Veterinary Advice Online - Bird Sexing (General Tips on Avian Sexing and Bird Gender Determination).

Many owners of birds (particularly poultry and parrot species) find it very difficult to determine the gender or sex of their avian pets and often need their veterinarian or their local bird-breeder to sex their birds for them.

Many owners of birds (particularly poultry and parrot species) find it very difficult to determine the gender or sex of their avian pets and often need their veterinarian or their local bird-breeder to sex their birds for them.

The fact of the matter is, sexing birds is often quite tricky, even for many veterinarians. Most species of birds lack external sexual genitalia (e.g. a penis or testicles) that can provide an obvious answer as to their sex and many bird species exist whereby the male and female look almost identical in appearance, making gender determination very difficult. Moreover, some common breeds of birds (e.g. budgerigars, cockatiels) have become so in-bred and over-bred and mutated, with regard to their beak or feather colourations and plumage patterns, that, where colour and patterning might once have been a good indicator of sex in these breeds, this is no longer always the case.

This bird sexing page contains some general principles and concepts on how to go about sexing birds yourself (avian gender determination). Information on the bird sexing services your vet can offer you is also included, should the sex of your feathered friend remain elusive. The " how to sex birds" information provided on this page is supported by a number of helpful pictures and links to useful bird sexing sites that may help you to distinguish the boys from the girls.

Bird sexing topics are covered in the following order:

1. Some basic tips when handling and sexing birds for the first time.

2. Sexing birds by their appearance and behaviour - sexual dimorphism between male and female birds of the same species:

2a) Overall body-size differences between male and female birds.

2b) Specific structural size differences between male and female birds.

2c) Colour differences between male and female birds.

2d) Only female birds lay eggs.

2e) Behavioural differences between male and female birds.

2f) Vent-sexing in avian species that have a phallus (penis) - Anseriformes (ducks, geese, swans, screamers), Galliformes (mallee fowls, quails, pheasants, turkeys, peafowls) and ratites (emus, cassowaries, ostriches, rheas, kiwis).

3. Feather sexing chickens.

4. Bird sexing services your vet can provide:

4a) DNA bird sexing (avian DNA sexing): bird DNA feather sexing, blood DNA sexing and eggshell DNA sexing.

4b) Endoscopic bird sexing - what it is and the advantages and disadvantages.

5. Good links (includes links to genetics company sites that provide DNA sexing).

1. Some basic tips when handling and sexing birds for the first time.

There is not too much that can go wrong when attempting to determine the sex or gender of a bird, so long as you are gentle, however, I will draw your attention to a couple of important bird handling points, which should be taken into consideration.

MOST IMPORTANT - before handling any bird for any examination, do your research first:

.

Before you handle and assess the sex of any bird, read up about the species you are dealing with first. Knowing what you are looking for beforehand, gender-wise and age-wise, will help you to determine the bird's sex more quickly, resulting in minimal handling and stress for the animal concerned. Also, some species of birds pose certain risks to the handler during handling, which are useful to know before you attempt to grab hold of the animal.

Before you handle and assess the sex of any bird, read up about the species you are dealing with first. Knowing what you are looking for beforehand, gender-wise and age-wise, will help you to determine the bird's sex more quickly, resulting in minimal handling and stress for the animal concerned. Also, some species of birds pose certain risks to the handler during handling, which are useful to know before you attempt to grab hold of the animal.

Examples of some of the risks posed to handlers by certain avian species:

- Darters and fish-spearing water birds (long necks and sharp, pointed beaks) - highly dangerous species that can and will spear you in the eyes with their beaks if you do not take steps to control their heads and necks properly.

- Raptors (owls, hawks, eagles) - the hooked beaks and claws of these predatory hunting species are very sharp and strong and can cause severe injury if they latch on to someone's skin. Only experienced raptor handlers should handle such species for sexing purposes.

- Large, flightless ratite bird species (emus, ostriches, cassowaries) - this group includes a number of highly dangerous species that can disembowel a man with a single kick. Only experienced ratite handlers should attempt to handle these animals.

- Waterfowl (ducks, geese, swans) - not too dangerous, but they will projectile-poop foul, watery droppings all over you during handling.

- Parrots (e.g. cockatoos, macaws, galahs and so on) - their beaks are very sharp and strong and they have a vicious bite. It is possible for some of the larger-beaked parrots (e.g. cockatoos, macaws) to bite off a person's finger.

- Honey eaters and wattlebirds - these species have an extra-long, spiny back claw that will pierce deeply and painfully into a person's flesh, should the bird manage to grasp hold of a person's finger with their foot.

- All bird species - birds can spread nasty respiratory and fecal-borne organisms (viruses, bacteria, parasites, fungi) to humans through exposure to their feces, dander and respiratory secretions. It is advised that all bird handlers wear surgical masks, eye shields and gloves when handling such animals (particularly wild or aviary-kept individuals).

Some general bird sexing and handling pointers:

- If you can sex the bird without handling it, this is always preferable. Birds do get very stressed from handling and if this can be avoided, it is better for the bird's health. Some of the sexes look so vastly different from one another that handling is not necessary (e.g. Eclectus parrots - see image on right).

- Handle pet birds very gently and quietly, for as short a period of time as possible. Birds are easily stressed and some species (e.g. canaries, finches) can drop dead from fear and heat exhaustion if handled roughly or for excessive periods of time.

- Be aware of the role that age and puberty plays in the development of avian color and plumage sex characteristics. Some species of birds are not able to be sexed as juveniles by their outward feather-appearance and body coloration

characteristics (i.e. they are too young to have developed their mature sex characteristics). Very young birds may need DNA sexing to determine their gender. An example of this - when attempting to sex budgerigars by their cere colour (the colour of the nostril band at the top of the beak), you need to wait until they are sexually mature (over 12 months old). The cere colour is not helpful for determining gender in juvenile budgies.

- If attempting to sex tame birds (parrots and so on), the birds can often be examined while perched upon your hand. Tame birds do not necessarily need to be grabbed and man-handled.

- If firmer handling and restraint is needed (e.g. to pluck feathers from the bird for DNA bird sexing, also known as DNA feather sexing), you should grasp your bird gently, but firmly around the body (wings included). NEVER squeeze birds too hard because this can suffocate them (all birds need to lift their sternums outwards to breathe). If possible, hold the bird in an upright position (in their normal perching position) because birds may find it hard to breath if they are held upside down or pinned down on their backs.

- Be careful. Nervous birds do peck and bite hard!

- It does help to have one person hold the bird, controlling the wings and head, whilst a second person performs the sexing examination. This reduces the chances of the bird getting away and it also reduces the chances of the bird biting or scratching one of the handlers.

- Exceptionally tricky or savage birds (e.g. parrots) can be wrapped in a towel (loosely wrap the upper, bitey half of the bird in the towel, leaving the body and legs free), enabling you to handle the body, wings and genital-region

without getting bitten. Extra care should be taken if the bird also uses its feet as a weapon (e.g. raptors, magpies, wattlebirds) and someone will need to keep these under control.

- Feather plucking (for avian DNA sexing) can be painful and stressful for birds, particularly if

many large feathers are required. This stress and pain can be reduced by performing the plucking procedure

under a very quick, relatively-safe, gaseous anaesthetic. Your vet can provide this service for you.

- Although this might seem a tad obvious, always perform bird sexing or any other bird examination indoors. This way, the bird will not be able to escape into the dangerous outdoors environment if it should manage to wriggle out of your hands. Be sure to choose an indoors environment that is also safe

for the bird, should it escape you. I have seen many horribly burnt feet that were the result of parakeets and cockatiels fluttering down onto oven hotplates! I have also seen broken necks and fractured skulls as a result of birds

flying into glass windows.

- Although this might also seem a tad obvious, if the bird has had its wings clipped you should

perform the bird sexing procedure (or any other avian examination) on the floor or on a low table

(e.g. a short coffee table). This way, if the bird gets away, no injury will occur from the animal falling from a great height.

- Try not to handle extremely newborn birds if you can avoid it. Mother birds (especially new mothers) can become uncertain of their newborn chicks if you handle them too much and get your human smell all over them. This can potentially lead to the mother bird rejecting her babies. Most people like to leave bird

sexing until the baby birds are out of the nest.

- With regard to bird species that can be vent-sexed (see section 2e), do NOT attempt to do this on baby birds, especially newly-hatched birds or day-old chickens. If done incorrectly, vent-sexing can result in the death of newly-hatched birds.

- If you have to handle and sex newborn or unfledged birds, wear disposable gloves (so you don't pass on any diseases to them) and do so in a warm area and for no more than 5 minutes at a time so that they do not get cold and distressed. Chicks should preferably not be taken away from their nest or nesting box. Consider DNA sexing (using the discarded egg shells) of very newborn birds.

- Wear disposable gloves and mask if handling newly-acquired birds whose background (history, breeding, where they came from and so on) is unknown (this includes pet shop and aviary-born birds).

This is particularly important if the bird shows any signs of respiratory illness, sneezing,

nasal discharges, skin sores, feather loss (bald spots), scaly skin or diarrhea or if you already have healthy pet birds back at home. Birds can carry a range of diseases that are contagious to humans and other birds, especially Psittacine species (e.g. mites, coccidia, Hexamita, Giardia, Psittacosis, BFDV - avian beak and feather disease virus - and so on), and wearing gloves and a surgical mask when handling will help to reduce disease transmission.

2. Sexing birds by their appearance and behaviour - sexual dimorphism between male and female birds of the same species.

Sexual dimorphism

2. Sexing birds by their appearance and behaviour - sexual dimorphism between male and female birds of the same species.

Sexual dimorphism is a term commonly associated with the sexing of avian species. The term generally refers to the differences in physical size and/or external appearance (e.g. feather coloration, plumage features, plumage patterns, beak shape, eye color, tail length, the appearance of such adnexal structures as shields, wattles, combs, crests and leg-spurs and a whole raft of other external characteristics) that exist between male and female birds of the same species. A bird species is said to be sexually dimorphic when males and females of the species can be easily told apart by their external appearance. If a species is said to be not sexually dimorphic, this means that the male and female of the species look identical and can not be told apart through their physical appearance.

Some bird species also exhibit a degree of sexual dimorphism with regard to their behavioral characteristics. Obvious behavioural differences may exist between the sexes with such things as: nest-building, egg sitting, chick raising, preening and communal grooming, food gathering, territory guarding, territorial singing, other forms of vocalisation and mating displays (e.g. dancing, sex attraction exhibitions). Knowing which of the sexes commonly exhibits each behavior can provide a clue as to the sex of the bird in question.

2a) Overall body-size differences between male and female birds.

Size differences often exist between the sexes of birds of the same species. Depending on the bird species, sometimes the male is the larger bird and sometimes the female is the larger bird in a pair. Contrary to common belief, the male bird is not always the larger bird in a pair.

Examples of species where the male is the larger bird:

- Wandering Albatross (Diomedea exulans) and most other albatross (Diomedea) species

- Giant-Petrel species (Macronectes)

- Little Penguin (Eudyptula minor)

- Rockhopper Penguin, Erect-Crested Penguin, Fiordland Penguin (Eudyptes species)

- Australasian Grebe (Tachybaptus novaehollandiae)

- Hoary-headed Grebe (Poliocephalus poliocephalus)

- Black-faced Shag (Leucocarbo fuscescens)

- Cormorant species (Phalacrocorax species)

- Australian Pelican (Pelecanus conspicillatus)

- White-faced Heron (Ardea novaehollandiae)

- Rufous Night Heron (Nycticorax caledonicus)

- Australasian Bittern (Botaurus poiciloptilus)

- Cape Barren Goose (Cereopsis novaehollandiae)

- Musk Duck (Biziura lobata)

- Common Peafowl or Peacock (Pavo cristatus)

- Purple Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio)

- Kori Bustard (Ardeotis kori)

- Sharp-tailed Sandpiper (Calidris acuminata)

- Ruff (Philomachus pugnax)

- Kelp Gull (Larus dominicanus)

- Crimson Rosella (Platycercus elegans)

- Green Rosella (Platycercus caledonicus)

- Powerful Owl (Ninox strenua)

- Rufous Owl (Ninox rufa)

- Tawny Frogmouth (Podargus strigoides)

- Superb Lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae)

- Scrub-birds (Atrichornis species)

- Yellow Wagtail (Motacilla flava)

- White's Thrush (Zoothera dauma)

- Western Whipbird (Psophodes nigrogularis) and Whipbirds (Psophodes)

- Superb Fairy-wren (Malurus cyaneus)

- Hylacola species (Sericornis species)

- Friarbird species (Philemon species)

- Miner species (Manorina species)

- Certain Meliphaga honeyeater species

- Certain Lichenostomus honeyeater species

- New Holland Honeyeater (Phylidonyris novaehollandiae) and other Phylidonyris honeyeater species

- Satin Bowerbird (Ptilonorhynchus violaceus)

- Tooth-billed Catbird (Ailuroedus dentirostris)

- Paradise Riflebird (Ptiloris paradiseus)

Examples of species where the female is the larger bird:

- Emu (Dromaius novaehollandiae)

- Cassowary (Casuarius casuarius)

- Great Frigatebird (Fregata minor)

- Least Frigatebird (Fregata ariel)

- Letter-winged Kite (Elanus scriptus) and most other Kite species (Elanus, Milvus, Lophoictinia).

- Black-breasted Buzzard (Hamirostra melanosternon)

- Grey Goshawk (Accipiter novaehollandiae)

- Little Eagle (Heiraaetus morphnoides)

- Spotted Harrier (Circus assimilis)

- Wedge-Tailed Eagle (Aquila audax)

- Falcon species including Australian Hobby (Falco species)

- Button-quail species (Turnix species)

- Comb-crested Jacana or Lotusbird (Irediparra gallinacea)

- Oystercatchers (Haematopus species)

- Bar-tailed Godwit (Limosa lapponica)

- Southern Skua (Catharacta antarctica)

- Jaeger species (Stercorarius species)

- Boobook owl (Ninox boobook)

- Grass Owl (Tyto capensis)

- Owlet-Nightjar (Aegotheles cristatus)

- Regent Bowerbird (Sericulus chrysocephalus)

Size difference is sometimes the only obvious external feature that exists to differentiate between the two sexes. For example, male and female swans look almost identical, but in a mating swan pair, the female is usually the smaller bird and the male the larger.

Bird sexing image 1:

Bird sexing image 1: Black Swans tend to form pairs that mate for life. In a breeding pair, the male swan will normally be the bigger animal of the two. The male swan will also generally have a disproportionately longer neck than that of the female swan. In this picture, there are two pairs of swans. The pair on the right are easy to see. The male swan is most likely the bird on the left in this pair (the larger bird with the significantly longer neck) and the bird on the right is most likely a female.

Bird sexing image 2: Maned ducks (wood ducks or maned geese) tend to form pairs that look after the chicks together. In this breeding pair, the male wood duck is the larger of the two birds (the adult on the left) with the larger, more obvious mane (ridge of dark brown feathers running down the back of the head). The male tends to also have richer, darker, more-sharply-defined feather coloration than the female. The female tends to be lighter brown in color and quite mottled and drab in overall appearance. Basically, the male of the pair wants to be seen to attract mates, whereas the female needs to be more invisible and camouflaged for when she is sitting on eggs.

2b) Specific structural size differences between male and female birds.

2b) Specific structural size differences between male and female birds.

Sometimes the male and female birds of a species are similar in overall size, but show distinct differences in the size, development and/or length of a particular body structural feature. There might be differences in the size or length or development of the bill (beak length), the legs, the neck, the tail feathers, the comb or crest, the flight feathers, the leg spurs, the claws or some other component of the bird's body. This feature might be the only obvious external difference that exists between the two sexes and being able to determine the sex in this way generally requires the sexer to know which specific features of the bird they are to look out for (i.e. having some knowledge of the sexual characteristics of the bird species before starting the examination). It also helps to have several birds in front of you - it is easier to compare the sexes directly if they are in close proximity.

Examples of bird species where the male and female birds differ in beak length or shape:

Examples of bird species where the male and female birds differ in beak length or shape:

- Ibis (Plegadis and Threskiornis species) - males have longer bills.

- Spoonbills (Platalea species) - males have longer bills.

- Grey-crowned Babbler (Pomatostomus temporalis) - male has a longer bill.

- Australasian Grebe (Tachybaptus novaehollandiae) - male has a longer bill.

- Hoary-headed Grebe (Poliocephalus poliocephalus) - male has a longer bill.

- Silver Gull (Larus novaehollandiae) - male has a stouter bill.

- Palm Cockatoo (Probosciger aterrimus) - male has a longer bill.

- Green Rosella (Platycercus caledonicus) - male has a stouter bill.

Examples of bird species where the male and female birds differ in shape or size of facial features (e.g. helmets, facial shields, combs, crests, wattles and lobes):

- Cassowary - the female has a larger helmet.

- Purple Swamphen (Porphyrio porphyrio) - male has a larger frontal shield.

- Eurasian Coot (Fulica atra) - male has a larger frontal shield.

- Frilled Monarch (Arses lorealis) - male has a large white neck ruff, which is small in the female.

- Trumpet Manucode (Manucodia keraudrenii) - male has long feather plumes on the back of the head.

- Maned duck (Chenonetta jubata) - male has a mane of long black feathers running down the back of the head.

- California Quail (Lophortyx californicus) - male has a long black crest extended over the forehead.

- Musk Duck (Biziura lobata) - male has a large pendulous black lobe hanging under the bill.

Sexing swamphens image 3

Sexing swamphens image 3 - The red facial shield of the purple swamphen is present on both male and female birds. It is larger in the male bird.

Sexing maned ducks image 4- The male maned duck (adult duck on the left) has a ridge of long, black feathers running down the back of its head. These feathers make the male duck's head look puffy at the back.

Examples of bird species where the male and female birds differ in talon or claw size:

- Masked owl (Tyto novaehollandiae) - male has smaller talons.

- Leghorn chicken - the male (rooster) has a large spine or 'spur' on the back of each leg.

Examples of bird species where the male and female birds differ in tail length:

- Peacock or Common Peafowl (Pavo cristatus) - male has a long, elaborate tail.

- Rainbow Bee-eater (Merops ornatus) - female has a shorter tail.

- Superb Lyrebird (Menura novaehollandiae) - female has a shorter tail.

- Albert's Lyrebird (Menura alberti) - female has a shorter tail.

- Welcome swallow (Hirundo neoxena) - male has longer tail streamers.

- Barn swallow (Hirundo rustica) - male has longer tail streamers.

- Alexandra's Parrot (Polytelis alexandrae) - female has shorter central tail feathers.

- Spotted Bowerbird (Chlamydera maculata) - female has a longer tail.

- Western Bowerbird (Chlamydera guttata) - female has a longer tail.

Sexing peacocks images 5 and 6 - The male peacock has a long, elaborate tail, which is lacking in the much-drabber female (peahen). The female peafowl (peahen - second image) has a short, brown tail.

2c) Colour differences between male and female birds.

The easiest way to sex birds is when the male and female of a species differ obviously in body coloration. Sometimes the male and female birds of a species are so different in colouration that they can almost look like two completely unrelated species. Examples in the avian world of strong colouration differences that can exist between the sexes include: fairy-wrens (Malurus species), orange chats, painted firetails, gang gang cockatoos, cockatiels, certain species of finches, some species of kingfishers, regent bowerbirds, mangrove golden whistlers, shining flycatchers, peafowls, satin bowerbirds and many kinds of robins. In these situations, sexing individual birds is usually quite easy and rarely requires the bird in question be handled.

Sexing peacocks images 7, 8 and 9 - In no other bird species is obvious color sexual dimorphism as well-known and evident as that of the peafowl. The male (peacock) and female (peahen) are so very different in colouration and appearance that sexing this species is very easy. Image 7 shows a male and female peacock eating side by side. The male is the splendid green bird with the long, luxurious tail and the female is the smaller, brown bird feeding next to him. Image 8 shows a female peafowl (termed a peahen) with her chick. Image 9 shows a young male peacock. His tail is not yet long enough to be worthy of a mate, but his magnificent blue and green and white colouration is already obvious.

Often the color differences that exist between the sexes of an individual avian species are much more subtle. The genders may appear almost identical in colour, with only small variations in the colours or patterns of certain bodyparts available as a guide to help determine the sexes. The sexes might only differ in eye colour (e.g. galahs) or leg colour or cere colour (e.g. budgerigars) or in the colouration of specific feather zones. The sexes might even appear identical in colour except that one of the sexes (often the female) appears generally duller and more washed-out in colouration (less vivid) compared to the other. Subtler still, the sexes could even have identical colouration overall, but differ in such subtle patterning features as: the width of a wing-stripe or body-stripe; the number of dots on the head or another body region; the area of distribution of a colour over a body region and so on. Basically, determining the sex of birds with subtle, miniscule differences in colouration and patterning requires a good knowledge of the bird species (i.e. do your research first and know what features you are looking out for).    Sexing galahs images 10, 11 and 12

Sexing galahs images 10, 11 and 12 - A male and a female adult galah. The adult female galah (middle image) has a red eye. The male galah looks identical to the female, except that his eye is dark brown.

Sexing budgerigars images 13 and 14

Sexing budgerigars images 13 and 14 - A female (image 13) and male (image 14) adult budgerigar. The female budgerigar can not be distinguished from the male on the basis of feather colouration (you can get boys with blue feathers and girls with green feathers, not to mention the whole vast range of other feather colourations that now exist). Male and female budgerigars are generally sexed on the basis of cere colour (the colour of the band of skin at the top of the beak that surrounds the nostrils of the bird). Girl budgerigars have a brown cere and male budgerigars have a blue cere.

For more detail on budgerigar sexing, see our parakeet sexing page.

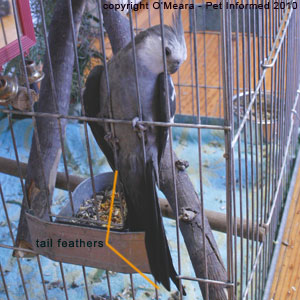

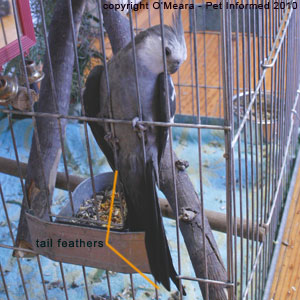

Sexing cockatiel parrots images 15, 16 and 17

Sexing cockatiel parrots images 15, 16 and 17 - This is an image of a female cockatiel. She is not the typical "wild type" colour cockatiel with the red cheek patches, however, we can still tell that she is a female because she has horizontal stripes underneath her tail (tail banding). Image 17 is a close-up of the underside of her tail, showing the yellow and bullet-grey horizontal striping typical of the female cockatiel gender.

Sexing cockatiel parrots images 18 and 19

Sexing cockatiel parrots images 18 and 19 - This is an image of a male cockatiel. He is not the typical "wild type" colour cockatiel with the red cheek patches, however, we can still tell that he is a male because he has no stripes underneath his tail. The male cockatiel usually has solid tail colouration, without tail stripes.

Author's note: Generally the male bird is the gender that has the brightest colouration. The male's colouration needs to be spectacular and vivid in most bird species because, very often, each male is competing with many other males for the right to mate with a female. Given that the female bird generally chooses the most attractive male, usually with the best calls and courtship 'dance' routines, to mate with (he is thought by her to be the most healthy animal with the best genetics to pass onto his offspring), the male bird needs to be very good-looking and athletic to attract her attention. The female bird does not usually need to be pretty herself in many of these cases because she will attract males regardless (she lays eggs and so the males need her, regardless of her appearance, if they are to have an opportunity to spread their genes onto the next generation). Also, the female benefits from being plainer because blander colours (dull colours, browns, greens and greys) will help her to hide from predators when she is vulnerable and sitting on eggs.

On some occasions, the usual situation is reversed and the female is the more colourful of the two sexes. This sometimes occurs in species where the females need to compete with each other for male mates (i.e. the reverse of the usual situation).

Some examples of bird species where the female is the 'prettier' bird:

- Painted Snipe

- Electus Parrot

- Plains Wanderer

- Cassowary

- Shining Flycatcher

- Red-backed Button-quail

- Painted Button-quail

Sexing birds picture 20

Sexing birds picture 20 - The female eclectus parrot is blue and red with a yellow eye. She is generally considered to be prettier than the male eclectus, who is bright green in colour.

Important facts and tips when sexing birds by colour:

- Know your species - read up about the bird species you are sexing so that you know which colour and pattern features you are looking for.

- Be aware of regional colour variations - some species of birds have colour variations (termed 'strains' or 'races') depending on what country you are in and also what region of a country you are in. In Australia, we may see colour variations in a bird species when going from northern Australia to southern Australia and/or from east to west. It is important to know what strain or race of a bird species you are dealing with first, before trying to determine the sex.

- Be aware of juvenile birds - pre-pubescent, immature, juvenile birds, regardless of sex, often look like females in colour. Young males generally do not get their bright male colouration until they have reached breeding age.

- Be aware of colour changes out of breeding season - some male birds (e.g. Ruff, Bar-tailed Godwit, Red-necked Phalarope) only get their full, sex-differentiated colouration during the breeding season. Out of season, they may look like females in appearance.

- Be aware of in-breeding and mutant strains - over-breeding and in-breeding and colour-selecting for abnormal colour variations in a bird species (e.g. cockatiels, budgerigars) can result in a loss of the normal colours and patterns, making it impossible for gender to be determined by physical means. For example, colour-diluted budgerigar strains often have atypical cere colours throughout life making it difficult to visually determine the males from the females. Similarly, atypically-coloured cockatiels often have ventral tail banding (stripes under the tail), even in the males, making this pattern-feature unreliable for sex-determination.

2d) Only female birds lay eggs.

2d) Only female birds lay eggs.

If one of your birds lays an egg, then it is a female. Simple. Only female birds lay eggs. Please note, however, that the absence of egg-laying in a bird does not, by-default, make it a male. Female birds fail to produce eggs for a variety of reasons, including: age (too young or too old), malnutrition, egg-binding, uterine disorders, ovarian disease, reproductive tract infections and various stressors.

Sexing birds images:

Sexing birds images: This yellow canary laid an egg in her cage. This makes her a female bird. The egg of a canary is a small, blue-grey egg.

2e) Behavioural differences between male and female birds.

2e) Behavioural differences between male and female birds.

Some bird species exhibit a degree of sexual dimorphism with regard to their behavioral characteristics. Obvious behavioural differences may exist between the sexes with such things as: nest-building, egg sitting, chick raising, preening and communal grooming, courtship rituals, food gathering, territory guarding, aggression, territorial singing, other forms of vocalisation and mating displays (e.g. dancing, sex attraction exhibitions). In the pet-ownership field, certain desirable traits like "talking" and "singing" are commonly ascribed to be better in one sex or the other by bird enthusiasts. Knowing which of the sexes commonly exhibits each behavior can provide a clue as to the sex of the bird in question.

Nest-building:

In nest-building species, knowing which of the two sexes commonly builds the nest can be useful to determining the sex of the bird, should a nest-building individual be spotted. Contrary to common belief, it is not always the female who builds the nest. In a great many species, both sexes actually build the nest together. In some cases, the work-load may be equal - the male and female birds both collecting the nest materials and working them into the nest. In other cases, the work-load may differ - the male might collect the nest materials, leaving the female to design and construct the nest itself. In a few species, it is actually the male who builds the nest alone (e.g. Satin Bowerbird): often as part of a courtship display to attract a female mate into his territory.

- Male bird nest building examples: Australian Brush-turkey (mound builder), Red-capped Plover, Cicadabird, Golden Bowerbird, Satin Bowerbird, Regent Bowerbird, Fawn-breasted Bowerbird, other Bowerbirds (note that male-constructed bowers are for display and mating purposes - after mating, the Bowerbird females leave to build their own egg-incubation nests).

- Female bird nest building examples: Mute Swan, Califormia Quail, Stubble Quail, King Quail, Superb Lyrebird, Albert's Lyrebird, Noisy Scrub-bird, Song Thrush, Rose Robin, most Robins, Crested Shrike-tit, Rufous Whistler, Eastern Whipbird, Superb Fairy-wren, most Fairy-wrens, most Emu-wrens, Grasswrens, White-browed Scrubwren, Weebill, Thornbills, Treecreepers, Friarbirds, Noisy Miner, Spinebills, Sunbirds, Olive-backed Oriole, Spangled Drongo, Golden Bowerbird, Satin Bowerbird, Regent Bowerbird, Fawn-breasted Bowerbird, other Bowerbirds, Green Catbirds, Riflebirds, Magpies, Currawongs.

- Paired nest building examples: Frigatebirds, Cormorants, Pelicans, Ospreys (the male collects the materials whilst the female works them into the nest), Pacific Baza, Goshawk, Wedge-tailed Eagle, Magpie Goose, Cape Barren Goose, Orange-footed Scrub Fowl, Masked Lapwing, Scaly-breasted Lorikeet, Tawny Frogmouth, Red-backed Kingfisher, Sacred Kingfisher, other Kingfishers, Rainbow Bee-eaters, Barn Swallow, Welcome Swallow, Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike, Trillers, Red-lored Whistler, Grey Shrike-thrush, Restless Flycatcher, Broad-billed Flycatcher, Leaden Flycatcher, Satin Flycatcher, Grey-crowned Babbler, Rufous Fantail, Willie Wagtail, Gerygones, Chats, Silvereyes, Tree Sparrow, Beautiful Firetail, other Firetails, Finches, Apostlebirds, Magpie-larks, Woodswallows, Australian Ravens.

Nest-sitting (egg incubation):

Knowing which of the two sexes commonly sits on the nest and incubates the eggs can be useful to know when determining the sex of a bird, should an egg-sitting individual be spotted. Contrary to common belief, it is not always the female who sits on the nest alone. In a few species, it is actually the male who sits on the nest alone and who is sometimes left to rear the chicks alone without the aid of the female. In a great many species, both sexes actually share the burden of egg incubation, the male and female birds alternating in the duty so that each can be regularly freed of the task to go and obtain some nutrition. The egg incubating work-load may be very even in some species - the male and female birds having equal spans of time on and off the nest. In other species, the female bird may bear the bulk of nest-sitting duties with the male only relieving her for short intervals.

Interesting note: In some species (e.g. Purple Swamphens), egg-sitting duties are not left solely to a single pair of birds (male and female). Some bird species live in vast family groups or harems (e.g. one or several males with many females) and many individual males and females may share the duty of sitting on the various clutches of eggs.

- Male bird egg incubation examples: Emu, Cassowary, Black Swan, Australian Brush-turkey (male tends the 'mound'), Mallee-fowl, Red-backed Button-quail, Painted Button-quail, Little Button-quail, Chestnut-backed Button-quail, other Button-quails.

- Female bird egg incubation examples: Chicken (Domestic Fowl), Swan, Osprey, Kite, Sparrowhawk, Little Eagle, Wedge-tailed Eagle, Black Swan, Freckled Duck, Cape Barren Goose, Shelducks, Maned Duck, Teal, most ducks, Quail, Common Peafowl, Lewin's Rail, Kori Bustard, Red-tailed Black-cockatoo, Glossy Black-cockatoo, Double-eyed Fig-parrot, Rainbow Lorikeet, Scaly-breasted Lorikeet, Musk Lorikeet, Eclectus Parrot, Australian King Parrot, Superb Parrot, Crimson Rosella, Green Rosella, Blue Bonnet, Mulga Parrot, Bourke's Parrot, Powerful Owl, most owls, Superb Lyrebird, Albert's Lyrebird, Noisy Scrub-bird, Skylark, Barn Swallow, Cicadabird, Song Thrush, Rose Robin, many Robins, Gilbert's Whistler, Black-faced Monarch, Eastern Whipbird, Grey-crowned Babbler, White-browed Babbler, Hall's Babbler, Golden-headed Cisticola, Superb Fairy-wren, most Fairy-wrens, most Emu-wrens, Grasswrens, White-browed Scrubwren, Hylacolas, Weebill, Thornbills, Treecreepers, Friarbirds, Noisy Miner, Spinebills, Sunbirds, House Sparrow, Olive-backed Oriole, Golden Bowerbird, Satin Bowerbird, Regent Bowerbird, Fawn-breasted Bowerbird, other Bowerbirds, Green Catbirds, Riflebirds, Magpies, Currawongs, Australian Ravens, Crows.

- Shared incubation examples: Diving-Petrel, Albatross, Petrel, Prions, Shearwaters, Storm-petrels, Rockhopper Penguin, Erect-crested Penguin, Little Penguin, Fiordland Penguin, Grebes, Tropicbirds, Frigatebirds, Cormorants, Darters, Pelican, Heron, Egrets, Jabiru, Ibis, Pacific Baza, Goshawk, Magpie Goose, Whistling-ducks, Swans, Buff-banded Rail, Crakes, Purple Swamphen (group sitting by many males and females), Dusky Moorhen (group sitting by many males and females), Native-hens (group sitting of many males and females), Brolga, Avocets, Dotterels, Cockatiel, Gang-gang Cockatoo, Galah, Tawny Frogmouth, most Nightjars, Red-backed Kingfisher, Sacred Kingfisher, Rainbow Bee-eaters, Pittas, Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike, Trillers, Crested Shrike-tit, Red-lored Whistler, Grey Shrike-thrush, White-eared Monarch, Pied Monarch, Satin Flycatcher, Broad-billed Flycatcher, Leaden Flycatcher, Rufous Fantail, Willie Wagtail, Gerygones, Chats, Silvereyes, Tree Sparrow, Beautiful Firetail, other Firetails, Finches, Mannikins, Starling, Figbirds, Spangled Drongo, Apostlebirds, Magpie-larks, Woodswallows.

Chick-rearing:

Knowing which of the two sexes commonly protects and feeds the chicks can be useful to know when determining the sex of a bird, should a chick-rearing individual be spotted. Contrary to common belief, it is not always the female who cares for and raises the chicks alone. In a few species, it is actually the male who is sometimes left to rear the chicks alone without the aid of the female. In a great many species, both sexes actually share the burden of chick rearing and protection. In some of these cases, the work-load may be equal - the male and female birds both feeding and escorting and protecting the chicks as a paired unit (e.g. geese, swans). In other cases, the nature of the care may differ - the male might guard the territory, keep a look-out for danger and collect the food for the female and chicks, leaving the female to guide and protect and warm the chicks more intimately. Some bird species even live in vast family groups or harems and many individual males and females may share the duty of feeding, teaching and protecting the chicks.

- Male bird chick rearing examples: Emu, Cassowary, Osprey (the male gathers food for the female and the chicks), Red-backed Button-quail, Painted Button-quail, Little Button-quail, Chestnut-backed Button-quail, other Button-quails, Plains-wanderer.

- Female bird chick rearing examples: Common Peafowl, Kori Bustard, Blue Bonnet (the female is fed by the male), Superb Lyrebird, Albert's Lyrebird, Noisy Scrub-bird, White-breasted Robin, Eastern Whipbird, Grey-crowned Babbler, White-browed Babbler, Golden-headed Cisticola, Superb Fairy-wren, most Fairy-wrens, most Emu-wrens, Grasswrens, Golden Bowerbird, Satin Bowerbird, Regent Bowerbird, Fawn-breasted Bowerbird, other Bowerbirds, Riflebirds.

- Shared chick rearing examples: Magpie, Albatross, Petrel, Rockhopper Penguin, Erect-crested Penguin, Tropicbirds, Frigatebirds, Cormorant, Darter, Gannet, Herons, Egrets, Jabiru, Ibis, Spoonbills, Pacific Baza, Kite (the male hunts and the female gives the food to the young), Goshawk (the male hunts and the female gives the food to the young), Little Eagle (the male hunts and the female gives the food to the young), Wedge-tailed Eagle (the male hunts and the female gives the food to the young), Whistling-ducks, Swans, Cape Barren Goose, Shelducks, Purple Swamphen (group sitting of many males and females), Dusky Moorhen (group sitting of many males and females), Oyster-catchers, Cockatiel, Red-winged Parrot, Tawny Frogmouth, Nightjars, Red-backed Kingfisher, Rainbow Bee-eaters, Skylark, Barn Swallow, Black-faced Cuckoo-shrike, Cicadabird, Trillers, Song Thrush, many Robins, Red-lored Whistler, Grey Shrike-thrush, Pied Monarch, Broad-billed Flycatcher, Leaden Flycatcher, Satin Flycatcher, Rufous Fantail, Willie Wagtail, Hylacolas, Weebill, Thornbills, Treecreepers, Friarbirds, many Honeyeaters, Chats, Sunbirds, Silvereyes, Tree Sparrow, Beautiful Firetail, other Firetails, Finches, Mannikins, Starling, Figbirds, Olive-backed Oriole, Spangled Drongo, Green Catbirds, Apostlebirds, Magpie-larks, Woodswallows, Magpies, Currawongs, Australian Ravens, Crows.

Aggression:

Male birds are generally more aggressive than females of the same species, however, in some of the large parrot species (e.g. Eclectus Parrots, Sulfur-crested Cockatoos), it will be the female who is the more aggressive. Female aggression is also encountered in a number of large ratite species like the Cassowary (female cassowaries are generally dominant over the males).

Courtship displays:

Usually the male bird displays prominently in courtship, using special stereotypic movements, mating dances, calls and other noises to attract a female mate or mates (some species are polygamous). Some species (e.g. Diving-Petrels) even have special courtship flying displays - special aerobatics designed to show off form, strength, stamina and agility to the prospective mate. In species where only the male bird displays (e.g. Feral Pigeons), witnessing a courtship display may make it easy for the observer to determine the sex of the bird in question.

In those few species where the female bird is the more vibrantly-coloured, the courtship roles might be reversed and the female bird might be the main courtier, instead of the male.

In many species, both sexes display courtship behaviour at the same time. This is commonly seen in water birds (e.g. swans), sea birds (e.g. herons, boobies, petrels, albatrosses, shearwaters) and in birds of prey (e.g. kites and ospreys), but many other species can and do show this complementary courtship. The male or males may perform a courtship display and the females may then vocalise and/or dance in response, using their courtship response to indicate their chosen mate or mates. In species where the female is the more vibrant gender, the female may initiate the courtship in the hope of gaining approval and a reply-dance by the male. If both sexes display, it might be very difficult to determine which of the 'dancers' is the male and which is the female.

Author's note: In those species where both sexes contribute to the courtship display, there might be specific actions or vocalisations in the shared display that are distinct to one sex or the other. Knowing which of the sexes shows a particular movement can make it possible for the very observant bird-watcher to tell the sexes apart. For example, although both male and female Rockhopper Penguins display and dance during their courtship, the male has a specific head-shaking action that is very unique to his sex. Similarly, the male Australasian Gannet nape-bites the female during courtship (she does not bite him).

Vocalisations and bird-calls:

Usually the male bird is the most vocal of the two sexes, using special calls, chirps, whistles and squawks to communicate everything from a desire to mate to the aggressive proclamation of territory. In species where only the male bird calls, witnessing a singing display may make it easy for the observer to determine the sex of the bird in question.

In those few species where the female bird is the more vibrantly-coloured (e.g. Button-quails), the roles might be reversed and the female bird might be the main caller, instead of the male. In such cases, the female bird will sing to announce her intent to breed and to mark out her territory.

Sometimes both genders will vocalise. If both genders sound the same, it might well be impossible for the casual bird observer to be able to determine the sex of the singer. On other occasions, however, both sexes may sing, but their calls may sound very different. An intimate knowledge of the variations that exist in bird song between the two sexes may enable an astute observer to determine the gender of the avian singer. Even more subtly, one of the genders may only start the call, leaving the other gender to finish it off. Knowing which of the genders starts and finishes may also make it possible to tell the sexes apart.

Cautions when using behaviour to sex birds: Obviously, using behaviour as a guide to determining avian gender is not an all-or-nothing thing. There can be much cross-over between the sexes with regard to certain behaviors and behaviors that are commonly attributed to just one of the sexes may well crop up in the other sex from time to time. For example, "talking ability" is said to be more common and well-developed in male Psittacines (and other "talking" species), yet there are female birds out there who can and do talk very well. Aggression too can be variable from bird to bird, depending on the animal's past experiences, even if one sex is said to be more aggressive than another.

The pairing-off of birds, similarly, does not follow set rules. Knowing that one bird in a pair is male does not necessarily make the other bird, by default, a female. Homosexual pairing and even same-sex copulation (males with males and females with females) does occur in the bird world. Some bird species even exist in vast polygamous families, with some males having many females and some females having many males. The outcast, pre-pubescent young males of certain bird species (e.g. Cockatoos) will sometimes flock together in huge 'bachelor groups' where pairing and communal grooming activities will be quite normal.

2f) Vent-sexing in avian species that have a phallus (penis).

2f) Vent-sexing in avian species that have a phallus (penis).

The males of certain species of birds have a copulatory penis-type organ called a phallus. Orders of birds in which such a copulatory organ is found include the Orders: Anseriformes (ducks, geese, swans, screamers), Galliformes (mallee fowls, chickens, guinea fowl, grouse, quails, pheasants, turkeys, peafowls) and Struthioniformes or "ratites" (emus, cassowaries, ostriches, rheas, kiwis). Birds of the Anseriformes Order have a cork-screw-like penis which unwinds from the cloaca as the bird mates or is stimulated for artificial insemination. Birds of the Galliformes Order have a less-defined copulatory organ that is essentially comprised of some flabby folds of tissue located deep within the cloacal space.

Experienced bird handlers can visualise the phallic organs of male birds of these Orders by slightly everting the cloacas (vents) of such birds. The bird is rested on its back (hard with large ratites) and the cloaca is everted by pressing downwards on the cranial and caudal aspects of the vent. The inner lining of the cloaca should "roll outwards" with this firm, outwards-directed pressure and, if done correctly (and if the bird is a male, of course), the penis will appear on the lower left-hand-side of the cloaca.

IMPORTANT - DO NOT attempt to vent sex baby birds, especially newly-hatched birds or day-old chickens. If done incorrectly, vent-sexing can result in the injury and/or death of newly-hatched birds.

Bird sexing images

Bird sexing images - Ducks, geese and swans are members of the Anseriformes Order of birds. The males of these species have a penis organ hidden inside of their cloaca.

3. Feather sexing chickens.

3. Feather sexing chickens.

The genes that determine whether or not a newborn chicken grows its primary feathers (main flight feathers) rapidly or slowly are found on the sex chromosomes of the bird's genome (DNA). These sex chromosomes are the same chromosomes that are responsible for determining the sex or gender of the bird in question. A bird with ZZ sex chromosomes is male. A bird with ZW sex chromosomes is female.

Because the genes for "rapid-feathering" and "slow-feathering" are found on the sex chromosomes, these feathering genes or 'traits' are said to be "sex-linked".

Commercial chickens are genetically selected and bred such that all newborn female chickens will inherit the recessive, sex-linked gene for "rapid feathering" and all newborn male chickens will inherit the dominant, sex-linked gene for "slow feathering." The purpose of this breeding is to ensure that newborn chickens, straight out of the egg, can be sexed easily by the differences in the lengths of the primary feathers of each of the sexes. Because of their "rapid-feathering" sex-linked genes, newly-hatched female chickens are "born" with longer primary feathers than their "slow-feathering" male counterparts. The female hatchlings' primary feathers are longer than their covert feathers (the next row of feathers on the wing), which is different to the situation seen in the male hatchlings, whose covert feathers are as long as or even longer than their primaries.

The link below has excellent photos showing the differences in feather length that exist between male and female chicken hatchlings:

http://animalsciences.missouri.edu/reprod/ReproTech/Feathersex/index.htm

4a. DNA bird sexing (avian DNA sexing) - bird feather sexing, blood sexing and eggshell sexing.

4a. DNA bird sexing (avian DNA sexing) - bird feather sexing, blood sexing and eggshell sexing.

The body features and behavioral features mentioned so far, which can be used to determine the sex of many bird species, may not be all that useful in determining the sexes of juvenile birds or bird species that are without obvious sexual dimorphism. If bird sexing needs to be performed on juvenile animals, non-breeding animals (e.g. off-season birds) or avian species without obvious sexual dimorphism, then more complicated, invasive methods of bird sexing may be required. One of these is DNA bird sexing (avian DNA sexing).

In DNA sexing, a fresh sample of the bird's blood or another body tissue (e.g. feathers or eggshells), which contains the nucleated cells of the bird and, therefore, by default, the entire blueprint of the bird's genetic DNA make-up, is sent to a genetics laboratory for sex determination. At the laboratory, the DNA from the bird cells is extracted and amplified (i.e. multiplied using a special technique called PCR) and combined with special, breed-specific, sex-specific DNA markers that are designed to detect whether the bird DNA in the sample contains ZZ sex chromosomes (i.e. the DNA is male) or ZW sex chromosomes (i.e. the DNA is female). The DNA sexing result is then sent back to the bird's vet or directly to the bird's owner.

Most genetics labs these days have the capacity to determine the sex of a broad range of avian species and types. The link below shows the list of bird species that are able to be sex-tested by one of the companies providing this DNA sexing service. This list of testable breeds is by no means exhaustive and is probably increasing by the day so shop around.

http://www.avianbiotech.com/SpeciesList.asp

Any body tissue that contains DNA can be used to sex birds, however, in order to make the sexing process as minimally invasive and low-stress for the bird as possible and as simple-to-perform as possible for the vet or bird owner, most labs can now perform the DNA sexing procedure on samples of feathers, blood and eggshells (the shells discarded by day-old-chicks during the hatching process), which are easily obtained. Most labs will even send special sample collection kits out directly to bird owners, so that they can collect the DNA-containing samples themselves at home. At the end of this page, I have included some links to genetics companies who provide this do-it-yourself mail service.

Some points about DNA feather sexing:

- The DNA testing is performed on feathers plucked freshly from the bird.

- The DNA to be tested comes from the region of the feather shaft located underneath the bird's skin.

- Fallen or molted feathers are not to be used. They must be freshly plucked.

- Blood feathers will work okay, but are not necessary. Mature feathers will work just as well.

- If used, blood feathers should be allowed to dry before being placed into the lab sample bag.

- Feather sexing is safer and less-stressful to perform than blood-sample DNA sexing.

- Different genetics labs have different feather submission rules (e.g. length of feathers needed, number of feathers needed, place on the body where the feathers must be plucked from and so on) so you need to read the instructions carefully before pulling any feathers out and submitting them.

- Feather sexing is thought to be as accurate as blood DNA sexing.

Some points about DNA blood sexing:

- Blood sexing is less safe and more stressful to perform than DNA feather sexing.

- Blood sexing is thought to be no more accurate than DNA feather sexing.

- Only 1-2 drops of blood are needed in order to perform DNA blood sexing.

- Blood can be obtained from veins in the neck, wings and legs of the bird, but such venepuncture is stressful and tricky to perform on the healthy, struggling bird and can result in excessive blood loss (dangerous in small birds).

- Clipping the end of a toenail slightly short such that 1-2 drops of blood are obtained usually works fine and is the safest bleeding method for the bird. After collecting the sample, make sure to blot the bleeding nail with a tissue or soap-bar and ensure that the bleeding has stopped before releasing the bird.

- Most labs provide a do-it-yourself blood sample paper (blood card) for collecting the blood sample. The bird's blood is blotted onto the appropriate section of the card, air-dried and then packed into the sample kit for sending back to the lab.

- If using nail clippers to clip the bird's claws and collect the blood, ensure

that the nail clippers used are washed thoroughly (boiling water) between birds, if more than one bird

is being sampled. This will prevent the transmission of blood-borne diseases from bird to bird

and it will also prevent contamination of the samples with the blood from other birds (which could lead to an

erroneous lab result).

Some points about DNA egg-shell sexing:

- Freshly-cracked eggshells contain cells and DNA from the newly-hatched chick. These

cells can be used to determine the sex of the bird chick that emerged from the shell in question.

- The eggshells need to be fresh.

- The eggshells to be tested should not have been contaminated by other hatching chicks and eggshells.

It is no good if blood-or-membrane-covered shells have become all mixed together (contaminating one another with DNA)

or if they have had a number of slimy, DNA-covered chicks crawling all over them.

- Eggshell sex determination is particularly useful in bird breeding colonies.

- Eggshell sex determination is much less stressful than blood or feather sexing.

- Eggshell sex determination can be used to determine the sex of avian chicks from only a few hours old.

- Eggshell sex determination of chicks does not run as much risk of disturbing the mother bird.

- Most labs provide a do-it-yourself sample kit for collecting the egg shell samples. The shells are collected, labeled, air-dried and then packed into the sample kit for sending back to the lab.

IMPORTANT: Sending feather, blood and/or egg-shell samples or any other avian biological samples overseas or inter-state by post (even if in a suitable sample collection package) may be illegal. Many states and countries forbid the sending of biological materials by post because of the risk of exotic disease transmission (e.g. avian flu) to postal workers and other avian species. Where possible, you should elect to use the services of a bird-sexing genetics company in your own country and/or state and, even then, you should contact the gene company and your local postal service to be sure that it is legal for you to send such samples through the mail.

4b. Endoscopic bird sexing.

Before the advent of DNA sexing, many species of birds (particularly juvenile birds and birds without obvious physical male-versus-female differences) could only be reliably sexed using endoscopy. Known as surgical sexing, endoscopic bird sexing required the bird to be placed under an anaesthetic so that an endoscope (basically, a long, thin rod with fibre-optic imaging equipment set into the shaft to allow visualisation of the bird's internal organ structures) could be inserted through the skin and into the abdominal airsacs of the bird. Part of the bird's unique respiratory system, the airsacs of a bird are basically large chambers of air with see-through, ultra-thin, membranous walls. When the endoscope is inserted into the abdominal airsacs of the bird, the bird's entire abdominal cavity, including the reproductive organs, is visible through the airsac's see-through, membranous wall. The vet performing the endoscopic sexing can determine whether the bird is male or female based upon the appearance and number of the reproductive organs. Males have two internal testicles and females have only a single internal ovary.

Because it is much more invasive and risky than DNA feather sexing and other forms of DNA bird sexing, endoscopic sexing is likely to become much less common for purposes of avian gender determination than it has been. This trend away from invasive endoscopy will only continue as the DNA sexing tests become more and more readily available and cost-effective and cover more and more species of birds. Endoscopic bird sexing is most likely to be used in situations where DNA testing is unavailable; in species that have no DNA sexing test available to them and in multiple-bird, constricted-finance situations (e.g. wildlife groups, high-output breeding facilities and zoos) where the cost of mass DNA testing might actually end up more expensive than having an endoscope on-site.

Pros (advantages) of endoscopic bird sexing:

- In the hands of a skilled operator, surgical sexing is quick to perform.

- The endoscope procedure allows other internal organs to be viewed and examined.

- With experience, surgical sexing is quite accurate to perform.

- The examination is not dependant upon the bird being sexually mature.

- It allows bird species with no DNA sexing test available, to be sexed.

- In experienced hands, the vet can also get some idea of what stage the female bird is at with regard to her sexual maturity and her stage of the breeding cycle.

Cons (disadvantages) of endoscopic bird sexing:

- An anaesthetic is needed, which might be of risk to the bird.

- There is some risk of peritonitis (infection of the internal abdominal cavity) and airsacculitis (infection of the air sacs) with this procedure if aseptic procedure is not followed.

- A fair bit of relatively costly equipment is needed.

- The procedure is more stressful and invasive than DNA sexing.

- There is a greater chance of hemorrhage, which can be risky in small birds.

- There is a greater risk of trauma to the internal organs, which can be risky.

- There is a greater risk of rib fractures.

- It can be difficult to visualize the gonads (and therefore the sex) of fat birds.

- Endoscopic sexing needs an experienced operator to get the best result.

- It can only be done by a vet or other person licensed to anesthetize and perform surgery on birds.

- For operators, there is the risk of infectious disease organisms (e.g. Chlamydia) infecting the operator.

- On an individual basis, endoscopy is potentially more costly to owners than DNA sexing.

Your Bird Sexing Links.

To go from this avian sexing page to our homepage, click here.

To go from this avian sexing page to our homepage, click here.

To go from this avian sexing page to our animal sexing topics list, click here.

http://www.budgies.org/info/faq.html

A nice general FAQ sheet on budgies. Includes info on sexing parakeets.

http://www.budgieplace.com/index.html

An awesome budgie and parakeet site. Has good parakeet sexing and feather-colour sections and lots of pictures.

http://animalsciences.missouri.edu/reprod/ReproTech/Feathersex/index.htm

A neat pictorial resource on feather sexing chickens.

Some companies that provide DNA bird sexing services (not exhaustive - there are many others):

http://www.dnasolutions.com.au/dna-sexing.htm

http://www.saturnbiotech.com.au/serv-birdsex.html

http://www.dnanow.com/dna-bird-tests.htm - US company.

http://www.healthgene.com/avian/dna_sexing.asp

http://www.avianbiotech.com/SexingCenter.htm

http://www.avianbiotech.com/questionsaboutfeathersexing.htm

http://www.avianbiotech.com/SpeciesList.asp

Bird Sexing References and Suggested Readings.

1) Raidal SR, Anaesthesia, Fluid Therapy and Surgery. In Raidal SR: Avian Medicine, Perth, 2001, Murdoch University.

2) Birds of Australia. In Reader's Digest Complete Book of Australian Birds,

Surry Hills, 2002, Reader's Digest Pty Ltd.

Copyright August 7, 2010, Dr. O'Meara BVSc (Hon), www.pet-informed-veterinary-advice-online.com.

All rights reserved, protected under Australian copyright. No images or graphics on this Pet Informed website may be used without written permission of their owner, Dr. O'Meara.

Please do not steal our images: a lot of time and effort goes into getting these pictures

so that people can view them on our site.

Important disclaimer: Please note that this author and website is in no way affiliated with any of the genetics companies or information websites that were listed or linked-to on this page. Pet Informed's reasons for mentioning these companies and websites

is so that readers interested in reading more about bird sexing or obtaining avian sexing DNA services

will know where else to turn. Pet Informed receives no commercial or reputational benefit from any of these companies or websites for mentioning them and can not make any guarantees or claims, either positive or negative, about these websites' information accuracy, products, customer service practices or business practices.

Choosing to access DNA bird sexing services from any company on the web is your decision alone and Pet Informed can not and will not take any responsibility for any death, damage, injury or loss of reputation and business

that occurs should you choose to take this sex-determination path with your bird. Do your homework and research all such bird sexing products carefully before spending your money and risking your pet's health on any such products.

|

Examples of bird species where the male and female birds differ in beak length or shape:

Examples of bird species where the male and female birds differ in beak length or shape:

In nest-building species, knowing which of the two sexes commonly builds the nest can be useful to determining the sex of the bird, should a nest-building individual be spotted. Contrary to common belief, it is not always the female who builds the nest. In a great many species, both sexes actually build the nest together. In some cases, the work-load may be equal - the male and female birds both collecting the nest materials and working them into the nest. In other cases, the work-load may differ - the male might collect the nest materials, leaving the female to design and construct the nest itself. In a few species, it is actually the male who builds the nest alone (e.g. Satin Bowerbird): often as part of a courtship display to attract a female mate into his territory.

In nest-building species, knowing which of the two sexes commonly builds the nest can be useful to determining the sex of the bird, should a nest-building individual be spotted. Contrary to common belief, it is not always the female who builds the nest. In a great many species, both sexes actually build the nest together. In some cases, the work-load may be equal - the male and female birds both collecting the nest materials and working them into the nest. In other cases, the work-load may differ - the male might collect the nest materials, leaving the female to design and construct the nest itself. In a few species, it is actually the male who builds the nest alone (e.g. Satin Bowerbird): often as part of a courtship display to attract a female mate into his territory. Usually the male bird displays prominently in courtship, using special stereotypic movements, mating dances, calls and other noises to attract a female mate or mates (some species are polygamous). Some species (e.g. Diving-Petrels) even have special courtship flying displays - special aerobatics designed to show off form, strength, stamina and agility to the prospective mate. In species where only the male bird displays (e.g. Feral Pigeons), witnessing a courtship display may make it easy for the observer to determine the sex of the bird in question.

Usually the male bird displays prominently in courtship, using special stereotypic movements, mating dances, calls and other noises to attract a female mate or mates (some species are polygamous). Some species (e.g. Diving-Petrels) even have special courtship flying displays - special aerobatics designed to show off form, strength, stamina and agility to the prospective mate. In species where only the male bird displays (e.g. Feral Pigeons), witnessing a courtship display may make it easy for the observer to determine the sex of the bird in question.

The body features and behavioral features mentioned so far, which can be used to determine the sex of many bird species, may not be all that useful in determining the sexes of juvenile birds or bird species that are without obvious sexual dimorphism. If bird sexing needs to be performed on juvenile animals, non-breeding animals (e.g. off-season birds) or avian species without obvious sexual dimorphism, then more complicated, invasive methods of bird sexing may be required. One of these is DNA bird sexing (avian DNA sexing).

The body features and behavioral features mentioned so far, which can be used to determine the sex of many bird species, may not be all that useful in determining the sexes of juvenile birds or bird species that are without obvious sexual dimorphism. If bird sexing needs to be performed on juvenile animals, non-breeding animals (e.g. off-season birds) or avian species without obvious sexual dimorphism, then more complicated, invasive methods of bird sexing may be required. One of these is DNA bird sexing (avian DNA sexing).  Many owners of birds (particularly poultry and parrot species) find it very difficult to determine the gender or sex of their avian pets and often need their veterinarian or their local bird-breeder to sex their birds for them.

Many owners of birds (particularly poultry and parrot species) find it very difficult to determine the gender or sex of their avian pets and often need their veterinarian or their local bird-breeder to sex their birds for them.  Before you handle and assess the sex of any bird, read up about the species you are dealing with first. Knowing what you are looking for beforehand, gender-wise and age-wise, will help you to determine the bird's sex more quickly, resulting in minimal handling and stress for the animal concerned. Also, some species of birds pose certain risks to the handler during handling, which are useful to know before you attempt to grab hold of the animal.

Before you handle and assess the sex of any bird, read up about the species you are dealing with first. Knowing what you are looking for beforehand, gender-wise and age-wise, will help you to determine the bird's sex more quickly, resulting in minimal handling and stress for the animal concerned. Also, some species of birds pose certain risks to the handler during handling, which are useful to know before you attempt to grab hold of the animal.