from the animal's intestines

using tapeworm-specific anti-cestodal medications like praziquantel or niclosamide. Of the

two drugs, praziquantel is the anticestodal drug most commonly included in most commercially-available

dog and cat 'all-wormers' because it has good activity against another nasty tapeworm parasite

called Echinococcus* (the hydatid tapeworm), which niclosamide does not. Detailed information on praziquantel is contained below. Passing mention is made about niclosamide

and other lesser-used anticestodal drugs in the below section marked "Other Anti-Cestodal Drugs."

When an adequate dose of either anti-tapeworm drug is administered to the definitive host animal, the Taeniid tapeworms die and are voided in the host animal's feces (pet owners may find several large, dead tapeworms

in their animal's feces following the administration of just such a wormer). This single treatment is usually curative, however, several doses may be needed to completely rid an animal of a very large tapeworm

burden (if a large tapeworm burden is suspected, the praziquantel can be repeated two-weekly for a couple of doses

to be sure of getting them all).

Author's note: Be aware that most deworming medications (aside from some heartworm meds) do not generally last very long in a treated-animal's system. When an all-wormer is given to a pet, the drugs work rapidly, killing off the adult worm parasites, before disappearing. The drugs do not hang around to protect the pet against subsequent tapeworm infestations. This means that should

the pet continue to eat larval-tapeworm-infested rodents, rabbits and livestock in the days following

the deworming treatment, they will most likely become rapidly re-infested with adult tapeworms.

Following the ingestion of a cyst-infested intermediate host rodent, rabbit or livestock animal, a definitive host

dog or cat can have a reproductively-mature, proglottid-shedding adult tapeworm inside of its

intestine within a mere 6-8 weeks. In high-transmission situations (e.g. a dog fed frequently on raw offal, a

cat that hunts), this could mean that a pet owner might need to repeat worm (tapeworm-treat) his dog or cat every 6-8 weeks to keep the adult tapeworm numbers under control!

Because such frequent 6 weekly worming may not be practical for some pet owners (particularly owners

of hard-to-pill cats), the best option for the ongoing control of Taenia tapeworms is to:

a) give the animal regular tapeworming medications (as per the manufacturer's directions) and

b) not allow the animal access to foods likely to contain larval tapeworms (e.g. raw carcasses, raw offal, hunting).

* be aware that not all tapeworm-killing drugs kill the

nasty Echinococcus hydatid tapeworm species, so do make sure you check that any tapeworm medication you give is appropriate for killing this particular tapeworm species. Hydatid tapeworms are not Taenia species and so do not really belong on this page, however, they are so dangerous that I do not want them to be forgotten during the discussions on Taenia treatment and prevention. (Praziquantel

is a good choice for hydatid tapeworms and is easy to get. For other anti-tapeworm medication options,

see the notes at the bottom of this section to see whether or not they kill Taenia and Echinococcus.)

Praziquantel.

Praziquantel is a powerful tapeworm-killing drug that is generally included in the vast majority

of commercially-available 'all-wormers' given to dogs and cats. It has a high margin of safety in dogs and cats

(and many other species) and exhibits very good activity against most of the major tapeworm species affecting our domestic pets (including: the common flea tapeworm - Dipylidium caninum; the hydatid

tapeworms - Echinococcus granulosus and E. multilocularis; the zipper worm - Spirometra

and the many varieties of Taenia tapeworm species). It is because of this excellent activity against such a wide range of pet tapeworm parasites that praziquantel tends to be favored over

niclosamide and most other drugs in the control of tapeworms in domestic household animals.

How it works:

Tapeworms are coated in protein molecules that shield them from being recognized and attacked by

the host animal's immune system. These protein molecules turn over and shed from the tapeworm's body surface (tegument)

constantly. By the time the host's immune system recognises and starts to attack one lot of tapeworm surface molecules, these have been shed from the tapeworm's 'skin' (tegument), leaving the immune system with nothing recognisable to attack.

Praziquantel works by disrupting the surface tegument of the tapeworm such that the animal's immune system is capable of recognizing the tape worm as foreign and actively attacking it. Additionally, praziquantel

also works by massively increasing the influx of calcium ions into the tapeworm's body. This calcium overload causes

the worm's muscles to become over-stimulated such that the worm develops stiffness and rigidity. The rigid

tapeworm is unable to maintain its hold on the host's gut wall and is, consequently, voided from the animal's intestinal tract via the faeces.

Features of praziquantel:

- The treatment of choice for adult tapeworms in dogs and cats. Can be used in people (do NOT be tempted to self-medicate with your pet's medications though - see a doctor if you require a tapeworm treatment).

- Kills a wide range of adult cestode (tapeworm) species in definitive host people and animals.

- Also kills some forms of trematode (fluke) parasite in livestock animals.

- In very high doses, praziquantel also kills certain intermediate-stage, larval tapeworm forms (including

cystic larval forms of Taenia like T. solium). For example, praziquantel and albendazole were used together

to treat a woman infested with the budding cysticerci of Taenia crassiceps (ref 9) to good effect.

- Very effective at killing adult Dipylidium caninum flea tapeworms, adult Taenia tapeworms, adult hydatid tapeworms and also many other important tapeworm types afflicting domestic animals.

- A dose of only 2mg/kg is needed to kill all adult Taenia types (some Taeniids only need 1mg/kg). Most all-wormers actually contain a dose of 5mg/kg praziquantel (a higher dose - needed for other tapeworm species), which is more than ample for killing this adult tapeworm Genus.

- A dose of 2.5-5mg/kg is needed to kill Dipylidium. Most all-wormers contain 5mg/kg praziquantel, which is ample for killing this flea tapeworm.

- A dose of 5-10mg/kg is needed to kill hydatid tapeworms (Echinococcus species) in dogs. The higher

dose range is recommended to kill sub-adult forms of the worms in dogs. Most all-wormers contain 5mg/kg praziquantel, which is within the dose range for killing these nasty tapeworms, however, given how dangerous hydatid tapeworm infestations are to people, if I was a dog owner living in a high hydatid risk situation, I would probably err on the side of caution and give the higher dose (10mg/kg). For info on hydatid tapeworms, see our hydatid tapeworm page.

- Some tapeworms like Spirometra mansoides and Diphyllobothrium erinacei require an intermediate, high dose range (7.5mg/kg) be given on 2 consecutive days to clear them.

- Many of the tapeworms and flukes afflicting livestock animals need high doses of praziquantel if they are to be cleared (in the order of 15-30mg/kg and higher).

- Praziquantel, given orally, absorbs into the animal's body rapidly, reaching many organs including the liver and brain (this body-wide, systemic absorption is why praziquantel is effective against Schistosoma and certain larval tapeworm forms).

- Praziquantel has a wide safety margin and is difficult to overdose (dogs were tested on up to 180mg/kg orally with little side effect).

- Praziquantel is thought to be safe in pregnant and breeding animals (check with your vet to be sure though).

- Some praziquantel-containing products advise not using praziquantel in puppies or kittens under 4 weeks of age. Given

that pups and kittens 3 weeks and below are only fed on milk, they do not really need a tapewormer anyway as tapeworms are

only caught by eating intermediate host tissues.

- Second to niclosamide, praziquantel is a good option for treating Taenia saginata in people. It is often given to human patients in conjunction with niclosamide.

- A major choice for treating adult Taenia solium in people.

- Side note - Praziquantel also kills Schistosoma - an important parasite of humans, which causes a terrible, often fatal, liver condition called bilharzia (common in third world countries).

- Side note - Does not kill roundworms or hookworms or other nematode parasites. Praziquantel kills cestodes (tapeworms) and certain trematodes (flukes) only.

Author's note: A related product called epsiprantel has been used to kill flea tapeworms and

Taenia

in dogs and cats. I have never used the product personally and can not vouch for its efficacy or safety.

NOTE - Please read our disclaimer before attempting to self-diagnose and dose your animals with

any drugs mentioned on these pages. Pet Informed is a general advice website only and mistakes can be

made - we always recommend that you double-check any of our information with your own vet.

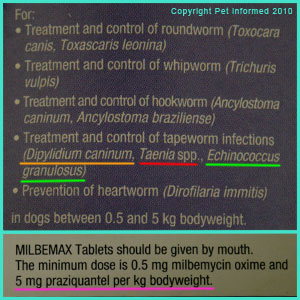

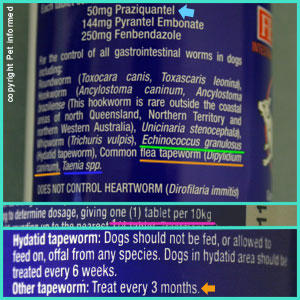

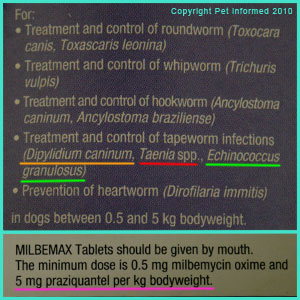

Taenia tapeworm life cycle picture: These are photographs of the box-labels of a common dog and cat

all-wormer called Milbemax. You can see from the first image that the product contains praziquantel

(25mg of praziquantel per tablet - underlined in aqua). The second image shows the range of parasites that

the product kills. The flea tapeworm, Dipylidium caninum (underlined in orange), hydatid tapeworm (underlined in grass green)

and Taenia tapeworm (underlined in red) are all listed as parasites that this product kills. Also mentioned on the Milbemax box was the minimum recommended dose rate of praziquantel (underlined in pink) - it is listed as 5mg/kg.

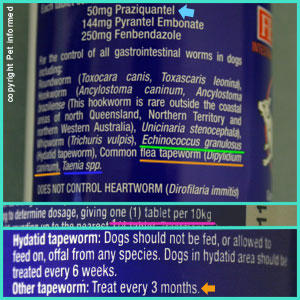

Taenia tapeworm life cycle picture: These are photographs of the bottle-labels of a common dog and cat

all-wormer called Fenpral. The first image is a picture of the product bottle (dog version of Fenpral). The second image shows that the product contains 50mg of praziquantel per tablet (blue arrow). The image shows the range of parasites that

the product kills. The flea tapeworm, Dipylidium caninum (underlined in orange), hydatid tapeworm (underlined in grass green)

and Taenia tapeworm (underlined in blue) are all listed as parasites that this product kills. Also mentioned on the Fenpral bottle is the minimum recommended dose rate of praziquantel (underlined in pink) - it is listed as being 1 tablet per 10kg of

bodyweight. Given that a single tablet contains 50mg of praziquantel, this must mean that the

minimum dose rate for praziquantel is, again, 5mg/kg (i.e. a 10kg dog gets 50mg so a 1kg dog must get 5mg).

Other Anti-Cestodal Drugs.

Aside from praziquantel, there are other anti-cestodal drugs out there that have some activity against many of the parasitic tapeworms, including Taenia, infesting dogs and cats. I will not make huge mention of them, aside from the basic points below, because many of them are going out of fashion, many are hard to get, most have only a very narrow range of tapeworm activity, many don't

kill hydatids and some have significantly toxic side effects when used in domestic animals. I would not recommend using any of the

below-mentioned drugs to treat hydatid tapeworms in domestic pets (especially dogs and cats) if you have access to

praziquantel (see your vet). Praziquantel is the best as far as I can tell.

Niclosamide:

Prevents the tapeworm from making energy (ATP) from glucose (thus it dies).

Has been used against adult intestinal tapeworms in dogs and cats and people.

Good activity against Taenia. Variable activity against Dipylidium and unreliable against

Echinococcus (not reliable for breaking the hydatid tapeworm life cycle). Not satisfactory for

Echinococcus prevention (therefore not an ideal drug to use in dogs).

Often a first choice in the treatment of Taenia saginata in people. Can be used alone or concurrently

with praziquantel.

Minimal absorption from the intestinal tract and therefore toxicity is low (when used orally).

Must be given on an empty stomach.

Thought to be safe in pregnant or debilitated animals.

Toxic to fish and waterways.

Bunamidine hydrochloride:

Has been used on tapeworms in dogs and cats.

Good activity against Taenia. Fair to good activity against Echinococcus, but variable activity against

Dipylidium (not reliable for breaking the flea tapeworm life cycle).

Must be given on an empty stomach.

Has been known to have significant toxic side effects, including the death of pets.

Dichlorophene:

Has been used on tapeworms in dogs and cats.

Good activity against Taenia. Fair to good activity against Dipylidium, but unreliable against

Echinococcus (not reliable for breaking the hydatid tapeworm life cycle).

Minimal absorption from the intestinal tract, so toxicity is thought to be low (when used orally).

Hexachlorophene:

Mainly used to kill tapeworms and flukes in livestock animals, not domestic pets.

Good activity against Taenia and Echinococcus.

Tests on dogs have found that this drug can have significant toxic side effects in this species (cats unknown but probably of similar risk).

Toxicity concerns make it unfavourable for tapeworm control when better drugs are available.

Bithionol:

Has been used on tapeworms in dogs and cats and many other animal species.

Good activity against Taenia, but variable to low activity against

Dipylidium (not reliable for breaking the flea tapeworm life cycle).

Has been known to have toxic side effects in domestic pets (vomiting, diarrhea), but for the most part is

well-tolerated by dogs and cats.

Nitroscanate:

Apparently effective at killing hydatid tapeworms in dogs.

I can not vouch for its safety.

Epsiprantel:

Effective on Taenia.

Apparently effective at killing hydatid tapeworms in dogs (7.5mg/kg).

I can not vouch for its safety.

Benzimidazole drugs (Mebendazole, Fenbendazole and so on):

Many types of benzimidazole drugs have been studied in order to assess their effects against tapeworms in dogs and cats.

Most of them show good activity against Taenia and some even show good activity against Echinococcus, but none of them

is any good for treating Dipylidium (i.e. not reliable for breaking the flea tapeworm life cycle).

Benzimidazoles have been known to have significant toxic side effects in dogs and cats and other species.

Benzimidazoles are sometimes used to sterilise hydatid cysts in intermediate host animals prior to their surgical removal.

Albendazole has been used to kill Taenia solium and hydatid cysts in people prior to their surgical removal or in cases where such surgical removal is impossible.

Praziquantel and albendazole together were used to treat a woman infested with cysticerci of Taenia crassiceps (ref 9) to good effect.

Mebendazole orally has been used to treat Taenia saginata infestations in people.

NOTE - Please read our disclaimer before attempting to self-diagnose and dose your animals with

any drugs mentioned on these pages. Pet Informed is a general advice website only and mistakes can be

made - we always recommend that you double-check any of our information with your own vet. Again, if you have

access to praziquantel (and all vets usually do), I would use this drug over any of the other tapeworm-killing drugs

mentioned here.

4) Some basics on human Taenia saginata, Taenia solium

and atypical Taeniid tapeworm infestations and the prevention of tapeworm disease (especially pork tapeworm cysticercosis) in people.

Most of this information on Taenia solium pork tapeworm and Taenia saginata beef tapeworm has already been discussed in great detail in sections 1 and 2 of this Taenia tapeworm life cycle webpage. This section (section 4) just summarises it in one block for

those of you who are specifically interested in human tapeworm infestations. If you haven't read sections 1 and 2 of this page, I recommend that you take a look as these sections contain

detailed info on how the Taenia life cycle actually works, how Taenia tapeworms are contracted and

what side effects and disease effects can occur as a result of Taenia infestations. The final

part of this section (4c) describes atypical infestations of humans with other species of Taeniid - a topic which has not been covered previously in this webpage.

4a) Tapeworms in Humans 1 - Taenia saginata beef tapeworm:

Taenia saginata is a very long (3-25 meters in length) tapeworm parasite, whose adult form

is found attached to the small intestinal tracts of human beings. In man it has been known to live for around

20 years within a single individual.

In low to medium numbers, these tapeworms cause minimal side effects in their human hosts (see section

2b on symptoms seen in definitive host animals). Many people might not ever be aware that they have a tapeworm

dwelling inside of them, they can be that benign. At best, their presence (particularly if they are large in size)

might be enough to cause intestinal cramping, mild nausea and appetite fluctuations (often

blamed on other causes) and when their segments (proglottids) start to shed out into the feces, this process

might be associated with anal pruritis (irritation and itchiness of the anus). More than likely, most